Pamela H. Smith

Socio-Natural Industryscapes in Early Modern Europe

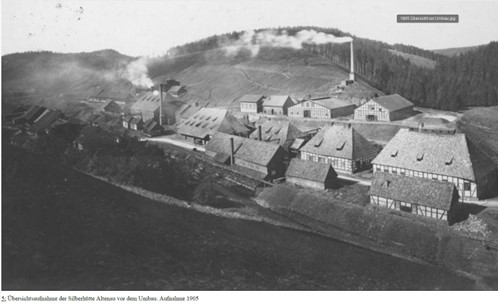

The line of simple, half-timber buildings standing on the slopes of deforested hills along a bend in the river, smoke billowing over them from the smelting ovens, is remarkably similar over 251 years.

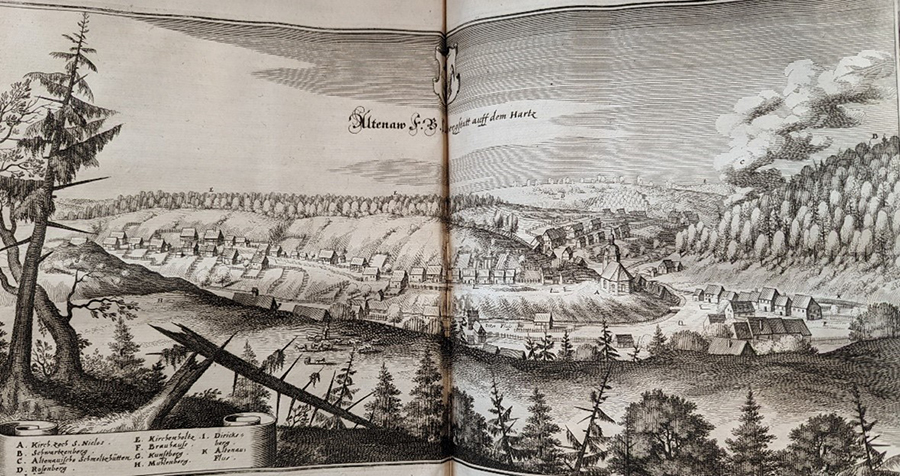

Matthaus Merian I, Topographia vnd Eigentliche Beschreibung der Vornembsten Stäte, Schlösser auch anderer Plätze vnd Örter in denen Hertzogthümern Braunschweig vnd Lüneburg, und denen dazu Gehörende[n] Grafschafften Herrschtafften und Landen, published 1654, National Gallery of Art, Mark J. Millard Architectural Collection, David K.E. Bruce Fund, 1985.61.2553

Mining towns such as Altenau can be understood as “socio-natural landscapes,” in which humans and nature are enmeshed in complex relationships. I investigate such sites to better understand the reciprocal dynamics between humans and their environments in premodern (so-called preindustrial) Europe. Building upon work by The Making and Knowing Project, which brought art and science together around the historical making of early modern objects in a lab, my present project on “industryscapes” brings together artistic and scientific representations from both the past and today to gain insight into another dimension of human relations with the natural world.

From about 1400, Europe saw rapid expansion of many industries, including mining, and, at the same time, new views emerged about the capacity of human beings to shape nature and extract its resources. In the same period, mining landscapes were an increasingly frequent subject for artists working for mine investors. By studying such industryscapes from a variety of perspectives, employing different types of evidence and research methodologies, I believe we can illuminate long-term changes in socio-natural interactions and systems of knowledge.

My investigation of socio-natural sites includes collaborations with archaeologists and environmental scientists. An initial phase of the project includes a PhD summer school, MINESCAPES: Socio-Natural Landscapes of Extraction and Knowledge in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period, that brings together students and scholars from the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences for field trips into the millennia-old mining landscape of the Harz Mountains (mined since the Iron Age), where we will study the archives of nature (forests, rivers, soils) and society (documentary records, maps, artistic representations). Through cultural-historical methods, archaeological data, and scientific analyses of soil, water, and flora, we hope to gain a more comprehensive picture of the site’s complex human-environment relationships both in the past and today.

Anonymous, Altenau, 1905

While at the Center, I conducted a preliminary and wide-ranging survey of artistic representations of industry in early modern European landscapes, which are especially rich in Topographia vnd Eigentliche Beschreibung der Vornembsten Stäte, Schlösser auch anderer Plätze vnd Örter in denen Hertzogthümern Braunschweig vnd Lüneburg, und denen dazu Gehörende[n] Grafschafften Herrschtafften und Landen by Matthaus Merian I (1593–1650). Like the other 15 volumes in Merian’s massive collection of maps, this one contains phenomenally detailed depictions of towns, mines, noble residences, and cultivated plots. The volume illustrates the territory of the dukes of Braunschweig and Lüneburg, who grew wealthy from the mineral riches of the Upper Harz Mountains, and thus provided capacious scope for Merian’s apparent abiding interest in and admiration for Kunst—the mechanical arts. His maps note with care the region’s canals, mills, fountains, smelting huts, and mines—all the industry through which humans terraformed the earth and transformed its resources. At the same time, his illustrations make evident the destructive extraction processes of mining: the bare hills, the poisonous metal smoke that covered all, and the maladies suffered by miners and smelters.

Which of these contrasting views did Netherlandish painters of the 16th and 17th centuries intend to convey through their many, but obliquely presented, details of human industry? See, for example, Martyrdom of Saint Catherine, in which Catherine’s martyrdom takes place in the far distance, whereas in the foreground men are harvesting wood, something that occurred across Europe for every conceivable use, from building, heating, and smelting to—if we follow the course of the woodsman’s path—the building of ships. The painter portrays a cycle of growth that merges with human use. Many such landscapes from the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly by Netherlandish painters, portray “resource extraction” and the industries that rely upon it by foregrounding the activity, though not as the painting’s subject.

My research at the Center left me with questions that I will continue to pursue both in landscape paintings and in the MINESCAPES summer school. Can we detect a discontinuity in the way that early modern European observers perceived and responded to “nature,” perhaps especially in longue durée sites of intense human activity, such as “minescapes”? Amitav Ghosh argues in The Nutmeg’s Curse that Europeans, at the helm of global capitalism and colonization, began to view the “world-as-resource.” Do representations from this period, whether artistic, scientific, or cartographic, reveal a changing relationship between human beings and their environment? In what specific ways are these Netherlandish landscapes, with their somewhat oblique and misdirecting focus on human art and industry, a byproduct of expanding European capitalism and colonialism in the early modern period?

Columbia University

Edmond J. Safra Visiting Professor, spring 2024

Pamela H. Smith will travel to Wolfenbüttel, where she will receive the international Wissenschaftspreis for Cultural History and the History of Knowledge from the Herzog August Bibliothek and the Hans und Helga Eckensberger Stiftung. She will colead the MINESCAPES summer school there and, in the fall, return to Columbia University to resume teaching.