Introducing an impetuous artist—and his studio

Although Johannes Vermeer is one of the most significant artists of the 17th century, much of the Dutch painter’s life and practice have remained a mystery. Until now.

The National Gallery has four paintings traditionally attributed to Vermeer. In 2020 and 2021, conservators, curators, and scientists took them into the conservation lab and used technical imaging to map the mineral elements in the artist’s pigments.

Seeing things hidden to the naked eye, they made some surprising new discoveries about Vermeer and his process.

Only about 35 paintings in the world are attributed to Vermeer. Now there is one fewer.

For nearly 50 years, scholars have questioned whether Vermeer actually painted Girl with a Flute. It was once thought to be a companion piece to Girl with the Red Hat because of their compositional similarities, nearly identical size, and similar wood panel supports. But the blocky brushwork and awkwardly positioned figure in Girl with a Flute have led many to doubt that the same artist painted both.

Over the last two years, National Gallery curators, conservators, and scientists have worked together to resolve this uncertainty. The team concluded that the artist who created Girl with a Flute was likely a studio associate of Vermeer’s—someone who understood the Dutch artist’s process but was unable to master it.

The artist who painted Girl with a Flute did not have the precision or control we see in Vermeer’s Girl with the Red Hat. But analysis of the two paintings shows that they both use some of the same distinctive pigments, which suggests that they might have been made in the same studio.

Vermeer had a studio.

Until now, most scholars had never considered that Vermeer might have had pupils or studio assistants. Yet new technical evidence suggests just that.

Microanalysis of paint samples from Girl with a Flute and Girl with the Red Hat reveals striking similarities. In both paintings, we find green earth in the shadows on the women’s faces. Using this pigment for flesh-tone shadows was highly unusual in Dutch paintings—we haven’t seen it in works by any of Vermeer’s exact contemporaries.

The mystery artist who painted Girl with a Flute was familiar with Vermeer’s unique methods and materials, but unable to achieve his level of expertise. They may have been a pupil or apprentice in training, an amateur who paid Vermeer for lessons, a freelance painter hired on a project-by-project basis, or even a member of Vermeer’s family.

This exciting notion of a studio calls into question the long-held idea of Vermeer as a lone genius. On the contrary, he might have been a mentor and educator, training a future generation of artists.

Vermeer was more spontaneous than we thought.

Looking beneath the polished, controlled surfaces of his paintings reveals that he wasn’t always a painstakingly slow perfectionist. At times, we see an impetuous, even impatient artist.

For example, microscopic analysis of the paint layers beneath the surface of Woman Holding a Balance reveals that Vermeer began with a monochrome painted sketch. As we know from chemical imaging, he then quickly applied a bold underlayer to plot out forms, colors, and patterns of light.

Further imaging suggests that Vermeer added a copper-containing material to speed the drying of the black pigment so that he could proceed to the painting’s final stages.

Slide the bar to view chemical image

Vermeer sometimes painted over other paintings.

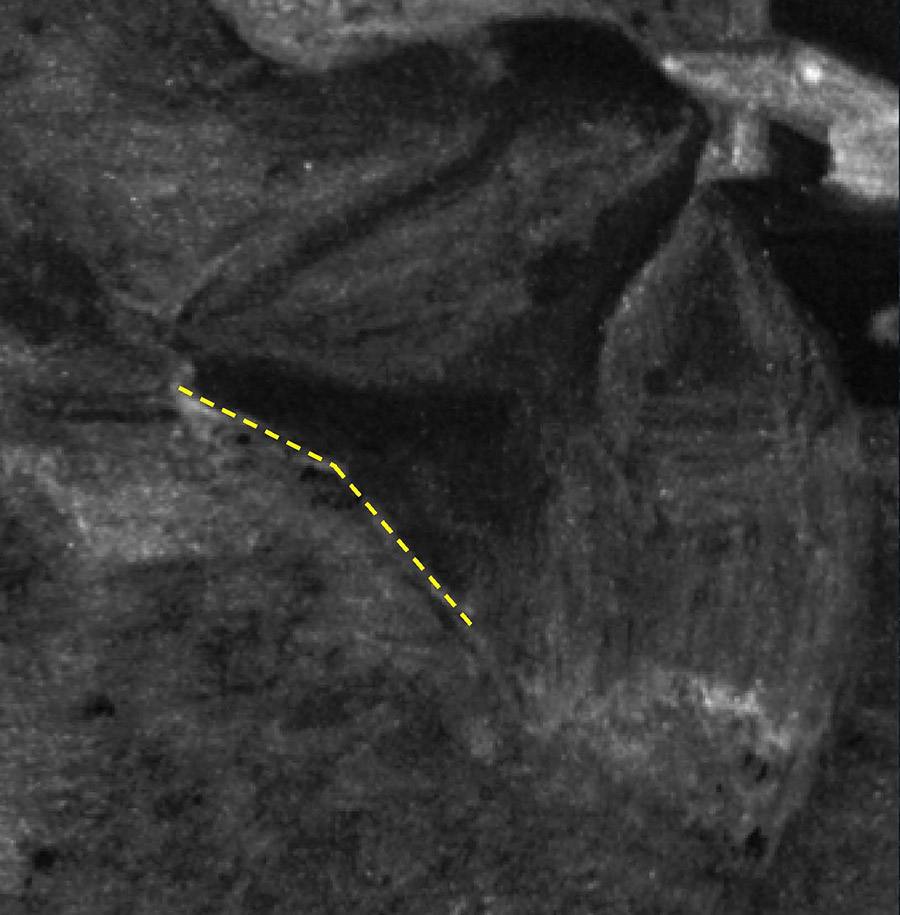

In the early 1970s, curators, conservators, and scientists learned from an X-ray image that Vermeer painted Girl with the Red Hat over a partially completed portrait of a man in a black hat, possibly painted by another artist.

Rather than scraping away the image or applying a covering layer, Vermeer rotated the panel 180 degrees and then painted directly over the portrait.

Over the last 20 years, advances in chemical imaging and image processing methods have allowed us to see the man in greater detail than ever before. In the absence of written records, these noninvasive techniques offer curators and scholars a glimpse at how Vermeer worked and clues about the people he depicted. One day, we may even be able to identify the black-hatted man—or the artist who painted him.

This digitally processed image shows the lead-containing pigments in the layer underneath the painting of Girl with the Red Hat.

Vermeer built up colors in mixtures, layers, and careful contrasts. He sometimes used several pigments of the same color.

-

Looking closely at A Lady Writing reveals how Vermeer manipulated his materials and technique to achieve surface effects.

(Keep scrolling to learn more.)/

-

A close-up view of the woman’s yellow jacket sleeve reveals Vermeer’s thoughtful use of fluid paints. Individual brushstrokes and dotted highlights spread and settled as they dried, creating a smooth surface.

(Keep scrolling.)/

-

In this microscopic close-up, arrows point to cool taupe and pale yellow pigments applied in soft dotted strokes. By setting these fluid touches of paint together, Vermeer created subtle effects of light and shadow.

/

Analysis of microscopic paint samples and maps obtained through imaging show that Vermeer used four different yellow pigments: two types of lead-tin yellow, yellow ochre, and likely yellow lake. The result is a rich, complex yellow, which Vermeer deliberately and thoughtfully composed.

Sometimes Vermeer changed his mind.

Technical imaging now allows us to visualize the artist’s working process more clearly and identify subtle changes.

Looking at A Lady Writing using infrared reflectance imaging spectroscopy—a technique that helps visually separate the pigments in a painting—reveals that Vermeer first painted the quill pen in a more vertical position to suggest active writing.

Using the same imaging, we see that, in the initial design for Woman Holding a Balance, Vermeer painted the scale at an angle. He later positioned it parallel to the picture plane, the two pans in perfect equilibrium.

Johannes Vermeer, Woman Holding a Balance, c. 1664, oil on canvas, Widener Collection, 1942.9.97

Slide the bar to view chemical image

Misattributions are one thing. Fakes are another.

In the 1930s, during a climate of “Vermeer fever,” Andrew W. Mellon purchased two paintings—The Lacemaker and The Smiling Girl—that became part of the National Gallery’s collection in 1937.

Imitator of Johannes Vermeer, The Lacemaker, c. 1925, oil on canvas, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.54

Imitator of Johannes Vermeer, The Smiling Girl, c. 1925, oil on canvas, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.55

Almost as soon as the paintings arrived, critics doubted their authenticity. The stiff, awkward figures; clumsy brushwork; and lack of attention to anatomical proportions were inconsistent with Vermeer’s work.

Our recent pigment analysis confirms that these suspicions were correct. It reveals the presence of synthetic ultramarine, a pigment that became available only in the 19th century, and lead chromate, a yellow pigment first produced in 1811.

The presumed forger, Theodorus van Wijngaarden, was born in 1874 (200 years after Vermeer’s death). He “aged” his paintings by drying them in the sun to expedite cracking; pressing the canvases against a beach ball; and tinting them to imitate the look of old, discolored varnish.

While we are missing many details about Vermeer’s life, the things we do know helps us understand this artist and his extraordinary works.

Explore related stories

Art in your inbox

Our weekly email features news, events, exhibitions, and more.