Rare Early Photographs of African American Life

A new addition to our collection of 248 early photographs by and of African Americans give us a glimpse of Black life, entrepreneurship, and self-expression during the era.

These pictures tell stories of their creators and subjects, revealing a fuller picture of the American experience.

In some pictures from before the Civil War, African Americans are photographed with the children of the white families that enslaved or employed them. Other photographs of those who had endured or escaped slavery became important tools in the fight for abolition.

Yet African American photographers operated highly successful photography businesses. While their studios catered to everyone, Black or white, photography provided a new means of self-representation. Especially after the Civil War, it allowed African Americans to celebrate successes, document families, and express identity.

A Collector’s Eye

It all started with a photograph that cost 50 cents. Ross Kelbaugh’s lifelong fascination with photography began with an image of a Civil War cavalryman he purchased when he was just 12.

It wasn’t until later in the 1970s that Kelbaugh began to seriously collect photographs. He scoured shops, antique shows, auctions, and flea markets looking for intimate mementos from the early days of photography. In the process he came across pictures of African Americans. Most collectors weren’t interested in them. But Kelbaugh, by then a history and social studies teacher in Baltimore County, Maryland, saw these photographs as a teaching tool to connect his students with the nation’s past.

Kelbaugh has spent some 50 years searching for, collecting, and studying hundreds of rare photographs. We recently added 248 photographs from his collection to ours. Continue scrolling to explore a selection of these remarkable examples of the nation’s earliest photographs.

Early African American photographers

Photography made waves when it arrived in the United States in 1839. Daguerreotypes, images made on silver-coated copper plates named after their French inventor Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, quickly became a craze. Daguerreotypes were much more affordable than traditional painted or drawn portraits, so studios spread rapidly across the country.

The Ross J. Kelbaugh Collection includes 11 photographs by celebrated early Black photographers James Presley Ball, Glenalvin Goodridge, and Augustus Washington. All three opened studios, capitalizing on the new demand.

“Ball’s Great Daguerrean Gallery of the West” was a successful operation in Cincinnati, Ohio. Goodridge ran a studio in York, Pennsylvania, while Washington worked in Hartford, Connecticut, until he moved to Liberia in 1852.

White clients visited their studios for touching family portraits like Ball’s The Hercules Family or distinguished individual portraits like the one here by Washington. Goodridge showed his skill as a photographer by capturing the cat in his studio chair despite photography’s long exposure times.

Records of slavery—and those who fought for its abolition

Photography was an important tool for documenting the atrocities of slavery and advocating for its abolition.

Civil War photographers like James F. Gibson took pictures of formerly enslaved people who had crossed into Union territory (called “contraband” during the war). Their widely circulated images became testaments for the Union cause and often sold to support abolitionist efforts. Henry P. Moore’s photograph shows workers at a plantation on Edisto Island in South Carolina. By the time Moore took it, the slave owners had mostly fled as Union forces pushed into the area. The island became a refuge for those who had been freed or escaped slavery.

Abolitionist speaker and writer Frederick Douglass believed that images of African Americans like himself could help dissolve stereotypes and challenge racism. Leaning into the new technology, Douglass became one of the most photographed Americans in the 19th century. Photographs like this carte de visite (a print the size of a calling card) were sold at his speaking engagements and included by Douglass in with his letters. Beyond helping the fight for racial equality, Douglass also believed photography would have a significant impact on society, as “men of all conditions may see themselves as others see them.”

African American accomplishment

In several photographs, African American subjects hold objects symbolic of their newfound freedoms and accomplishments in the wake of emancipation. In a small tintype (an image on a thin sheet of iron), a young boy stands with a school bag over his shoulder. Another shows a woman prominently holding a book. Both refer to the opportunity for education, which African Americans had previously been denied.

An ambrotype (an image on a translucent glass plate) of a young Civil War soldier records one of the early Black enlistees who fought to preserve the Union and put an end to slavery. The sitter paid a premium for gold embellishments on the buttons of the soldier’s jacket and the knife in his belt.

Stylish subjects

When sitting for their portraits, these subjects dressed their best. Photography studios allowed African Americans who had gained freedom and wealth to record their success. Accessories like top hats or sheer lace gloves showed their prosperity. And for a price, photographers would hand-color photos. Boston’s Tyler & Co studio colored the dress worn by a young woman pink and adorned her with a necklace.

The identities of both subjects and photographers have often been lost over time. Some photographs hold clues, though. When Kelbaugh purchased the tintype of the seated woman, he discovered that it included a slip of paper with the name “Annie” written on one side and the words “remember me” on the reverse.

You may also like

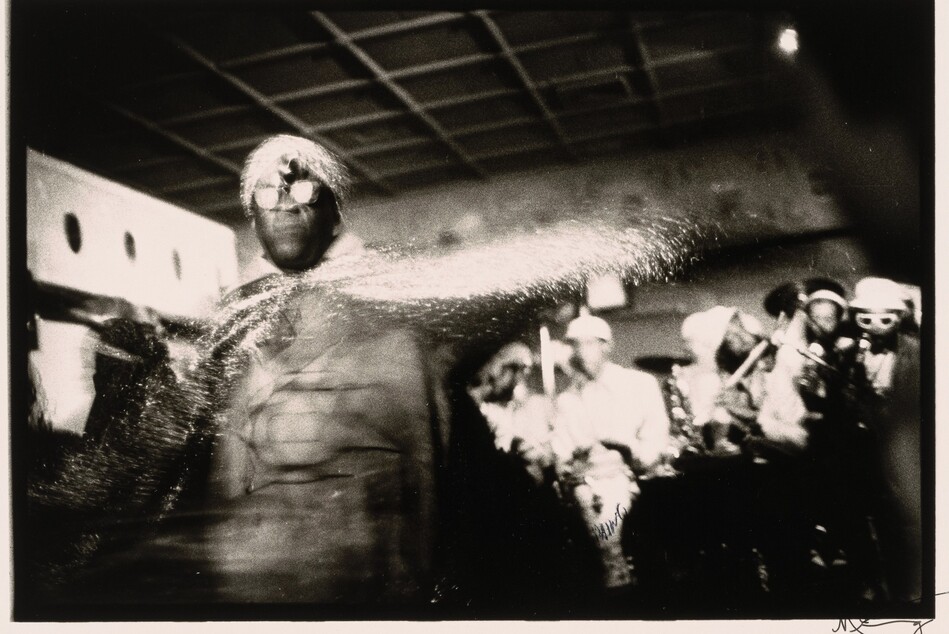

Article: What Is the Black Arts Movement? Seven Things to Know

Learn how the "cultural revolution in art and ideas" celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty.

Article: Who Is Elizabeth Catlett? 12 Things to Know

Meet a groundbreaking artist who made sculptures and prints for her people.