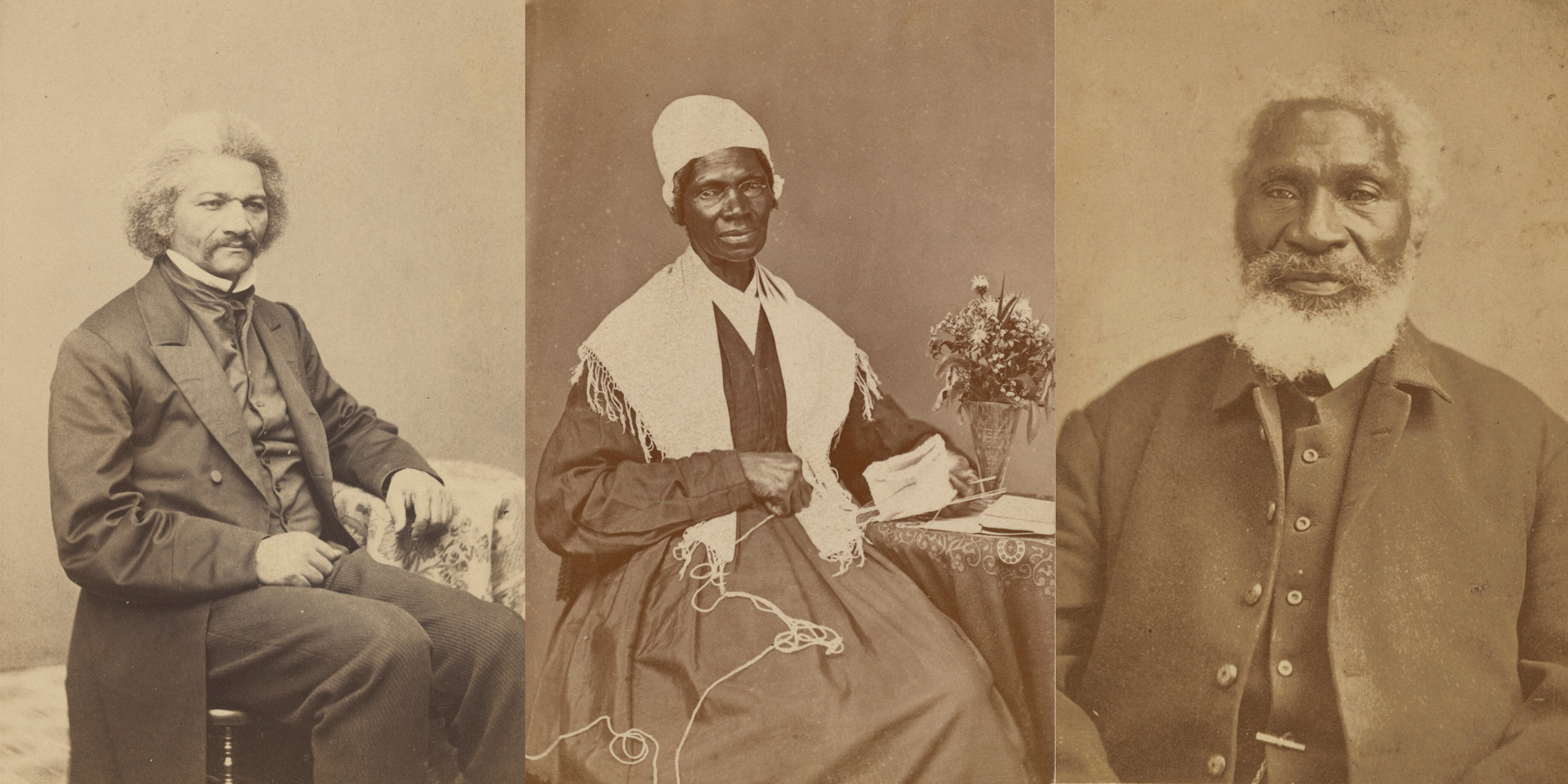

1. Frederick Douglass

This 1864 print is one of hundreds—Douglass was among the most photographed people of the 19th century. The speaker and abolitionist saw the power of photography. “It is evident that the great cheapness and universality of pictures must exert a powerful, though silent, influence upon the ideas and sentiment of present and future generations,” he said.

Photographs like this carte-de-visite (a print the size of a calling card) were sold at his speaking engagements. Douglass also included them with his letters.