Introducing the Food for Thought Series

In this series, chefs, farmers, historians, scholars, and other thinkers share their takes on food, consumption, cooking, and eating.

Art & Society

min read

Food is a basic human need. In our Food for Thought series, James Beard Award–winning journalist, scholar, and writer Cynthia Greenlee hosts a gathering of historians, food journalists, poets, chefs, and farmers and invites them to riff on food-related works of art in our permanent collection.

When was the last time you dressed for dinner? Not to go out to a fancy restaurant or a holiday feast, but just an ordinary dinner, eaten at home, in the middle of the week?

The custom of dressing up to eat may now seem foreign to us, but it was part of the daily routine for elite Americans in the 19th-century Gilded Age, a period of tremendous industrial growth and economic corruption that deepened divides between when the wealthy and the poor, leading to social unrest. Clothes were made not only according to a specific person’s taste and class but also to fit special times and occasions. Each outfit had its own specific functions and appropriate look.

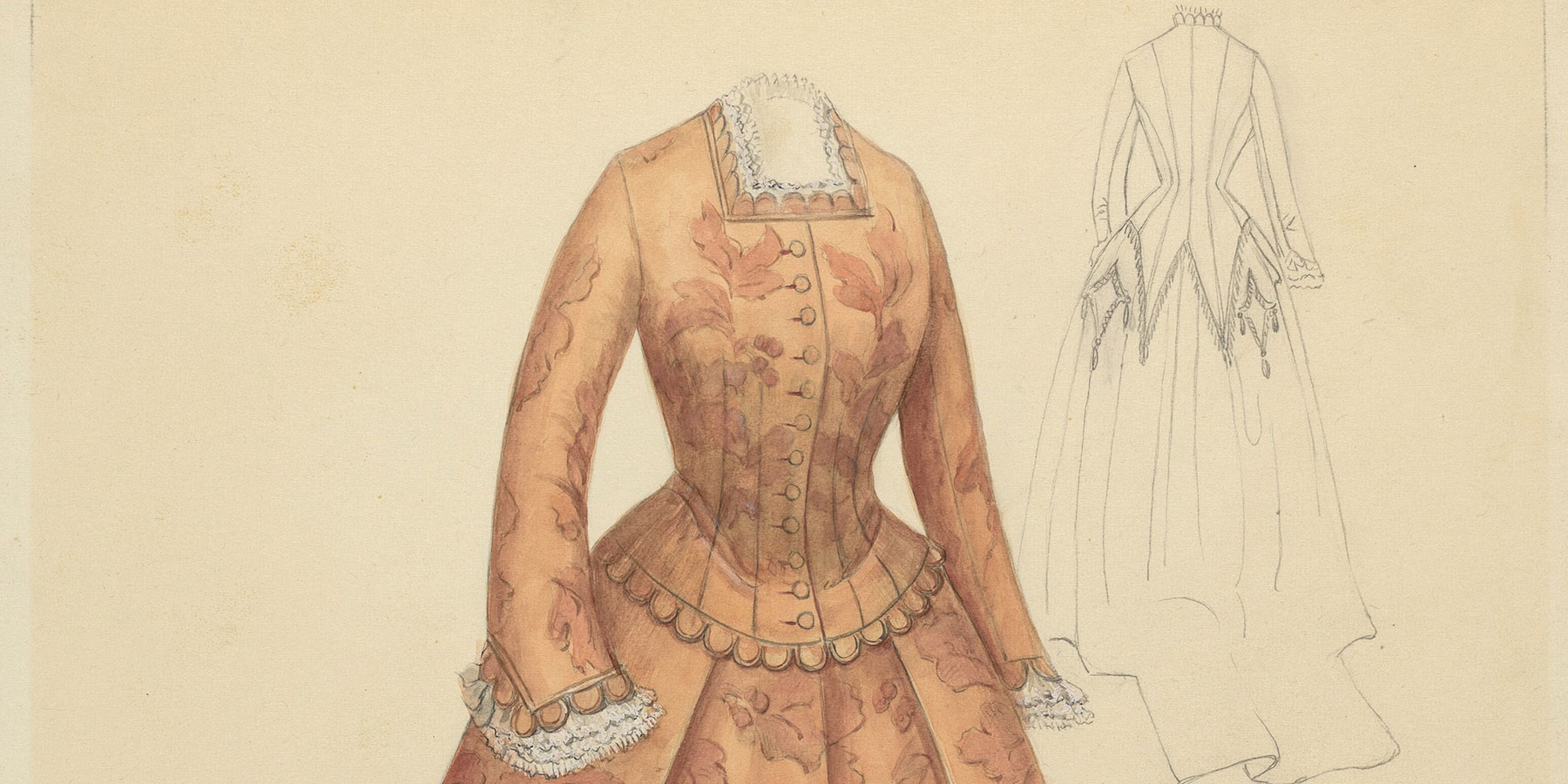

Hedwig Emanuel, Dinner Dress, 1935/1942, watercolor and graphite on paperboard, Index of American Design, 1943.8.17416

Indeed, it was not uncommon that a wealthy woman would change her clothes four or five times a day. And dinner—whether it was a social gathering or a family event—required its own special dress. Etiquette books and manuals detailed the specific fabrics, colors, sleeve length, and cleavage that was appropriate for the dinner table, and they separated dinner from other evening engagements, such as balls and parties.

Dressing for Dinner

While food was certainly at the center of dinners, they were mainly a social function, even if it was only between parents and children. As such, dressing for dinner was not just a practical requirement. The purpose was to establish or maintain one’s reputation.

Dinner attire was supposed to be formal yet still modest—especially for the hostess, whose dress was never to eclipse that of her guests. Short sleeves and low necklines might have been helpful to avoid staining clothes with soup or gravy, but they were often reserved for evening balls that included dancing.

Dinner dress, Charles Frederick Worth, c. 1877, silk, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Estate of Mrs. Pierpont Morgan, 1925, 25.63a, b

Custom demanded covering neck and arms. Yet the emphasis on elegant simplicity did not prevent the use of rich fabrics (usually silk) to show the wearer’s financial status.

Dress requirements did not only apply to people, however. The table itself had to be “dressed for dinner,” with clear instructions on the color and fabric of placemats and the design of napkins.

Table arrangement pieces changed according to the season and occasion, ranging from flowers and fruit decorations to elaborate vases and small sculptures. There were clear rules for how to place one’s napkin and the order of serving food. Seating arrangements were meant to portray an image of elegance and wealth.

Dining in the Gilded Age

The dress (which also appears in the image below), dated to 1877, belonged to Frances Louisa Tracy Morgan, the wife of the J. P. Morgan, a famous banker of the late 19th-century Gilded Age. Despite its luxurious satin, which would have gleamed in gas light, the long sleeves and overall simplicity of the silhouette suggest it was worn for a typical dinner. The dress’s rich brown-and-orange color palette, as well as its intricate pattern of oak leaves, made it a perfect choice for a fall or winter dinner, such as Thanksgiving.

Dinner dress, Charles Frederick Worth, c. 1877, silk, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Estate of Mrs. Pierpont Morgan, 1925, 25.63a, b

While Mrs. Morgan probably did not play an active part in preparing the food or setting the table, her choice of dress was her contribution to the dinner making. It was the act of dressing up—and thus acknowledging the occasion—that made the dinner Mrs. Morgan’s event.

Gilded Age dinners were elaborate, often with five or six courses. Soups, oysters, and game meat were common in fall dinners, often accompanied with sweet pudding for dessert. And while we can only guess what food was served during Mrs. Morgan’s dinner, it is her dress that serves as a memento.

The Dress in the Index of American Design

In 1925, the dress was donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It certainly symbolized the passing of an old world in favor of the new, as new dinner etiquette and dress became fashionable.

And perhaps it was the dress’s status as a museum artifact that made it such a good candidate, in 1935, to be drawn for the Index of American Design. This project of the Works Progress Administration aimed to create a visual record of arts and crafts in the United States. The dress was supposed to capture the American spirit, and the leafy motif indeed gives the sense of a New England late summer or autumn.

Dinner dress, Charles Frederick Worth, c. 1877, silk, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Estate of Mrs. Pierpont Morgan, 1925, 25.63a, b

However, the dress was created by the famous French designer Charles Worth—not by an American. The illustrator for the Index certainly tried to make it more “American,” showing the dress as simpler than it actually is. We don’t see, for example, the underskirt’s fringe or how the back bodice consists of six interlocking pieces. In a post-Depression United States, some designers strove for a new simplicity, distinct from both early 1920s glamour and the ornate European styles that served as the era’s high fashion.

But maybe what made this dress worthy to be included in the Index was not the designer, nor its style, but its wearer, and the purpose for which it was worn. The specific etiquette rules of how to wear this dress for dinner are what made it American and the legacy of a long-gone tradition to be documented. The Index might not be able to preserve the act of making dinner, but through the dinner dress, we get a glimpse of what it meant.

Sign up to our newsletter for the next edition in our food series.

Thank you. Please check your email for a confirmation message.

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox is a historian who writes about the intersections between fashion, politics, and modernity, particularly the role of visual and material culture in social movements. Her new book is Dressed for Freedom: The Fashionable Politics of American Feminism (University of Illinois Press, 2021). She has published both in academic journals and books and in popular media, such as The Washington Post, The Conversation, Public Seminar, and History News Network.

December 02, 2022