Meghaa Parvathy Ballakrishnen

Untitled: Nasreen Mohamedi, Geeta Kapur, and Art History’s Time

Nasreen Mohamedi, Untitled, 1975, ink and graphite on paper, 24.1 × 24.1 cm, Sikander and Hydari Collection

Over the last two years, I have been braiding paths between two Indian women. Nasreen Mohamedi (1937–1990) was an abstract artist born in Karachi (now in Pakistan), who lived, worked, and taught in South Asia, the United Kingdom, Bahrain, and France, and who traveled extensively in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, synthesizing the historical avant-garde with Indo-Islamic aesthetic theory to sustain a decades-long vocabulary of lines, planes, vectors, and arcs. Geeta Kapur (b. 1943), a self-designated “historian-critic,” was born in New Delhi and has lived and worked in South Asia, North America, and Europe, developing through the second half of the 20th century strategies with which to reconcile the Indian nation-state with world modernism. She emphasized, in particular, the role the represented human figure, as a grounds for social identification, should play in this effort. Parallel paths, it should seem; and yet.

From 1990 to 2016, mourning both her friend and the death of the secular nation, Kapur drafted two extended essays on Mohamedi’s practice, “Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved” and “Again a Difficult Task Begins,” that offer us a reassessment of her critical project. Periodizing modernism toward a new history of avant-garde practices, with Mohamedi as an anchor, these texts skim aesthetics, craft, theories of aesthetic labor, and a “re-enchantment of the secular,” to disclose a radically transhistorical poetics. I use this pivot to offer, first, a new reading of Kapur’s criticism, including interpretations of two major, somewhat misunderstood, texts, “Partisan Views about the Human Figure” (1981) and “When Was Modernism in Indian/Third World Art?” (1993). Second, against their poetic weight, I historicize Mohamedi’s untitled works—self-portraits in the 1950s; prints, landscapes, and “automatic” watercolors in the 1960s; allover ink drawings in the 1970s; and optical diagrams in the 1980s—as serial material investigations. I demonstrate the remarkable range of her aesthetic resources for such attentive duration, which include weaving, music, poetry, metaphysics, the ocean, the desert, architecture, and urban planning, and situate her abstraction as an “artisanal” practice translated to the seriality, anonymity, and procedural innovations (print, drawing, collage, and montage) that characterize art after capitalism.

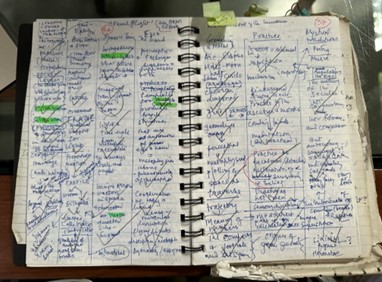

Geeta Kapur, Nasreen Notebook, 2010s, from her personal archive © Geeta Kapur

Five chapters meet Kapur and Mohamedi at conceptual and historical intersections. In the first, “Double Self-Portait,” I develop Mohamedi’s early self-portraits and their relationship to Kapur’s theory of the citizen-subject in “When Was Modernism?” The second, “Nature,” situates Mohamedi’s prints, landscapes, and automatic drawings from the 1960s as a material quest for immersion in deep time, as against Kapur’s theory of recognition, embedded in readings of Négritude, in her 1968 essay “Quest for Identity.” The third, “Artisan,” explores Mohamedi’s abstraction in the 1970s as the revival of parallel artisanal practices such as weaving and Hindustani music, and the centrality of their ritual time to Kapur’s reevaluation of abstraction as an embodied labor, theorized through Bhakti poetry, in her 2016 “Again a Difficult Task Begins.” The fourth, “The Binding,” draws out the phenomenological experience of viewing Mohamedi’s abstraction, as well as its effects in Kapur’s writing, establishing the ethically reciprocal labors both critic and artist solicit. In the fifth, “History,” I outline Kapur’s theory of narrative figuration in her “Partisan Views on the Human Figure” and contrast it to the corporeal departures of Mohamedi’s late drawings. Throughout, I use Kapur/Mohamedi as a model to understand the consolidation of “Indian” art history, as well as to write a history of untitled abstract art by a range of 20th- and 21st-century practitioners.

Emphasizing material, procedural, and phenomenological accounts of works of art and criticism, and drawing on extensive archival research, I bring Mohamedi and Kapur together to position abstract art as inseparable from art history’s time. By this I mean three things: the time of artistic labor (looking, making, creating, beholding, etc.); abstraction’s contingence on a long history of art and aesthetics (in its regional sense as “South Asian,” “Islamic,” “third-world,” or “Asian”; in its philosophical sense as “Indo-Islamic”; and in its temporal sense as “modern,” “contemporary,” “postcolonial,” or “avant-garde”); and the coincidence of abstract art and art history’s disciplinary consolidation.

During my research year, I was especially fortunate to have spent several days with Kapur and her personal archive of notebooks and postcards and books and correspondence, a subterranean history of abstraction locked away in trunks, punctuated by extended interviews over cups of tea: I reproduce here a snapshot, a tabulation of all the realms Mohamedi’s art stretches, with deep gratitude for our time together.

Johns Hopkins University

Andrew W. Mellon Fellow, 2022–2024

In 2024 Meghaa Parvathy Ballakrishnen will begin a postdoctoral appointment with the Society of Fellows at the Alexander Grass Humanities Institute, Johns Hopkins University, and the offices of the Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director and the Eddie C. and C. Sylvia Brown Chief Curator at the Baltimore Museum of Art.