Carrie Mae Weems, one of the most important contemporary artists working in the United States, has long been fascinated with Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s The Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial. Installed on the Boston Common in 1897 and reworked in a 1900

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled, 1996, printed 2020, 7 inkjet prints with sandblasted text on glass in wood frames, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 2020.96.1.a-g

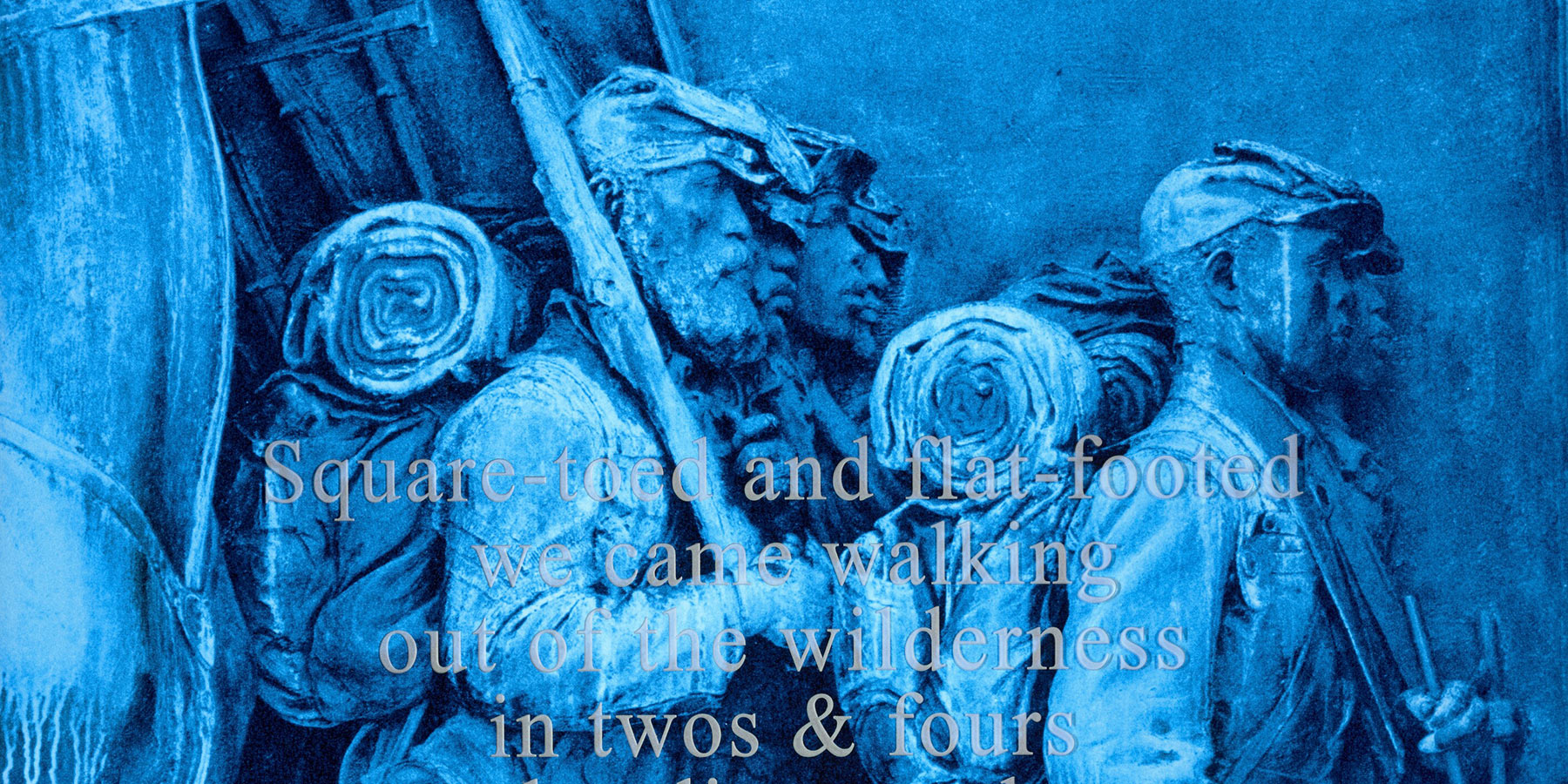

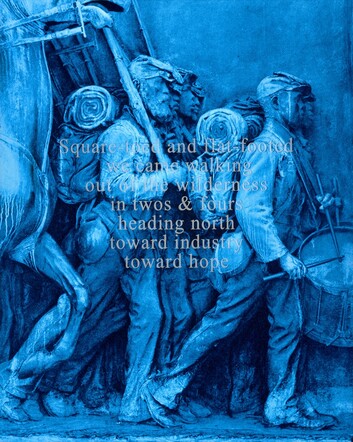

Weems first used an image of The Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial in her highly acclaimed series From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, 1995–1996, consisting of approximately 30 reproductions of 19th- and 20th-century photographs. Some of the pictures address photography’s problematic role in perpetuating racist ideas, while others call attention to the unknown African American subjects of now-celebrated pictures, whose images were almost always used without their permission. One of the pictures in the series is a photograph by Richard Benson of some of the soldiers depicted in The Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial. Weems cropped and reprinted Benson’s picture in red and covered it with a sheet of glass etched with the words “Restless through the longest winter you marched and marched and marched.” By focusing on the soldiers, Weems diminishes the heroism of Colonel Shaw, who towers above them in the sculpture, and instead celebrates the African Americans.

When she received a commission to commemorate the opening of a library on the South Side of Chicago, Weems returned to The Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial in

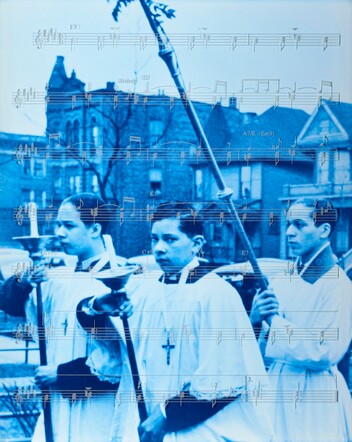

The second and sixth pictures in the series are reproductions of photographs by Russell Lee made outside a church on the South Side of Chicago for a book he was working on with the celebrated author Richard Wright, 12 Million Black Voices, 1941. A page of the score of Duke Ellington’s “Come Sunday” is etched into the glass over the photograph on the left, and a page of the score of Miles Davis’s “All Blues” is etched into the glass over the photograph on the right.

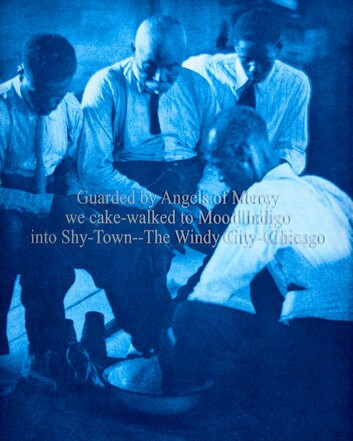

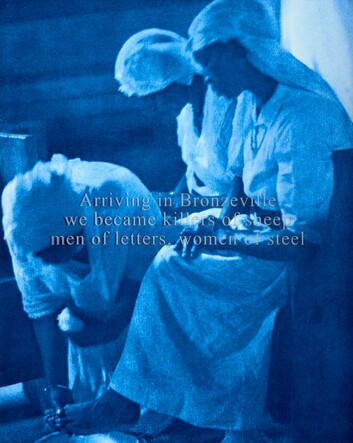

The third and fifth pictures are reproductions of photographs by Doris Ulmann from her book Roll, Jordan, Roll with a text by Julia Peterkin. They depict the ceremonial act of foot washing, an act that signals service and humility. The text etched into the glass alludes to the importance of Chicago for African Americans and to the new professions it offered them.

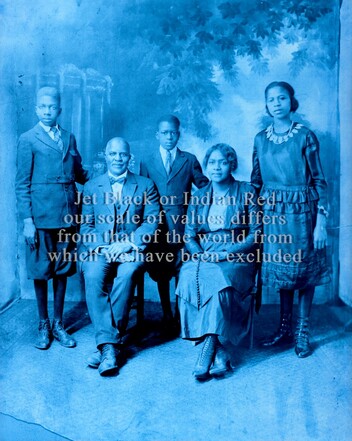

The middle photograph, the heart of the sequence, is of the Morris Williams family. Like so many African American families of the time, they were part of the Great Migration and moved from Texas to Chicago in the 1920s in search of jobs and freedom from prejudice. We do not know who the photographer was, but because of segregation, it was likely an African American studio photographer.

As we read the text etched into the glass on top of these pictures, we quickly see that Weems is poetically alluding to the history of African Americans since the Civil War: “Guarded by Angels of Mercy we cake-walked to Mood Indigo into Shy-Town--The Windy City--Chicago”; “Arriving in Bronzeville we became killers of sheep men of letters, women of steel”; “Jet Black or Indian Red our scale of values differs from that of the world from which we have been excluded.” In addition, the references to Ellington’s “Mood Indigo,” Davis’s “All Blues,” and pictures of foot washing and a processional covered with glass etched with a page of the score of Ellington’s “Come Sunday” infuse the piece with religious overtones and allusions to the power of music. Together these seven pictures create a work that is, as the “Come Sunday” lyrics note, a plea to God to “please look down and see my people through.” In this exceptionally compelling piece Weems reframes the work of white artists—Saint-Gaudens, Benson, Lee, and Ulmann—to present a new and more complex narrative centered on African American history, culture, and experience.

Banner detail: Carrie Mae Weems,