Introducing the Food for Thought Series

In this series, chefs, farmers, historians, scholars, and other thinkers share their takes on food, consumption, cooking, and eating.

Art & Society

min read

Food is a basic human need. In our Food for Thought series, James Beard Award–winning journalist, scholar, and writer Cynthia Greenlee hosts a gathering of historians, food journalists, poets, chefs, and farmers and invites them to riff on food-related works of art in our permanent collection.

While living in the Windy City for almost a decade, I often took a long walk with my very large hound through the lofts and industrial buildings of the near West Side of Chicago. We were just nine blocks from the School of the Art Institute where Black artist and printmaker Eldzier Cortor had studied in the mid-1930s.

We were just nine blocks from the School of the Art Institute where Black artist and printmaker Eldzier Cortor had studied in the mid-1930s.

I was there during the great real estate boon that caused the 2008 sub-prime lending crisis, and vacant lots were being turned into luxury apartments for a new mobile class. One day my dog pulled toward and then away from a murky pool of muddy water bubbling ever so slightly. I wondered what could be down there.

Curious about it, I mentioned the fizzing pool to a long-time neighborhood resident artist. He explained that our industrial lofts stood on the bones and sinew of the former stockyards and slaughterhouses from Chicago’s pre-fire (1871) history. He told me that the bubbles are the slow off-gassing of centuries of offal (entrails and internal organs of animal slaughter) and bone—and, yes, misery.

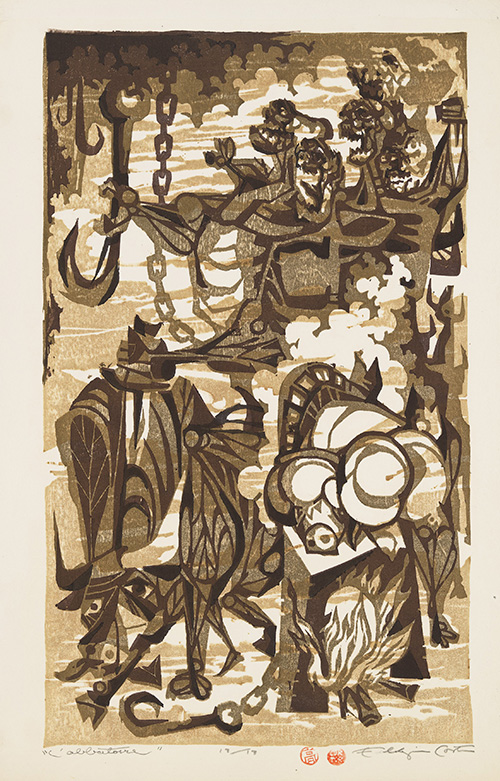

Eldzier Cortor, L'Abbatoire No. 1 (Slaughterhouse No. 1), 1949, color woodcut on wove paper, Reba and Dave Williams Collection, Florian Carr Fund and Gift of the Print Research Foundation, 2008.115.42

The Violence Behind a Choice Cut of Meat

Cortor’s surrealist rendering of a slaughterhouse invites us to think about what bodies and what histories are involved in the abattoir and its fire stack. In Cortor’s work, smoke reminds us of the still-raging fire. It wraps around what could be chicken legs, and the elongated bodies of human figures, and the head of a cow, and a slab of meat on a hook moving purposefully from the killing floor to the end point of the assembly line: a choice cut of meat for our palates and our plates.

As we see in his color woodblock, the abattoir (French for slaughterhouse) endures, bubbling up its toxic stew to the surface of our everyday. It runs around the clock; its smokestack is never cold, its dishes always at the ready. But who and what are served forth in this stench we stumble upon in Cortor’s work?

Cortor wants us to think about the relationship of humans and animals like the two sides of the same coin.

There is no neatly packaged meat in our grocery stores without the abattoir, though we try to hide its awful effects from polite society. What do you see here? Chaotically arranged human and animal parts? Cortor wants us to think about the relationship of humans and animals like the two sides of the same coin. The canvas’s primary color, blood red, and the hooks and chains that surface out of the color woodblock remind us of the violence that made the industrial “new” world.

Eldzier Cortor Tells the Stories of Black Bodies

Cortor is most famous for his Southern Landscape, painted in 1941. If we search sites where gallery and museum folks talk about him, they note that he was one of the few, and perhaps the first, to focus his art on African-descended women, many of them nudes. Cortor’s work reminds us of both pain and pleasure—which is the “both/and” of how we come to eat. Something has to be taken apart for us to have a cuisine, someone has to work to make it so. This work asks us to consider where our food comes from and who makes it possible.

This work asks us to consider where our food comes from and who makes it possible.

For Cortor, the focus on the slaughterhouse most likely came from his memories of an actual slaughterhouse in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, as well as his childhood in Bronzeville, a neighborhood known in Chicago today as “the Gap.” It is the gateway to the city’s predominantly African-descended South Side, and it is where the many slaughterhouses and butcheries found a home.

Eldzier Cortor, L'Abbatoire, 1950s, woodcut, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of the artist in memory of Sophia Rose Cortor, © Eldzier Cortor, 2014.352, Digital image © Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala / Art Resource, NY

Cortor is the griot (West African historian and storyteller) of our collective middle passage, as African-descended people live, figuratively and literally in the in-between of cities, nations, landscapes, cultures. This color block is just one of a series of his images, some invoking a slave ship, all in the surrealist vein. The beauty and horror of Black life unfold in the sticky matter of Cortor’s works. There is barely a discernable difference between human and animal in the series and in this particular image. We are both flesh, to be consumed. We [as Black people] are consumed, ground up by our national abattoir, as we labor in the dirty, bloody work of actual butchery and making the nation thrive.

The beauty and horror of Black life unfold in the sticky matter of Cortor’s works.

What we have to say about food, about eating, about how both come to us is a dialogue with a long history. Whatever our food is, however we are fed, we encounter Black bodies and their history. This piece reminds us of that encounter, calls us to it. Bubbling up everywhere . . . all of the time.

Sign up to our newsletter for the next edition in our food series.

Thank you. Please check your email for a confirmation message.

Sharon P. Holland is the Townsend Ludington Distinguished Professor of American Studies in the department of American Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is the author of the forthcoming book (fall 2023), an other: a black feminist consideration of animal life from Duke University Press.

March 10, 2023