Tomáš Valeš

Human Bodies, Gender, Race, and the Academy of Fine Arts in Late 18th-Century Vienna

In my current book project, I focus on the changes in artistic education, practice, and patronage in late 18th-century Vienna. In the short window from 1766 to 1772, Vienna experienced an unprecedented development in art education, which helped to increase the international competitiveness of young artists and artisans in the city. In addition to the traditional Academy of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, other artistic schools or academies were established to serve different purposes.

Gertrude Cornélie Marie de Pélichy, Caritas Romana, after 1764, oil on canvas, Musea Brugge, Bruges, 0000.GRO1619.I

One of these was the Engraving Academy of Jacob Matthias Schmutzer, founded mainly with the support of Chancellor Wenzel Anton Kaunitz-Rietberg and Empress Maria Theresa. Schmutzer, as a gifted draftsman and engraver, studied for several years in Paris at the school of the German engraver Johann Georg Wille. Upon his return to Vienna, Schmutzer tried to use all of his newly acquired skills in his new Engraving Academy, which existed until 1772. Later, it was merged with other Viennese art academies into the United Academy of Fine Arts (vereinigten freyen Akademie der bildenden Künste). Schmutzer’s Engraving and later United Academy, clearly oriented toward Parisian models—such as the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture and the École Royale Gratuite de Dessin—established international networks as well as new educational principles and thus significantly garnered the interest of students from different parts of the world. These students were, at that time, coming from England, Russia, the Balkan region, North Africa, and the Kingdom of Kongo. It seems that geographical and cultural diversity combined with the interests and social ties of individual professors and members was one of the distinctive signs of the academy. At the same time, the presence of women among the regular students, together with regular and honorary members, expanded the range of people who could experience its milieu firsthand.

During my stay at the Center, I developed a crucial part of my project: the chapter focused on gender, race, and human bodies in the context of artistic academies in Vienna. In particular, it concerns the question of women at the academy, connecting my earlier archival findings within the broader context of the situation in German-speaking countries and France or England. I also tried to reconstruct the institutional identities of Viennese academies, which helped me unravel the impact of the abovementioned social and cultural changes. For this purpose, I mostly used individual reception pieces, descriptions of academic ceremonies from period newspapers and journals, and other information from primary sources. From these materials, it seems very clear that during the Engraving Academy’s existence, women played an important part in its identity. Schmutzer’s experience in Paris led him to believe in the advantages of a diverse setup. Therefore, he tried to reach out to women of different social classes and professions, who served as influential supporters, academy members, and students.

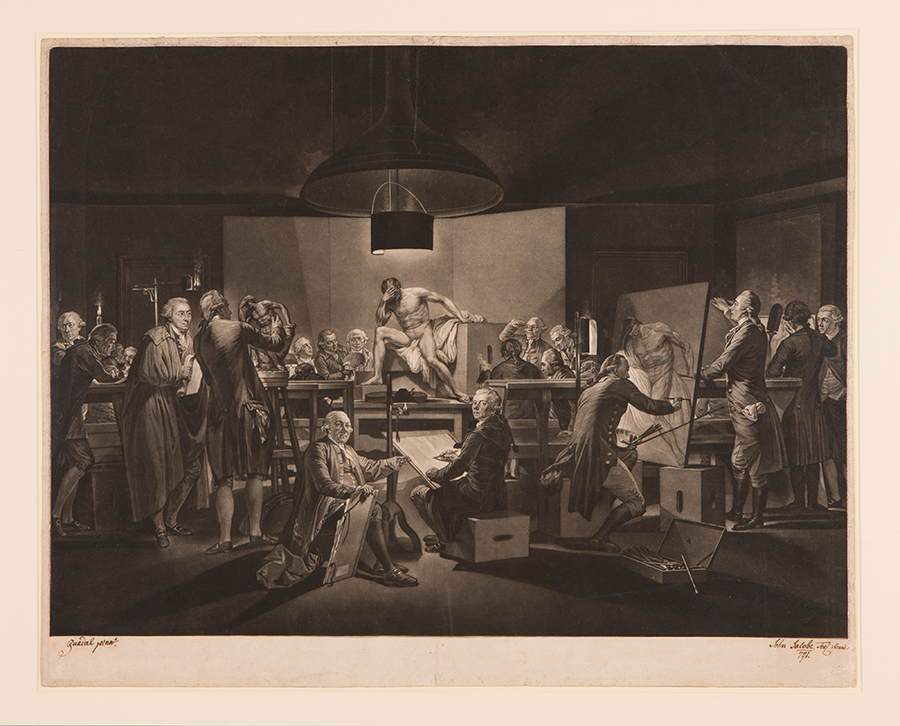

Johann Jacobe after Martin Ferdinand Quadal, The Life Class of the Vienna Academy, 1790, mezzotint on paper, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 2003, 2003.477

Much more visible “traces” were the reception pieces and gifts of female artists permanently on view at the academy, and seen next to the artworks of their male counterparts. In addition to works by the abovementioned dilettantes or amateurs, there were also examples by professional and internationally recognized female painters as well as regular members of the academy, such as Anna Dorothea Lisiewska (Therbusch) or the now almost forgotten Gertrude Cornélie Marie de Pélichy. Therbusch painted a bold variation of Artemisia Drinking the Ashes of Mausolus for the academy. Pélichy, by contrast, chose the theme of Caritas Romana, which she made after the famous painting by her teacher Jean Jacques Bachelier. Both paintings were intended for the male gaze of the official members but also showed a high level of self-confidence among the female artists, who were then developing their own strategies for success in a field dominated by men.

Although these clues and traces symbolize women’s “silent presence” in the academic environment created by Schmutzer, they are also the first signs of institutional changes—ones that were not fully realized at the Vienna academy until the first quarter of the 20th century.

Masaryk University and Czech Academy of Sciences

Beinecke Visiting Senior Fellow, June–August 2023

Tomáš Valeš will return to his positions as assistant professor at Masaryk University in Brno and researcher at the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague, where he will finish the manuscript for his forthcoming book.