Susan B. Wertheim

Contemplative Spaces in Modern Architecture

Modern architects use essential elements to create space and to connect people with the natural world through our human sensibilities. In this study of programmatically simple but spatially rich contemplative places, I see how the elements and principles of modern architectural design intersect with the five elements of the natural world—earth, wind, fire (light), water, and atmosphere (outer space, cosmos)—and how in turn these elements might appeal to our five senses. Indeed, some modern sacred spaces resonate in a deeply profound way without relying on the constructs and iconography of traditional religious architecture. In a quest to know more about how these modern spaces resonate with people and engage our senses, I reconnected with my early grounding in the design principles and theories of modern architecture and posed a series of questions: Is what we consider “sacred” evident in modern contemplative spaces? Can a place that is simple and abstract be transcendent? How do these spaces make us feel and why? I wanted to keep this research experiential, more direct, and less academic.

I proposed to focus on small secular chapels and sacred spaces, nondenominational chapels, artists’ chapels, some architectural memorials, and a few religious spaces. I wanted to look at how these places connect with people and then prepare a comparative analysis of a few select works. After establishing a basic framework for this study, with definitions of terms and concepts, I planned to travel to two or three locations to test out my initial thoughts and theories against reality, and to experience these spaces firsthand.

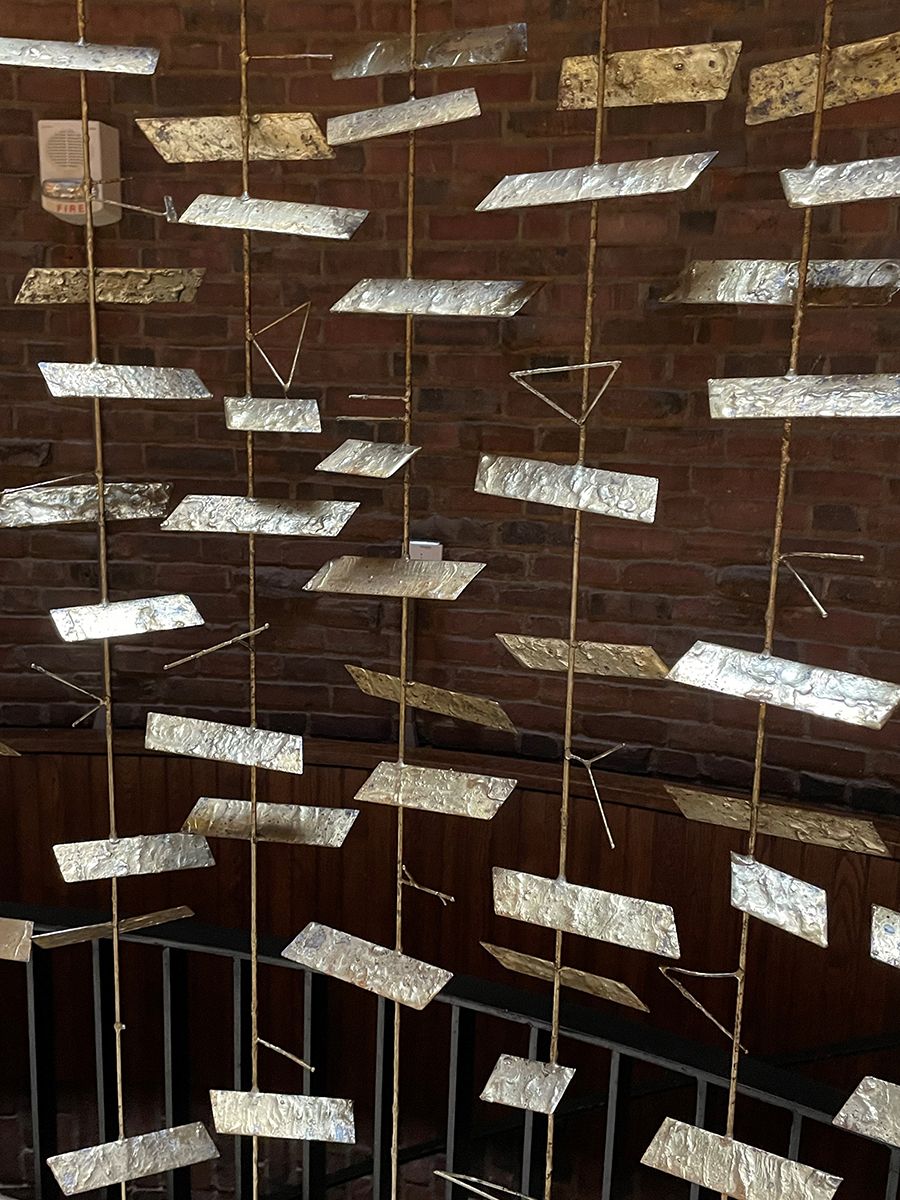

Eero Saarinen, MIT Chapel, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, 1955, with Harry Bertoia, Untitled (altarpiece or reredos), 1955, brazed steel. © 2024 Estate of Harry Bertoia / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Susan B. Wertheim

As a professional who is steeped in hands-on problem-solving, I refreshed my grounding in the more theoretical aspects of architectural design. I embraced the concept of “being-there” or “être-là,” which I discovered in Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space. Spaces built solely for the purpose of thinking, contemplating, meditating, and retreating into a more spiritual zone are not as rare as I initially expected. As the typological list of spaces to consider grew, I decided to narrow the aperture of my lens and only visit a handful in the United States and Japan. To date, I have visited Eero Saarinen’s MIT Chapel in Cambridge, Massachusetts, along with Pietro Belluschi’s First Lutheran Church of Boston and Louise Nevelson’s Chapel of the Good Shepherd at Saint Peter’s Church in Manhattan. Next, I will travel to Japan and visit the work of Tadao Ando and other architects and artists at the Benesse Art Site; I. M. Pei’s Chapel at the Miho Institute of Aesthetics; as well as traditional and modern works in Kyoto, Nara, and the islands of Naoshima, Teshima, and Shikoku. These sites were selected to further explore how architects use the intersection of architecture, art, and nature to enrich contemplative spaces.

Saarinen’s chapel at MIT (1955) is a touchstone for me, which I first encountered as an undergraduate architecture student. Most memorable was the chapel’s purity, the interplay of daylight with the space, its textures and forms. The cylindrical brick chapel is tactile, inside and out. The entrance is a simple linear connector, subtly colored with handblown glass. The water of the surrounding moat reflects daylight inside, which moves and bounces off the interior, undulating clinker brick walls.

Harry Bertoia, Untitled (altarpiece or reredos; detail), 1955, brazed steel. © 2024 Estate of Harry Bertoia / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Susan B. Wertheim

The chapel’s focal point is an altarpiece (reredos) commissioned from the artist Harry Bertoia, also in 1955. This is a unity creation; the art and architecture were conceived in unison. Bertoia’s work is evident in Saarinen’s initial design renderings. Bertoia’s delicately textured screen of gilded metal refractors, strung on sheathed wires, joins the marble floor with the oculus above, drawing your eyes upward. The altarpiece passes behind a white honed marble table set on three disks of travertine, connecting the chapel’s floor to the skylight against the background of a subtly sloping black ceiling. To me, Saarinen’s space and Bertoia’s work of art are magical, uplifting, and glimmering with hope. One of my colleagues likened it to tears, maybe from heaven?

On the day of my visit, a choral group rehearsed, and practiced singing to the center of the chapel from the undulating perimeter alcoves, which I learned is called antiphony. I caught the beginning of a noontime “mass” that was truly multidenominational, somewhat impromptu, and informal. This chapel’s appeal is thus multisensory. The sensations of lightness and light in a windowless space are most memorable.

Experiencing architecture, rather than describing it or reading about it, is a luxury. Now at the midpoint of my journey, I see the transcendent ways that simple, well-designed spaces open your mind and your imagination. In the spirit of Le Corbusier’s treatise about ineffable space, these places by their nature are difficult to describe in words. Nevertheless, they have the power to communicate. These spaces don’t dictate: “Think this!” Rather they ask: “What do you think?”

Office of Architecture and Engineering, National Gallery of Art

Ailsa Mellon Bruce National Gallery of Art Sabbatical Fellow, 2023–2024

Susan B. Wertheim is the chief architect and deputy administrator for capital projects at the National Gallery of Art. In the future, she plans to share this research in an illustrated talk at the National Gallery.