Mounting

Sarah Greenough

When Georgia O’Keeffe assembled the Key Set of Alfred Stieglitz’s work after his death in 1946, she considered for inclusion only the mounted photographs in his possession—because she knew that Stieglitz did not consider a work finished until it had been mounted. She also stipulated that his mounts should remain unchanged. Although Stieglitz used vertical mounts for both horizontal and vertical photographs throughout his career, his choice of materials—the size, color, and texture of the mount board and window mat—and his treatment of the photograph itself varied considerably throughout his life.

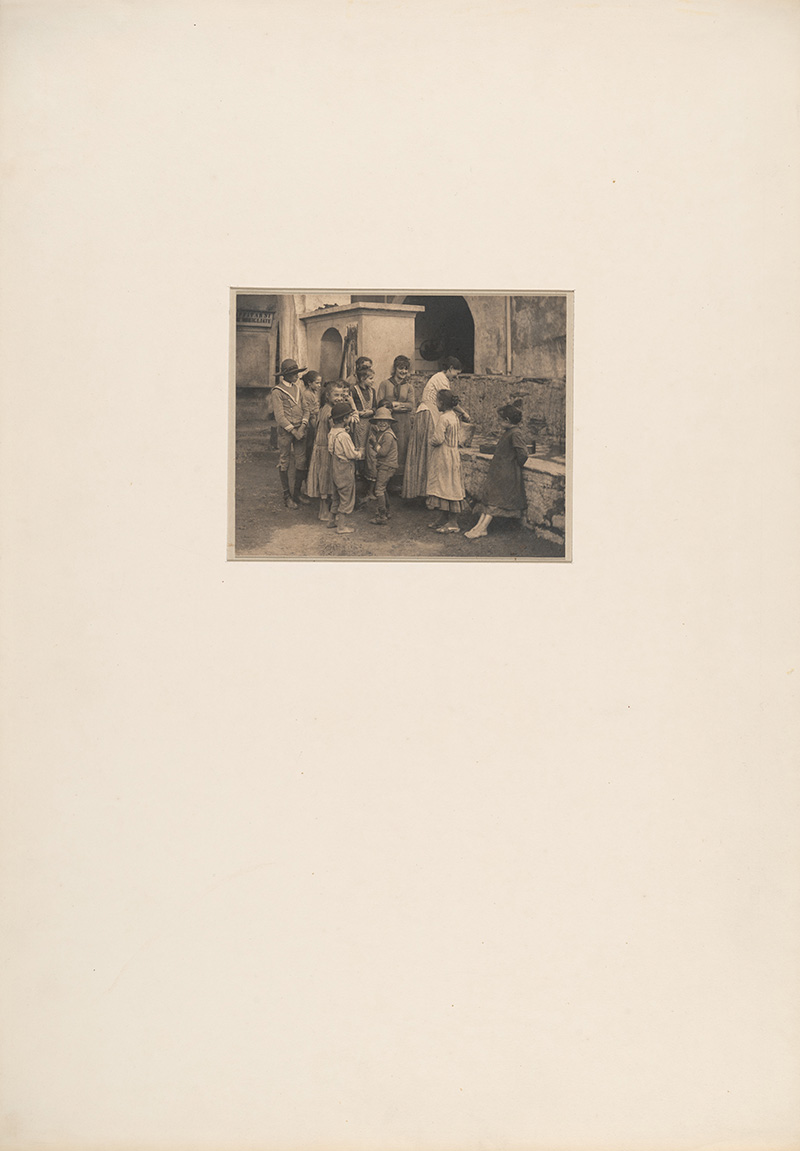

Alfred Stieglitz, The Last Joke—Bellagio or A Good Joke, 1887, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.30

Key Set number 33

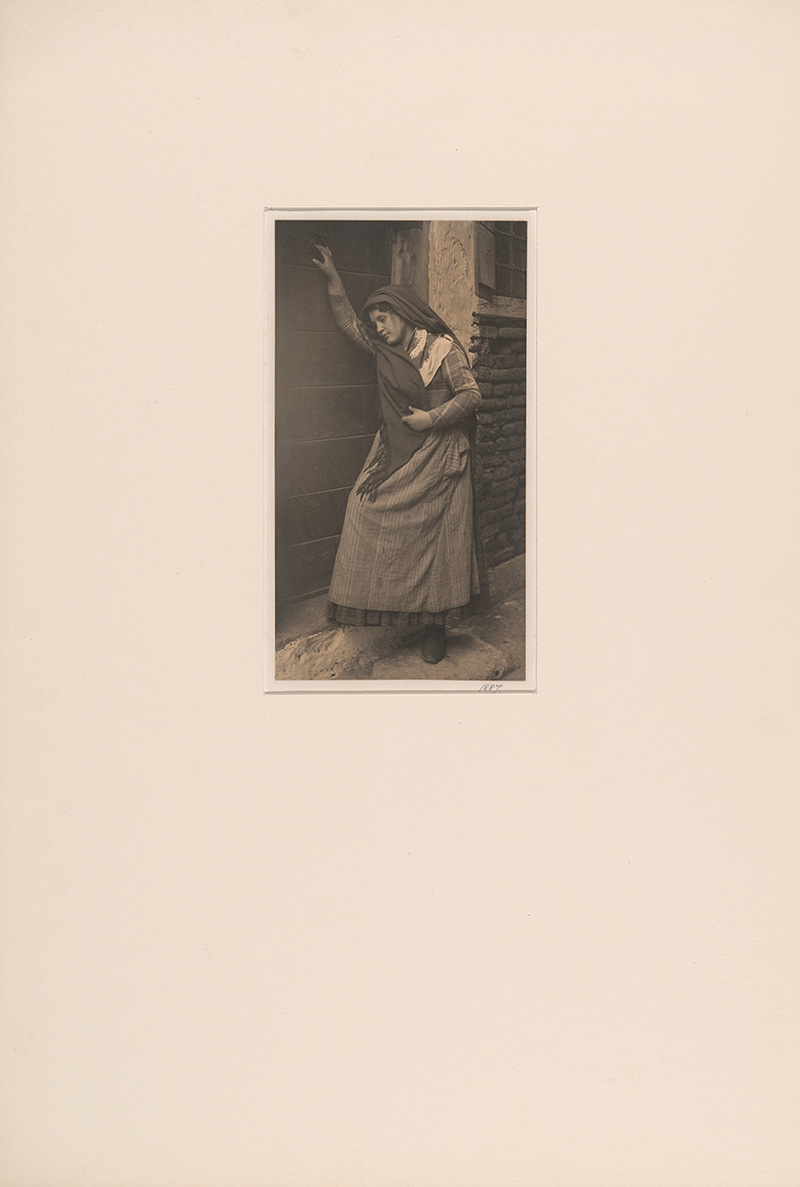

Alfred Stieglitz, The Wanderer’s Return, 1887, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.36

Key Set number 42

During the 1880s, Stieglitz most often trimmed a print to the edge of the image and placed it on a cream board that was significantly larger than the print itself (often three times its height and width). After attaching the print to the board, he covered it with a cream, single-ply window mat, leaving a space of about 1/4 inch around the print. For vertical prints, he often left twice as much space at the bottom of the board than at the top; for horizontal prints, he usually left two-and-one-half times as much space at the bottom of the board than at the top.

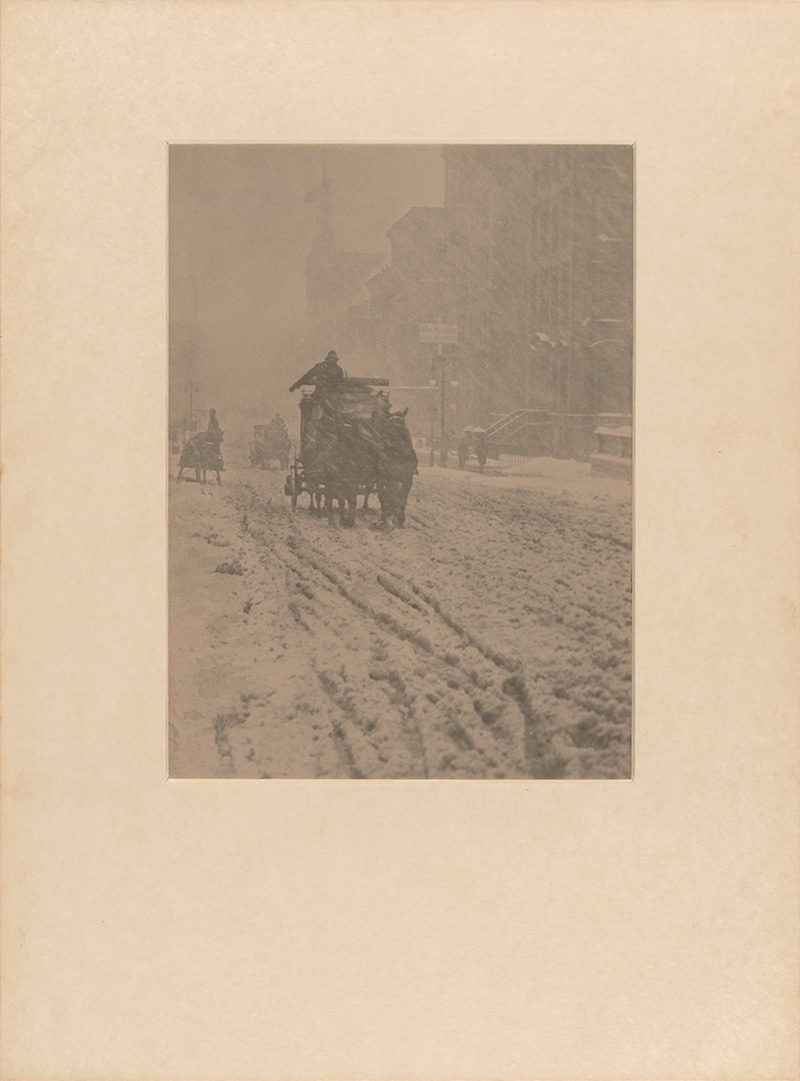

Alfred Stieglitz, Winter—Fifth Avenue, 1893, printed 1897 or later, carbon print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.94

Key Set number 84

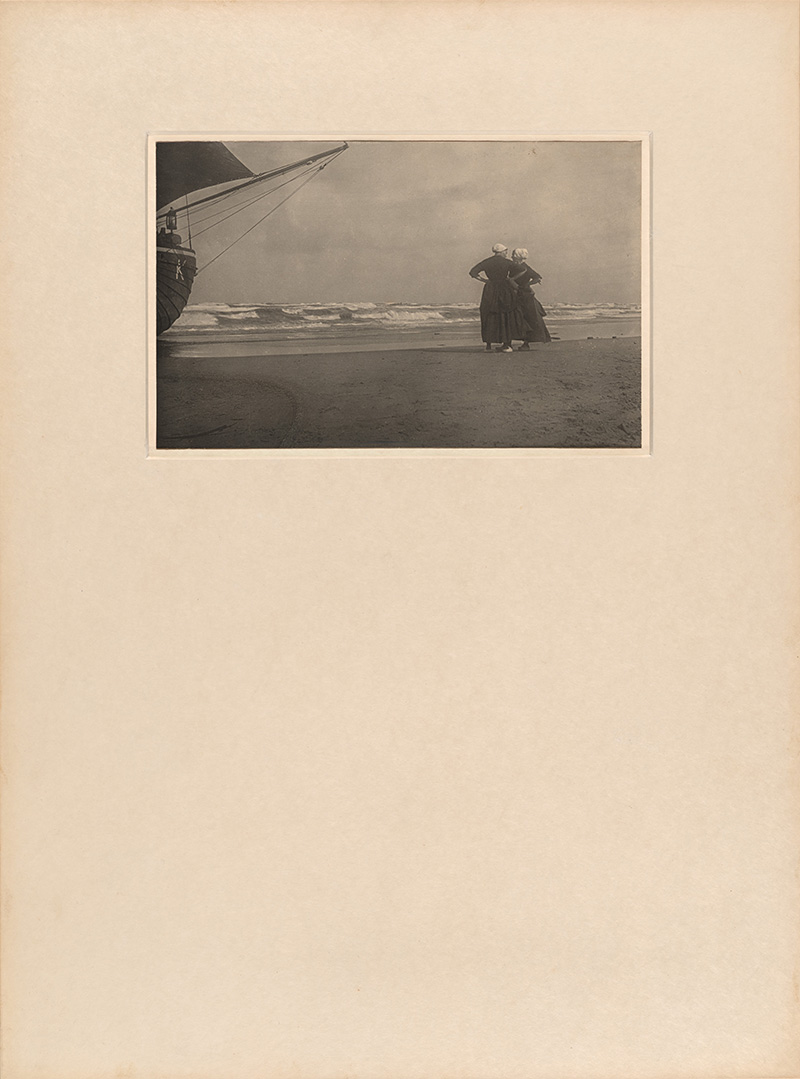

Alfred Stieglitz, Gossip—Katwyk, 1894, carbon print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.194

Key Set number 208

In the 1890s and early 1900s, when Stieglitz prepared his large carbon prints for display, he frequently mounted the print on a cream board and matted it with an eight-ply board covered with cream Japanese vellum. Sometimes the window mat covered the edge of the print, and sometimes he left a space of 1/4 inch around it. For vertical prints, he often left twice as much space on the bottom than on the top; for horizontal prints, he often left three-and-one-half times as much space at the bottom than at the top.

City of Ambitions_small.jpg)

Alfred Stieglitz, The City of Ambitions, 1910, printed in or before 1913, photogravure on beige thin slightly textured laid Japanese paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.308

Key Set number 342

Around 1910, when he was preparing the large (approximately 13 1/4 × 10 1/4-inch) photogravures that he made at this time, Stieglitz dry-mounted the print onto a cream board and covered it with a cream window mat (often 25 × 18 1/2 inches), leaving a space of 1/4–1/2 inch around the print. For vertical prints, he frequently left twice as much space at the bottom than at the top.

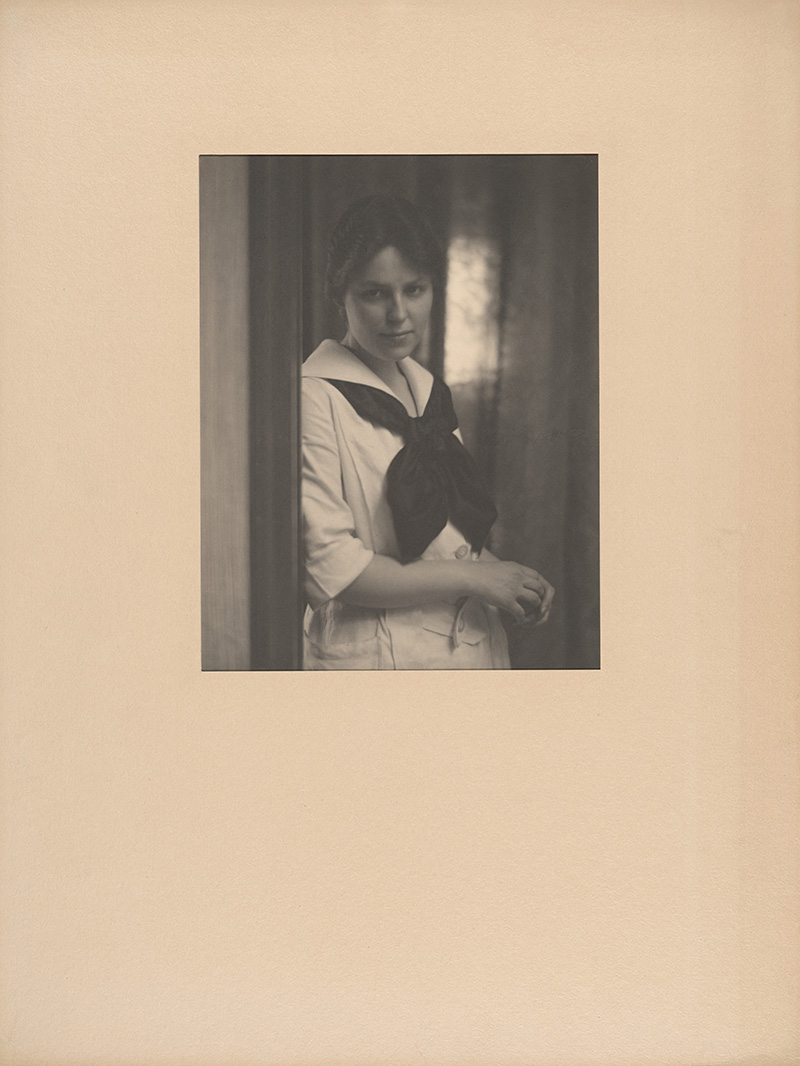

Alfred Stieglitz, Marie Rapp, 1914, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.349

Key Set number 392

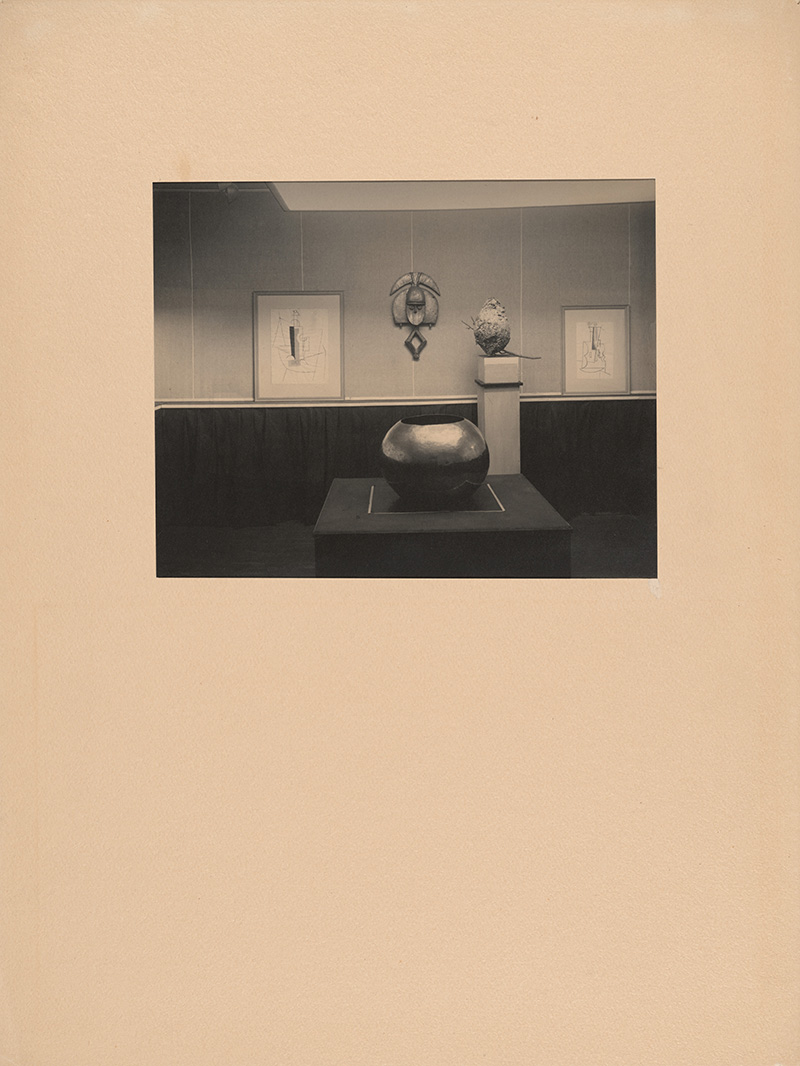

Alfred Stieglitz, 291—Picasso-Braque Exhibition, 1915, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.374

Key Set number 393

In the mid-1910s, Stieglitz frequently selected a light beige mount board that was more elongated and not as wide as his earlier boards, often 15 × 20 inches. He used a light beige, single-ply window mat with a toothy texture and allowed it to slightly overlap the edge of the print. For vertical prints, he often left two-and-one-half times as much space at the bottom than at the top; for horizontal prints, he often left three times as much space at the bottom than at the top.

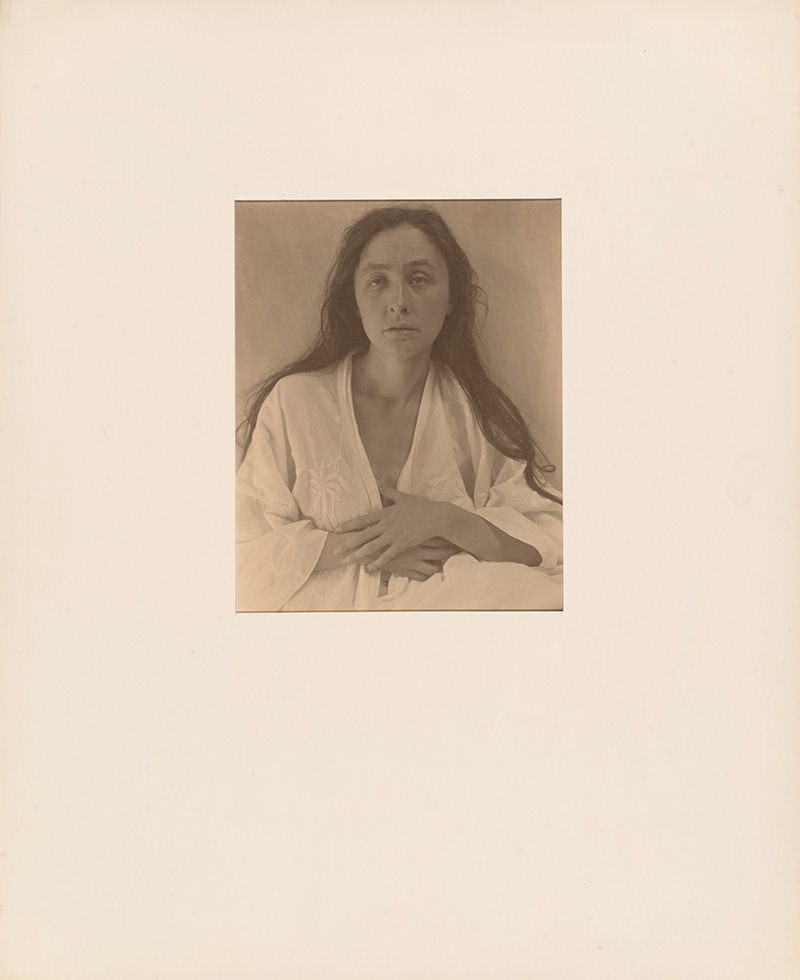

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1918, palladium print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1980.70.88

Key Set number 499

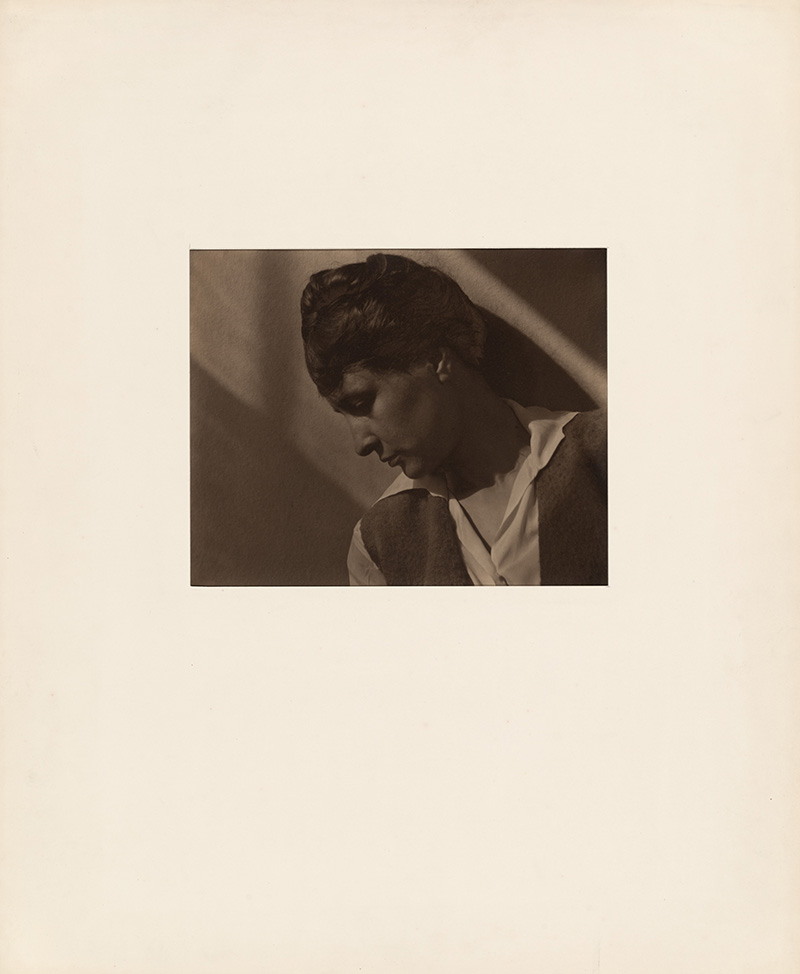

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1918/1919, palladium print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1980.70.90

Key Set number 561

When Stieglitz mounted his early portraits of Georgia O’Keeffe in the late 1910s and early 1920s, he frequently adhered the untrimmed print onto a beige board and covered it with a cream or antique white window mat (depending on the tones of the print) with a smooth surface. For his 8 × 10-inch prints, he often used mounts that were 22 × 18 inches. For vertical prints, he usually left almost twice as much space on the bottom of the print as on the top; for horizontal prints, he usually left two-and-one-half times as much space at the bottom than at the top.

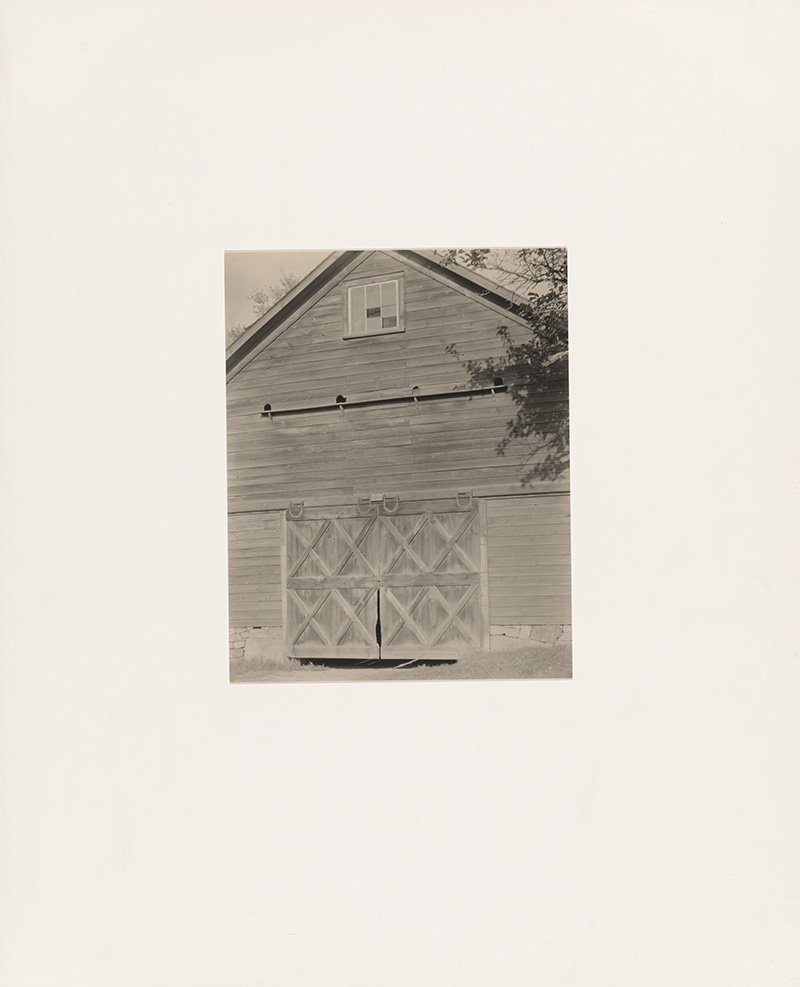

Alfred Stieglitz, The Barn, 1922, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.532

Key Set number 784

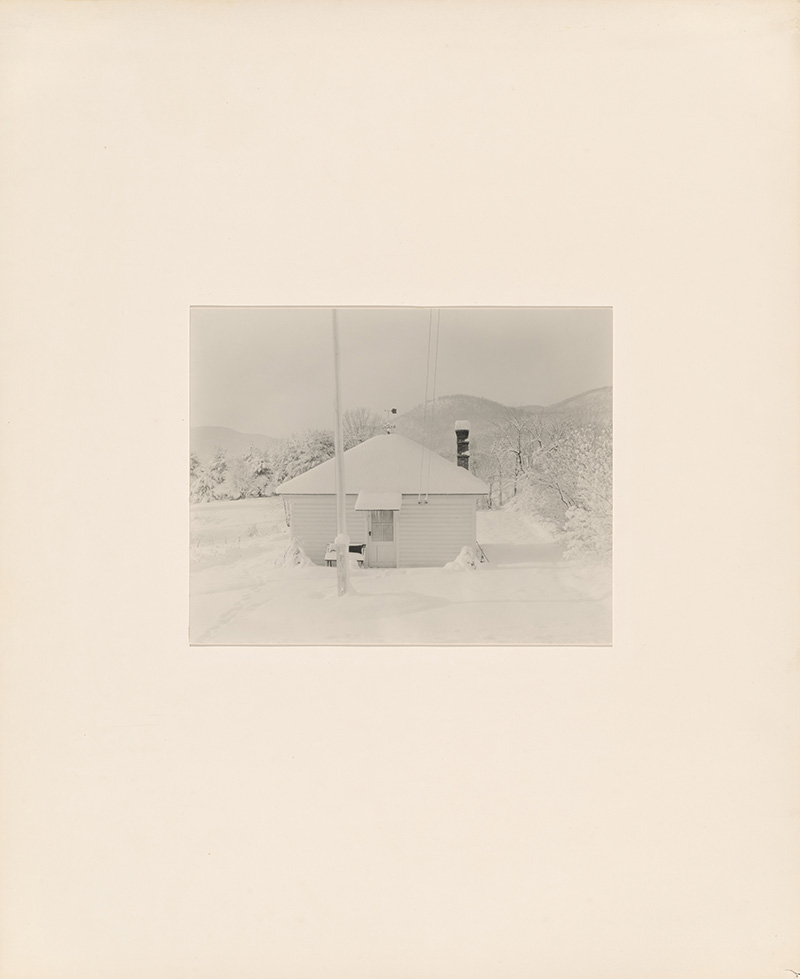

Alfred Stieglitz, First Snow and the Little House, 1923, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.624

Key Set number 863

Stieglitz’s method of mounting his prints changed considerably in the 1920s, as he frequently abandoned window mats altogether. He usually dry-mounted a photograph first to the back of a rejected print (to prevent it from curling), then to a thin, white paper board, trimmed the mounted print to the edge of the image, and adhered it onto a cream or sometimes antique white mount (depending on the tones of the print). He mounted his 8 × 10-inch prints onto boards that were approximately 22 × 18 inches. For vertical prints, he usually left 1 inch more at the bottom than at the top; for horizontal prints, he usually left only 1/2 inch more at the bottom than at the top.

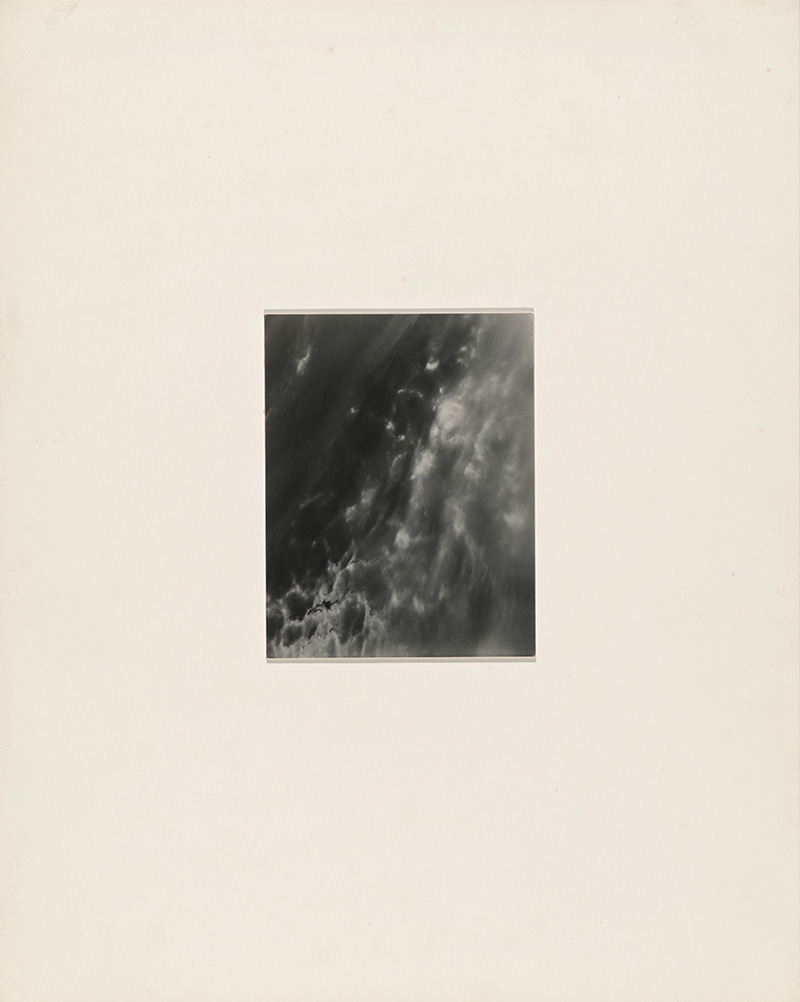

Alfred Stieglitz, Songs of the Sky or Equivalent, 1923/1929, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.961

Key Set number 985

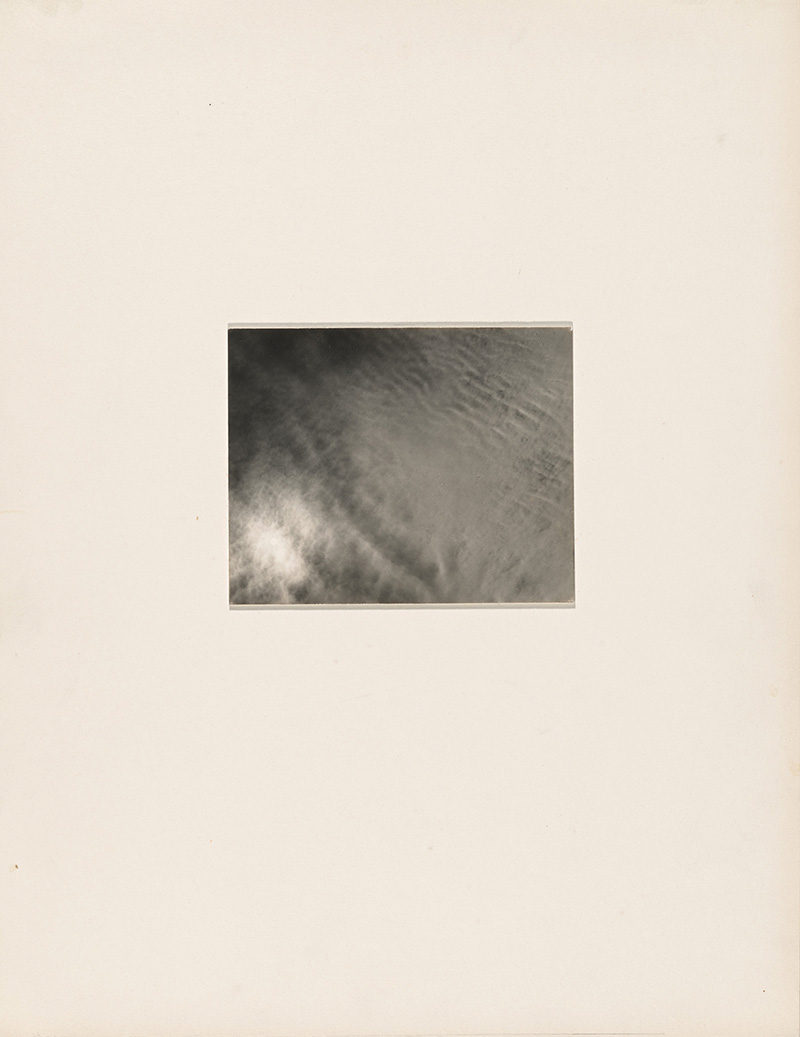

Alfred Stieglitz, Equivalent, possibly 1926, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.963

Key Set number 1169

With his photographs of clouds made from 1923 to 1934, Stieglitz usually dry-mounted the print to the back of a rejected print (to keep it from curling), which he then dry-mounted to a thin, white paper board. He trimmed the mounted print to the edge of the image and adhered it onto a light cream board. For those photographs made with his 4 × 5-inch camera, he usually used a board that was 13–14 inches high and around 10 3/4 inches wide. For vertical prints, he usually placed them slightly above the center; for horizontal prints, he usually left about 1 inch more at the bottom than at the top.

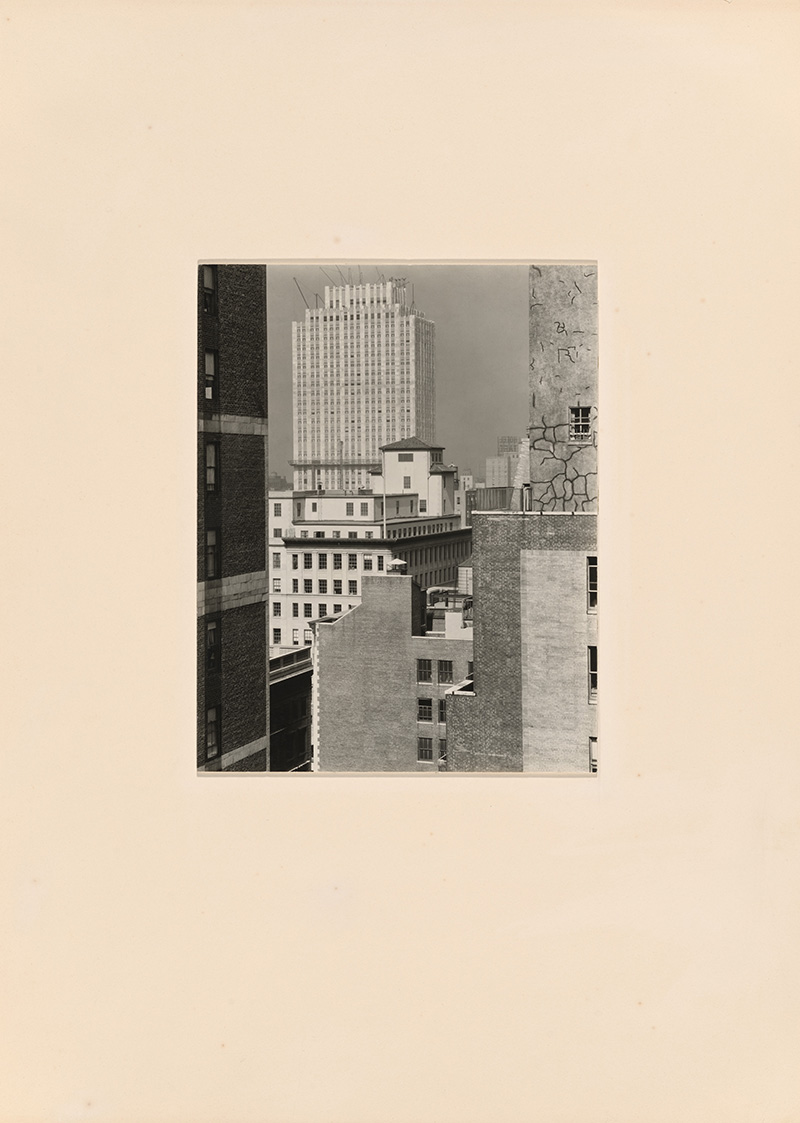

Alfred Stieglitz, From My Window at An American Place, Southwest, April/June 1932, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.1240

Key Set number 1459

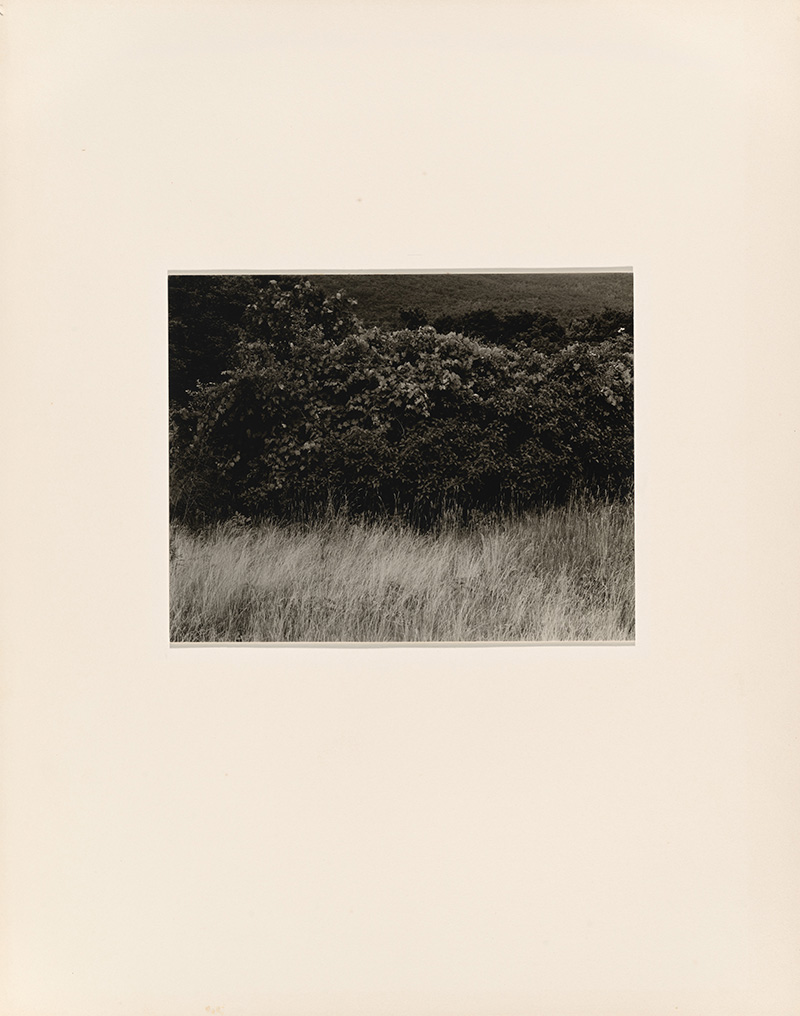

Alfred Stieglitz, Hedge and Grasses—Lake George, 1933, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.740

Key Set number 1508

In the 1930s, Stieglitz continued to eschew window mats. Instead, he dry-mounted a photograph to the back of a rejected print (to prevent it from curling), then often dry-mounted it to a thin, white paper board. He trimmed the mounted print to the edge of the image and adhered it onto a cream or sometimes antique white board (depending on the tones of the print). He mounted his 8 × 10-inch prints on boards that were approximately 22 × 18 inches. For vertical prints, he usually left 1–2 inches more at the bottom than at the top; for horizontal prints, he usually left only 1 inch more at the bottom than at the top.