Molly Superfine

(Re)Casting History: Ruination and Remembrance in the Early Works of Beverly Buchanan, 1972–1981

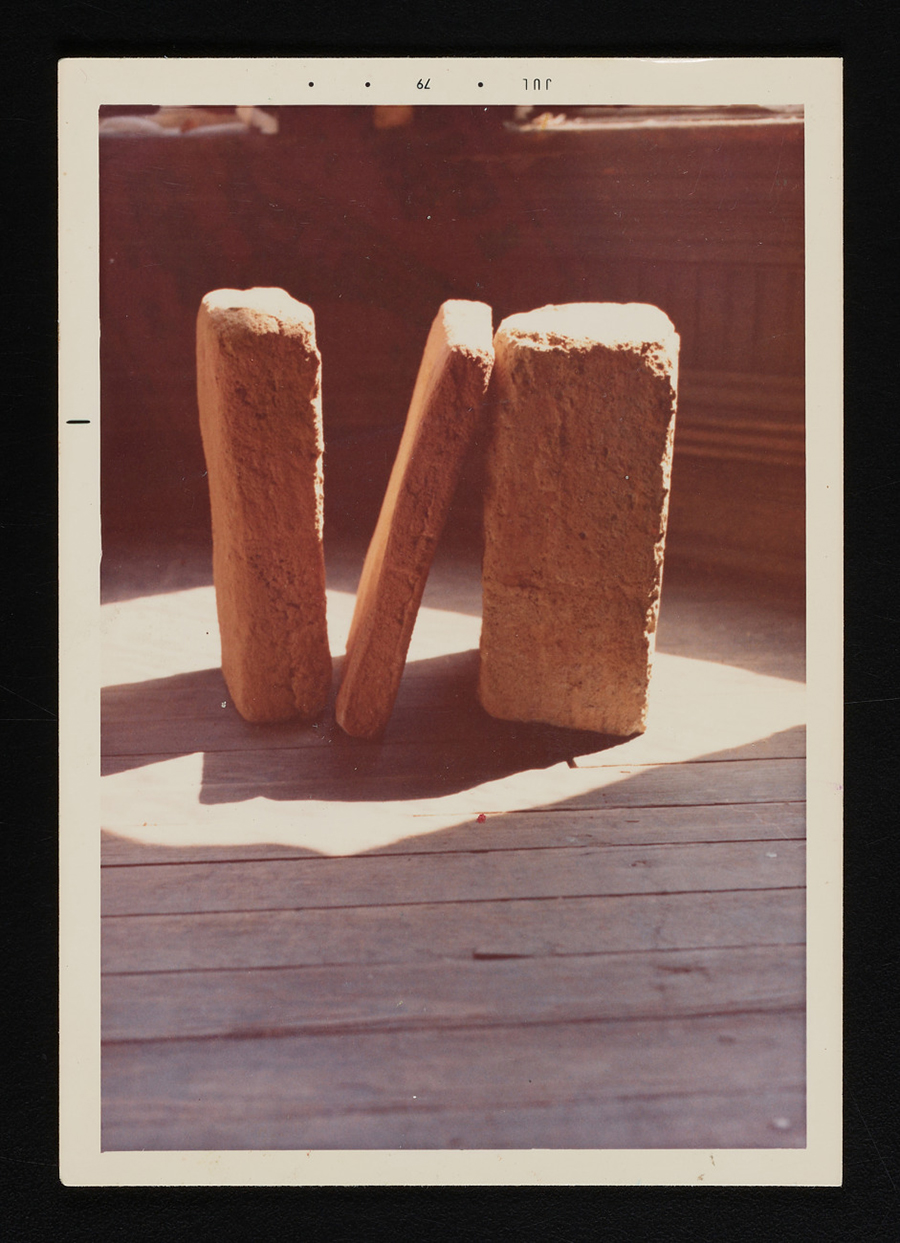

Unidentified photographer, Frustulum by Beverly Buchanan, July 1979, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Beverly Buchanan papers, 1912–2017

Since my arrival at the Center in October 2023, my research has focused on moving my doctoral dissertation “Ruins and Remains: Performative Sculpture and the Politics of Touch in the 1970s” (2023) forward into article-length papers and, eventually, a book manuscript. I am currently doing a close dive into the artist Beverly Buchanan (1940–2015), her extensive training in health sciences, and how this expertise was inflected in her artistic practice. Buchanan received her master of science in parasitology in fall 1968 and her master in public health in summer 1969 from Columbia University, and her journals reveal a lifelong concern regarding the health of Black children, girls in particular. I have spent time in the archives of the Columbia University Irving Medical Center and will embark on a road trip throughout the artist’s home state of Georgia this spring to locate her sculptures in situ. Buchanan’s works take their forms from southern vernacular and domestic architecture, but my current research pushes this reading of her work further, toward excavating the very condition of those who occupied these architectures. Buchanan’s early Frustulum series (1978–1981) is of main concern: these works are tabby concrete castings in the shape of rectangular slabs and natural boulders. Tabby concrete, a compound binding agent made of sand and lime, is a localized, inexpensive material that was often used by enslaved people in the southern United States, especially in coastal states like Georgia with access to massive deposits of lime-rich oyster shells. The artist takes surface imprints of shotgun houses and other domestic constructions and transfers the textures to her sculptures. In this way, Buchanan activates positive and negative spaces to interrogate the fraught relationship between nature and laboring bodies. Her pieces are placed either in art institutions or in nature, to be subsumed by grass and moss. Engaged equally with the power of memory as well as its proclivity toward fragmentation and negation, Buchanan memorializes both the legacy and the labor, physical and otherwise, of Black women in the antebellum South.