Nancy J. Troy

Making History: Architectural Models and De Stijl

Architectural models have always been central to the history and the historical construction of De Stijl. The project I launched at the Center seeks to understand the roles played by architectural models, particularly (but not exclusively) those that have been made after the fact, whether first-time constructions or reconstructions of lost originals. My aim at this initial stage of the inquiry is to explore how questions of authenticity, originality, and reproduction have played out across the century since De Stijl emerged in 1917. What is the nature of the original objects and how are they represented in historical documentation? What is to be gained and what might be lost when reconstructions proliferate? And why do audiences seem to desire these ersatz interventions? Can we learn something about this from the attractions of virtual reality as new technology enters what Tony Bennett referred to as the exhibitionary complex and impinges on the experience of works of art?

Frans Postma, Scale model of Piet Mondrian’s studio at 26, rue du Départ, Paris, 1926

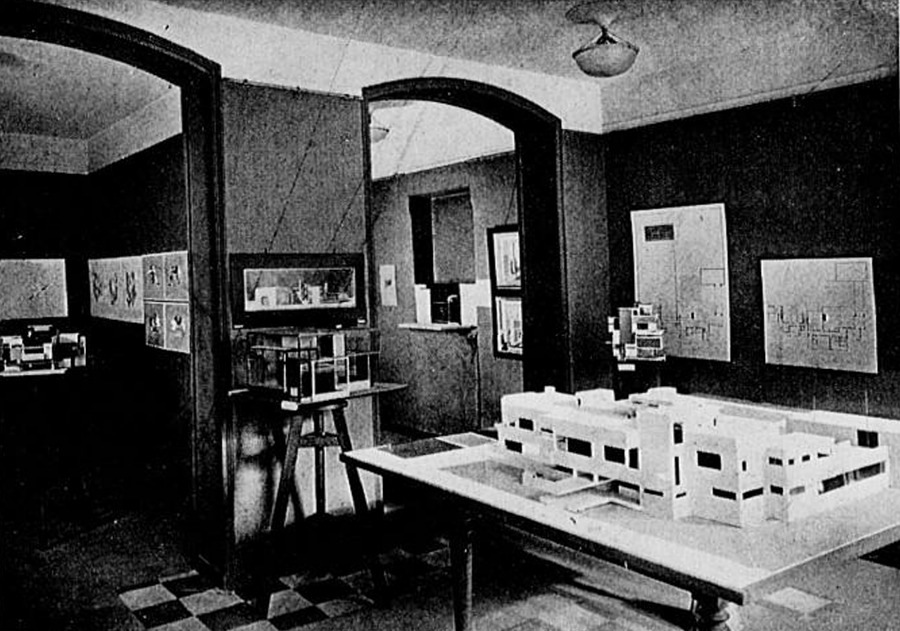

The first exhibition devoted to De Stijl as a group opened in October 1923, not in the Netherlands, where the eponymous journal had been founded six years earlier, but in an art gallery in Paris. Focused exclusively on architecture, Les architectes du groupe ‘de Stijl’ (Hollande) featured 52 exhibits ranging from plans, elevations, and models of unrealized designs to photographs of recently completed buildings and individual interiors. It showcased the participants’ vision of a radically new approach to spatial form in which color would be not just applied to the walls of a building but deployed as planes in space, offering a new, potentially revolutionary experience of the built environment. Especially influential were models for a Private House as well as a House of an Artist designed collaboratively by Cornelis van Eesteren (1897–1988) and Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931), and a series of colored axonometric projections extrapolated from these models. Ironically, however, the influence of these objects was due less to the display of the originals than to their illustration two years later in the deluxe French journal, L’Architecture vivante. In the meantime, while stored in the basement of the publisher’s offices, the models suffered irreparable damage and were discarded.

Unknown photographer, Installation view of Les architectes du groupe ‘de Stijl’ (Hollande) (October 15–November 15, 1923), Galerie L’Effort Moderne, Paris

Given the groundbreaking significance of the 1923 models in the history of De Stijl and modernist architecture, it is not surprising that the organizers of the first exhibitions to examine the group’s legacy would wish to re-create these highly resonant objects for shows at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1951 and the Museum of Modern Art in New York the following year. However, the surviving architects, well aware that these first historical shows would impact the current reception of their work, could not agree on crucial curatorial questions, including whether to authorize the re-creation of the models. What thus emerged from the organizing process was a struggle over the shape that the historical construction of De Stijl would assume. At the same time, numerous reconstructions of iconic De Stijl furniture designs were made for these shows and subsequently entered museum collections, where the distinction between original and copy was strategically ignored, or at least obscured. When a blockbuster exhibition of the early 1980s devoted attention to the many De Stijl interiors designed by the movement’s affiliates, few of which were still extant, there was a desire to construct them as scale models ranging from tabletop objects to life-size environments that amounted to an immersive visitor experience, one that could be instructive even if rather obviously artificial—a period room in modern style. For my purposes, the most ambitious examples are models of the studios of Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) in New York and Paris. The latter, including one at full scale, has been intensively researched and extensively displayed by Frans Postma, who now plans a virtual-reality version.

As this report was being written, I was days away from a trip to the Netherlands during which I would consult the holdings of numerous museums and archives, and conduct interviews with a few key figures in the story I seek to tell. This research should enable me to ground the work I have done during my year at the Center in resonant case studies, and provide a basis for developing the project into a publication that contributes to the understanding of how history creates meaning for its audiences, and vice versa.

Stanford University

Kress-Beinecke Professor, 2023–2024

Nancy J. Troy will be splitting her time between her home in the Bay Area and Washington, DC. From those bases, she plans to pursue her project initiated at the Center.