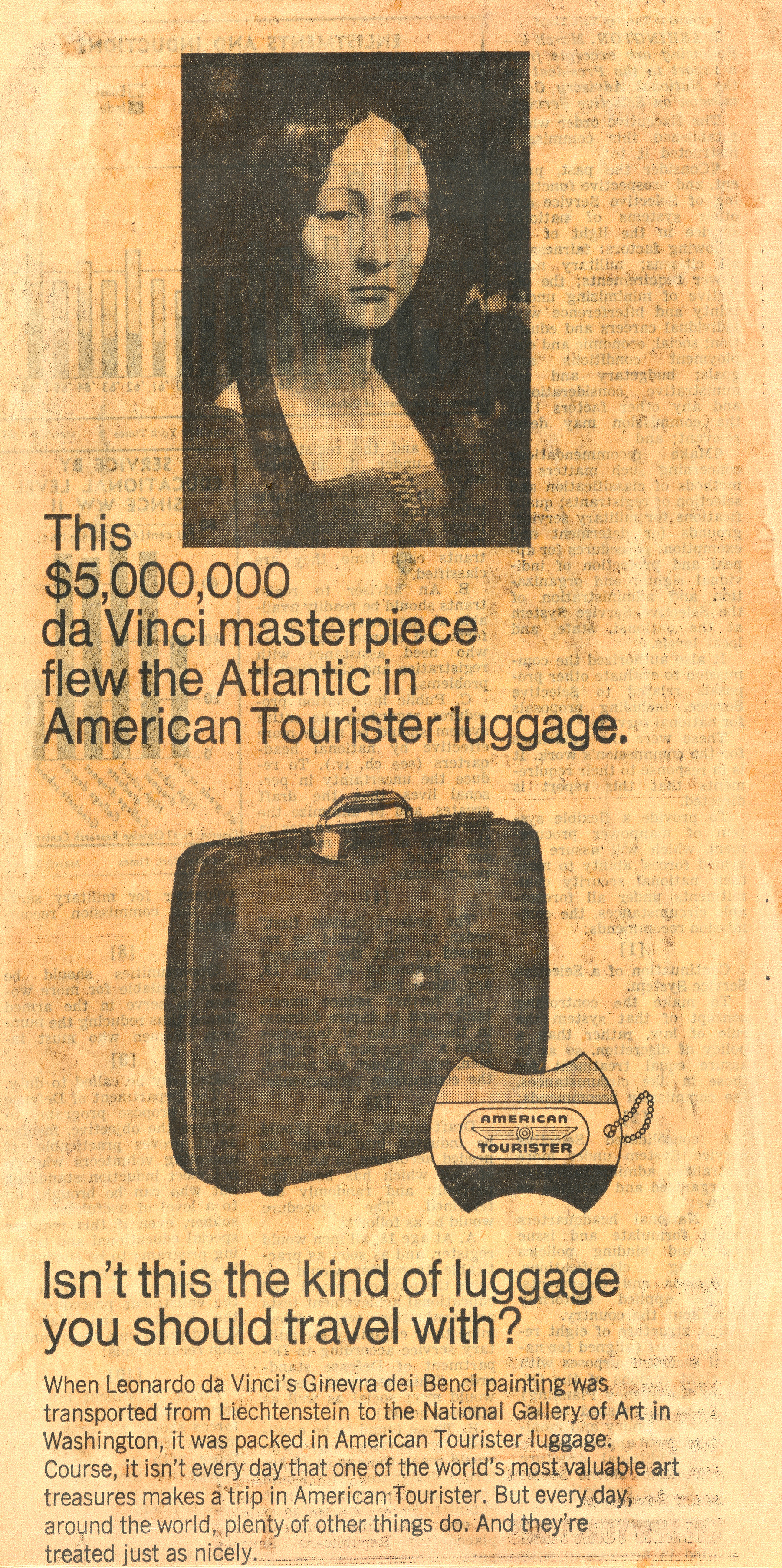

1. Leonardo painted Ginevra de’ Benci before the Mona Lisa

Leonardo painted Ginevra de’ Benci when he was in his early twenties, around 1474 to 1478. He would paint the Mona Lisa some 30 years later.

Without the experiments and innovations Leonardo made while painting Ginevra, the Mona Lisa might have looked very different.