Maria Gabriella Matarazzo

Beyond “Buon Fresco”: Experimenting with Oil in Early Modern Mural Painting (c. 1500–1650)

During my first year at the Center, I developed my current book project, titled “Beyond ‘Buon Fresco’: Experimenting with Oil in Early Modern Mural Painting (c. 1500–1650),” the first monograph dedicated to the use of oil binders in wall painting of the Italian Peninsula. One of the most persistent (and in some ways misleading) ideas inherited from Renaissance art theory is the assumption that every mural of the period was painted in fresco—that is, pigments mixed with water applied on freshly laid plaster—to the point that often the term “fresco” is still used as a synonym for “mural” today. The roots of this (mis)conception can be traced back to Giorgio Vasari’s Lives (1550 and 1568), whose introduction, the Teoriche, fervently praises fresco technique—to this day considered one of the foundational passages in the Italian Renaissance theory of art. There, Vasari describes fresco as the “most certain, most resolute and durable” technique for wall painting. In recent decades, however, extensive restoration campaigns have proved that in the early modern period the techniques and materials of mural painting throughout Italy were far more heterogeneous than the monolithic image of true fresco (or “buon fresco”) advocated for in the Teoriche, even more so considering that mixing fresco and secco techniques was common practice. Drawing from this scientific evidence, my project casts light on how many early modern painters, dissatisfied with the hard-edged quality of fresco and the light color palette it produced, turned to other binders—particularly oil—in search of a medium more compatible with their stylistic intentions, despite its greater perishability once applied on the wall.

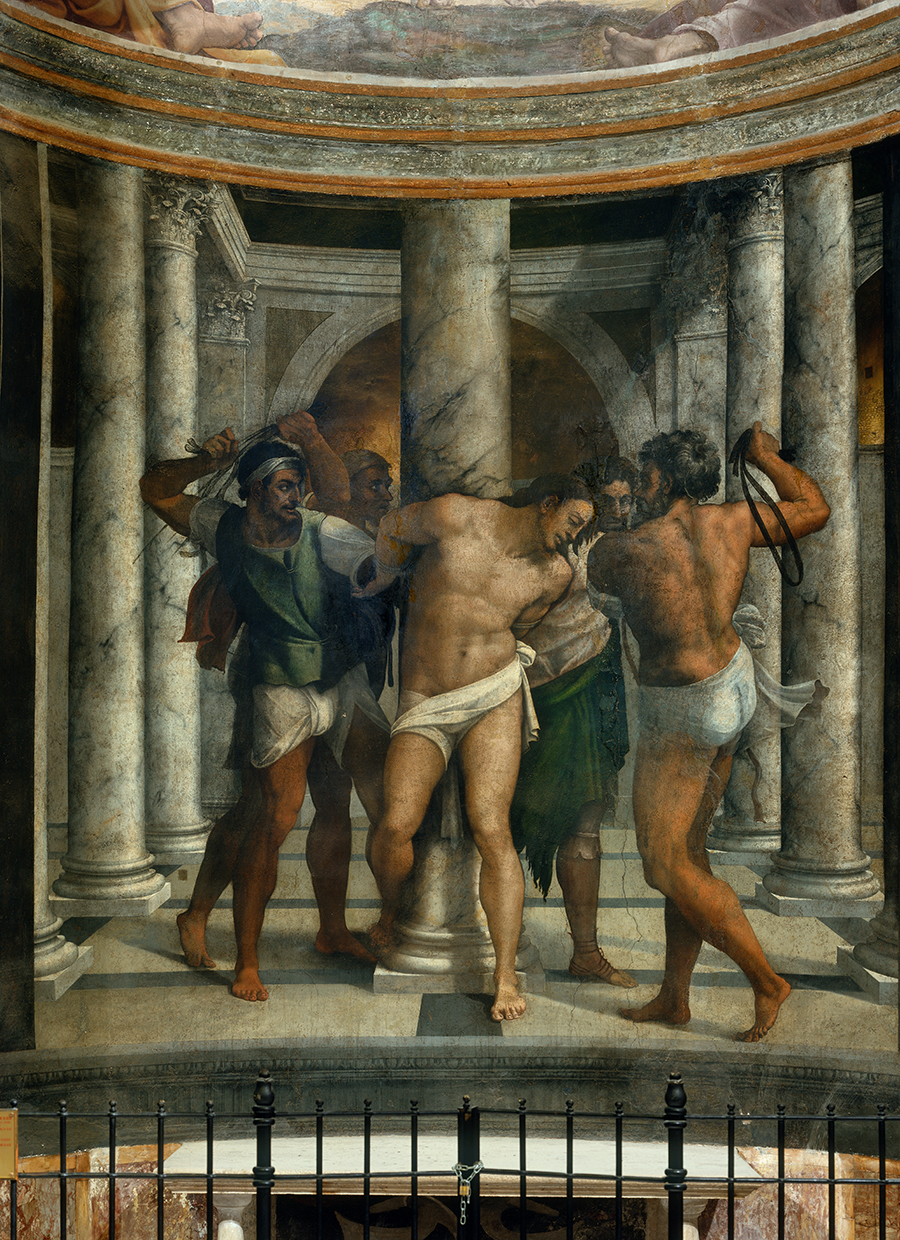

Sebastiano del Piombo, The Flagellation of Christ, 1516–1524, oil on plaster, Borgherini Chapel, San Pietro in Montorio, Rome. Photo: Scala / Art Resource, NY

While data from restorations and laboratory inspections indicate that the practice of oil-on-wall was far from episodic, little has been done in art-historical scholarship to systematize the scattered evidence and situate it within a historical and critical framework. My book aims to fill this gap and intends to demonstrate the role that this overlooked and little understood mixed technique played as a site for experimentation and innovation in Italian Renaissance and baroque painting.

Beginning with Leonardo da Vinci’s explorations of the medium in the Last Supper and (according to Vasari) the lost Battle of Anghiari, my book explores the cultural and formal reasoning behind the adoption of this experimental and fragile technique of mural painting with oils. From Raphael and Sebastiano del Piombo to Caravaggio and Guido Reni, many early modern artists painted with oils on walls, the history of which I trace in my book. In particular, I examine the preference of artists from different generations for oil painting on wall over fresco to give shape to their distinctive styles and narrative intentions, despite the material instability and perishability of the medium. Central to my project is thus an assessment of the affordances of the oil medium, with a decisive shift in focus from easel painting (as has been proposed in previous studies) to murals. The oil medium, unlike fresco, provides slower drying time, a deeper range of tones, and consequently the ability to better express values of naturalezza (naturalism), morbidezza (tenderness), and unione (harmony of tonal ranges)—allowing painters to push the boundaries of “the wall.” Therefore, my project explores the relationships between the material agency of oil paint, technique, and style, and suggests framing the adoption of oils in the realm of wall painting as an undercurrent of naturalistic tendencies in early modern art.

Caravaggio, Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto, c. 1599, oil on plaster, Casino Boncompagni Ludovisi, Rome. Photo: Scala / Art Resource, NY

The Center has provided me with critical resources to advance my book project. The institute’s location in the National Gallery of Art, with its exceptional art collection, allowed a close examination of a number of oil paintings produced by key figures in my project (e.g., Leonardo, Raphael, Sebastiano). In addition, my frequent exchanges with the National Gallery’s conservation division greatly enhanced the technical aspects of my project. Finally, the multicultural and interdisciplinary dialogue within the Center’s community of scholars has allowed me to engage with a broader, global history of wall painting. These conversations have exposed the enduring and cross-cultural afterlife of certain nodes of Renaissance art theory—as we see, for example, in the idea of “buon fresco” as the mural technique par excellence and its impact on Diego Rivera and Mexican muralism in the 20th century.

Washington DC

Beinecke Postdoctoral Fellow, 2023–2025

During the forthcoming 2024–2025 academic year, Maria Gabriella Matarazzo will spend her second year at the Center as the Beinecke Postdoctoral Fellow.