Walter Simon Melion

Praying through Prints: Technologies of Affective Piety and Image-Based Devotion in Dutch and Flemish Prayer Books, 1480–1650

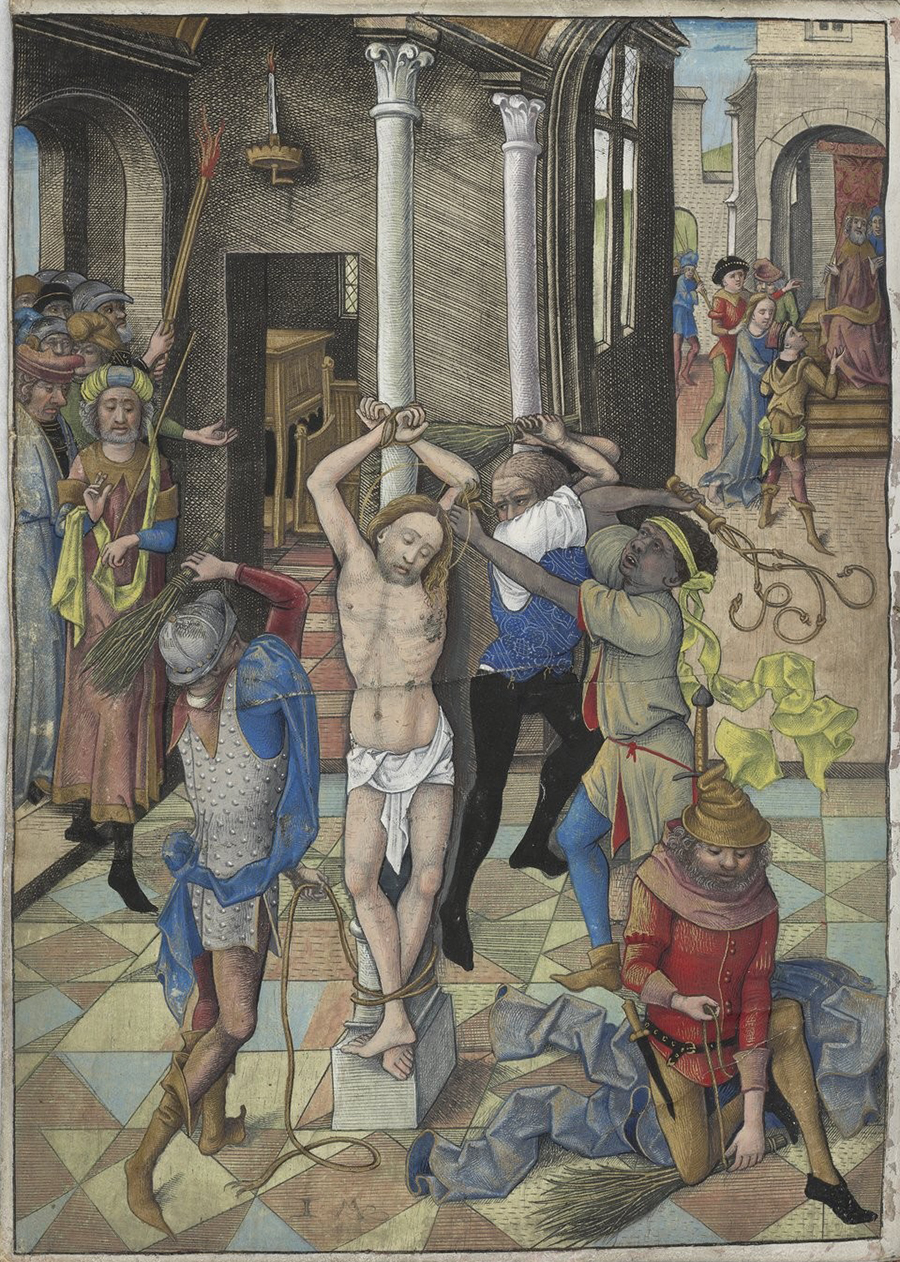

Israhel van Meckenem, Flagellation of Christ in the Presence of Pilate, with Christ Brought before Herod, from the Great Passion, c. 1480, engraving, highlighted in gold, with touches of pen and red ink (on Christ’s feet), c. 205 × 151 mm, from Groendaal Passion, fol. 24r, late 15th century, each folio c. 260 × 204 mm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2003.476

I devoted most of my time at the Center to completing three chapters of my book in progress, “Praying through Prints: Technologies of Affective Piety and Image-Based Devotion in Dutch and Flemish Prayerbooks, 1480–1650.” Three of those newly written chapters focus on a triad of late 15th-century manuscripts—in London, New York, and Paris, respectively—organized around Israhel van Meckenem’s Great Passion series. Assessing the format and function of these embedded prints required a reassessment of what makes Van Meckenem’s Passion so distinctive—namely, its scriptural fidelity and aggregative spatiotemporal structure consisting of clustered scenes excerpted from the synoptic Gospels and the Gospel of John. The Great Passion, in other words, aspires to be the pictorial version of a Gospel harmony. Based as they are on a close reading of Scripture, attentive to multiple details drawn from the Gospels, and assembled into temporally coherent sequences of episodic scenes on the exegetical model of a harmonization, the prints function in the Groendael Passion (the first of three manuscripts I examine) as the common ground for the modally distinct amplifications layered upon them by the prayer book’s complex apparatus of interwoven Dutch and Latin texts. One might in fact claim that Van Meckenem’s Passion series provided the visual anchor that safeguarded the Groenendael Passion’s coherence, its multimodal unity in multiplicity. The juxtaposed Latin and the Dutch texts, through their mutual attachment to the printed images, can be seen to work in tandem, as complements, the Dutch arousing horror and shame conducive to self-accusation and penitential contrition, the Latin harnessing that self-loathing to the task of meditative reflection and contemplative devotion.

Illuminated by Robinet Testard and Jean Bourdichon for the use of Charles of Orléans, Count of Angoulême, the Heures de Charles d’Angoulême likewise incorporates a complete set of Van Meckenem’s Great Passion, overpainted by Testard and embedded in a French “Passion,” known as the Passion Isabeau. It was mainly adapted from the Pseudo-Bonaventure’s Meditationes vitae Christi, with an admixture of elements from Ludolph of Saxony’s Vita Christi, most importantly that text’s emphasis on fashioning a meditative image of Christ. Produced for Isabeau of Bavaria, wife of Charles VI, the Passion Isabeau starts with the raising of Lazarus and ends with Jesus’s entombment; for his Heures, to match Van Meckenem’s Passion, Charles commissioned chapters on the Resurrection and the journey to Emmaus. The scribe who copied this Passion text sometime from 1480 to 1496 adjusted it to ensure that it closely responded to the adjacent images. In fact, text and image work in tandem: the Passion not only offers close readings of the painted prints but is also read by them, in the sense that they function like prefaces, ensuring that the persons, places, and events described in the text are visualized in the manner pictured. The French Passion operates together with the illuminated versions of Van Meckenem’s Passion to call attention to a particular and recurrent theme: the way in which the redemptive mysteries were conferred by Christ on his followers through the testimony of their eyes, by way of sights now best communicated to us through the medium of images.

Israhel van Meckenem, Flagellation of Christ in the Presence of Pilate, with Christ Brought before Herod, from the Great Passion, c. 1480, engraving, c. 205 × 151 mm, from Heures de Charles d’Angoulême, fol. 80v, c. 1480–1496, with Robinet Testard (illuminator), transparent washes and body colors applied to engraving on paper, pasted onto parchment, each folio c. 210 × 155 mm, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, ms. lat. 1173

Assembled in the later 15th century, the manuscript prayer book in London (British Museum 1897,0103), which takes the form of a book of hours, utilizes Van Meckenem’s prints to entwine the Hours of the Virgin and the Hours of the Passion, so that the mysteries of the Incarnation and the Passion are meditated in tandem, the former coming to serve as a type or, better, a typological prophecy of the latter. Whereas books of hours traditionally placed the Horae beatae Mariae Virginis and the Horae Passionis side by side, this prayer book merges their constituent parts more insistently, assimilating them into a densely woven intertext. Whereas the Great Passion grafts the Passion onto the Marian hours, the Marian prayers implicitly insert Mary into those Passion scenes where she is absent and explicitly heighten her presence in those scenes where Van Meckenem has included her. This effect is heightened by the fact that most of the Latin prayers facing the prints across the prayer book’s opening are orationes (prayers) dedicated to the Virgin. In sum, the manuscripts in New York, Paris, and London reveal how determinative an apparatus of printed images could be to the form and function of a prayer book, and, conversely, how the meaning of these prints shifted from context to context as a direct result of their adjacency to texts whose readings they in turn inflect.

I was also able to draft a further chapter: “Material Poverty and Virtual Splendor in Brugge HS676 (c. 1610–1640), a Franciscan Devoten ghebedenboeck.” My argument is that this prayer book’s combination of simplicity and ostentation, its material and technical austerity (ink and paper, modest rubricated ornaments, and cut-and-pasted prints by engravers such as Philips Galle and Jan and Adriaen Collaert) surprisingly enhanced by lavish gilding, simultaneously plays upon the Franciscan conception of Mary’s exemplary humility and spiritual splendor. The contrast between the absorptive properties of the paper and ink and the reflective luster of the gold gilt heightens the contraposition of modesty and magnificence. As will be evident, this chapter of the book dwells on the signifying effects of a prayer book’s constituent materials and methods of production.

In between working on these four chapters, I was also able to write four articles: “The Cult of the Cor Jesu and Its Flemish Roots: Devotion to the Loving Heart of Jesus in Early Jesuit Emblem Books”; “Karel van Mander’s Pagan Gods and Vincenzo Cartari’s Imagini degli Dei degli antichi”; “Mercy, Sweetness, and the Lord’s Flesh: Hendrick Goltzius’s Ecce Homo of 1607”; and “Motus mixti et compositi: The Portrayal of Mixed and Compound Emotions in the Visual and Literary Arts of Europe, 1500–1700.” None of this would have been possible without the time and resources afforded me by the Center, its brilliant leadership, and superb administrative staff.

Emory University

Samuel H. Kress Senior Fellow, 2023–2024

After an extended summer research trip to the Netherlands, Germany, and Poland, Walter Simon Melion will return to his position as Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Art History at Emory University. In fall 2024, he will serve as convener and moderator of the three-day colloquium “The Affective and Hermeneutic Functions of the Mindful Picture.” He expects to write the final two chapters of “Praying through Prints” during academic year 2024–2025.