Petra Trnkova

Copy Relations: The Mechanical Reproduction of Art in the Mid-19th Century

The growing interest in mechanical reproduction and replication in the first half of the 19th century affected every single aspect of human activity, from industry to commerce, administration, science, education, and entertainment. The mechanical reproduction boom also influenced the organization of artists’ and artisans’ workshops, the form of museum collections, and the furnishings of many bourgeois households. The 1830s and 1840s were a particularly fruitful period. At that time, the public learned about a multitude of mechanical reproduction techniques. In addition to ruling machines intended for copying medallions, cameos, or coins, and pantographic machines designed to manufacture replicas of sculptures, similar efforts were developed to make available cheap copies of famous paintings.

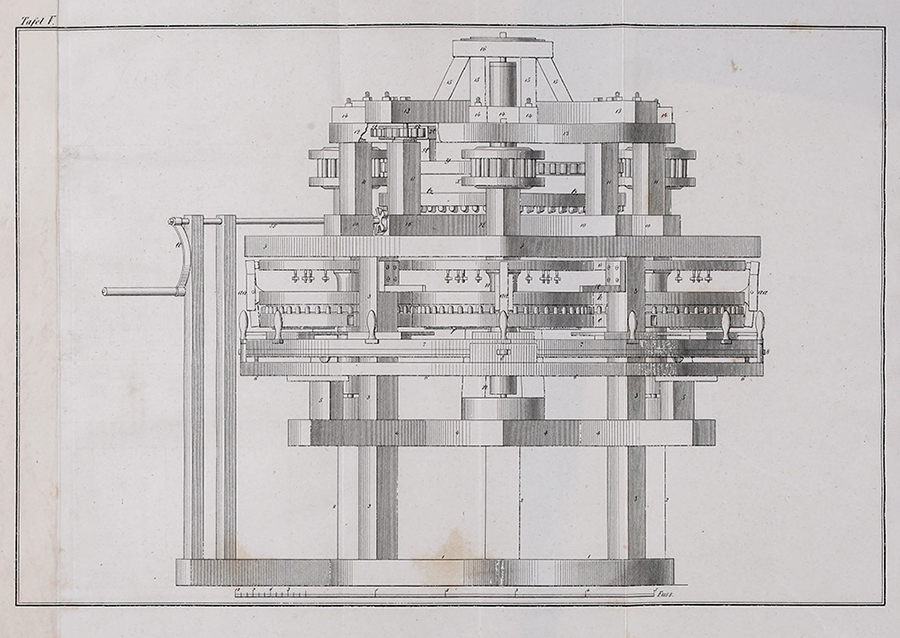

Jacob Liepmann, “Apparatus joining four small printing machines by means of which smaller sheets can be printed particularly fast,” steel engraving, from Jacob Liepmann, Der Ölgemälde-Druck (Berlin, 1842), pl. 5, Getty Research Institute

One of the most curious and now rather forgotten attempts to make the works of old masters available in the form of relatively inexpensive, fast, and faithful color replicas was the Ölgemälde-Druck—a method of printing oil paintings introduced by the Berlin painter Jacob Liepmann (1803–1865) in January 1839. It promised to supply the market with numerous printed copies of original artworks in actual size and true color that looked like oil paintings rather than color prints. The goal of the invention was to make famous artworks available to the general public, and at the same time to ease the boring and poorly paid work of copyists. The core of Liepmann’s method comprised a full-size, detailed drawn schema of the original work of art based on a study of color composition; a printing matrix made on the principle of a mosaic; and a printing apparatus. It soon transpired that the products of Liepmann’s printing machine differed considerably from the paintings on which they were modeled, and that the laborious manufacture of the color printing matrix far exceeded the hypothetical benefits of the reproduction itself. Nevertheless, some considered the invention viable for a relatively long period of time.

Liepmann’s story could be interpreted as a bizarre curiosity if countless other short-lived methods had not also appeared in the 1830s and 1840s—not only methods to reproduce oil paintings, but also other artworks and artifacts, such as the anaglyptograph, Salter Livesay’s (1810–1860) contour graphimeter, Friedrich A. W. Netto’s (dates unknown) oil painting printing, and Franz Raffelsperger’s (1793–1861) typometry. The processes were completely different, but contemporaries saw a clear analogy among them as they promised the same result: mechanically produced images or objects using an automatic, fast, and faithful multiplication of a model with zero or negligible human interference. Seen in this broad context, there is nothing bizarre about Liepmann’s enterprise; instead, he seems almost to be an essential part of it.

Jacob Liepmann, Fragment of a Printing Plate, c. 1855, Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin. Photo: Dorin Alexandru Ionita, Berlin

During my two-month fellowship, I developed a draft of an article focusing on Liepmann’s method of oil painting printing as seen in the context of other period methods of mechanically reproducing artworks and artifacts, as well as the public discussions that surrounded them. Drawing on the rich collection of secondary sources at the National Gallery of Art Library, I was able to expand my knowledge and deepen my understanding of numerous related topics, such as the pictorial representations of machines, color theory, pigment production, 19th-century artistic and scientific networks, and numerous other printing and drawing techniques. I also conducted primary-source research at the Library of Congress and the National Museum of American History. And, not least, while in residence at the Center, I benefited greatly from discussions with other fellows as well as their expertise in different topics, both related and more distant.

Although centering on the noteworthy story of Jacob Liepmann and the idea of the mechanical reproduction of paintings, my forthcoming article argues that the whole topic of mechanical reproduction in the mid-19th century is too thick to be looked at from a single point of view or through a specific method or material, and that it requires multiple and divergent points of view. We cannot possibly cover all of the methods and actors involved in these endeavors, but it would be a mistake to ignore this phenomenon and also to focus on methods according to material or the predominant direction of our discipline. The second key argument delves into the historiography of art history in general: this material, however unusual, curious, or episodic it may seem, makes us think critically about how we construct paradigms. Concomitantly, it prompts us to take into account the failures and absences that were an indispensable part of artistic processes, practices, and commerce.

Institute of Art History, Czech Academy of Sciences

Paul Mellon Visiting Senior Fellow, September–October 2023

Petra Trnkova will return to her position as research fellow at the Institute of Art History, part of the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague.