Margaret L. Laird

Drawing Beasts in the House of the Cryptoporticus at Pompeii: Narrativity and the Ancient Roman Imagination

A beast hunter stabs a bear with a lance as the animal fights back. Thin “action lines” that emanate from the bear’s claws convey his attack. Late second/early first century BCE–62 CE, graffiti drawing on fresco, south wall of oecus 22, House of the Cryptoporticus (I.6.2), Pompeii. Photo: Margaret L. Laird, su concessione del Ministero della Cultura—Parco Archeologico di Pompei

Drawings constitute a large but virtually untapped body of evidence for ancient Roman culture. These images survive in different media: as graffiti on walls in public, private, and commercial spaces; as figures incised on lead curse tablets; as sketches inked onto papyrus; as marks made with metal point, ocher, and charcoal; and as outlines painted with brush and monochrome pigment. Most were rendered by ordinary, nonprofessional draftspeople with varying levels of artistic competence, whose identities are unknown. The images are made in a spontaneous, immediate style that is markedly independent of elite or state art. Often considered crude or simple, drawings have been undervalued as a source for understanding the ancient world.

My book project understands these figures as artifacts of visual thinking—individuals’ efforts to make visible a facet of their reality—and as evidence of physical, spatial, and temporal social practices (what I refer to as drawing events). I examine not only what Romans drew but also how, when, and where they made images. My methodology is informed by studies of Latin textual graffiti and popular culture, which have enriched our understanding of non-elite expression and visuality. Examinations of figural graffiti from other cultures and periods (especially the Maya) model ways to deal with the drawings themselves. Research by developmental and cognitive psychologists, art educators, and art theorists provides ways of understanding drawing as a culturally specific social activity rooted in perception, memory, and imagination. My book will fill a significant gap in the field of ancient art history and will expand the ancient Roman art canon.

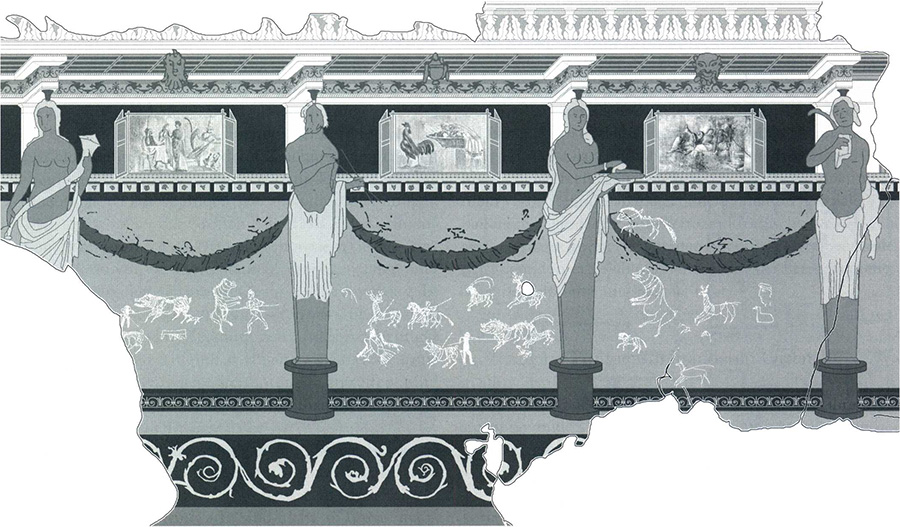

My fellowship at the Center gave me time to focus in depth on an extensive assemblage of figural graffiti made on the walls of a subterranean room (oecus 22) in the House of the Cryptoporticus in Pompeii (I.6.2). These images underpin a chapter exploring the drawing event, and feature in chapters examining the reception of elite iconography and the transmission of local and regional drawing styles. The figures were etched into the frescoed plaster on the north and south walls of the room sometime between the late second/early first century BCE (when the frescoes were composed) and 62 CE (when the room was abandoned following an earthquake). The south wall alone features more than 30 full or partial figures, ranging in height from circa 5 to over 15 centimeters. Most of the drawings depict venationes (beast hunts in the amphitheater), with animals facing human opponents on foot and horseback. This was a favorite subject among Pompeii’s drawers, and the native Italian animals depicted on the south wall suggest that the compositions reflect memories of actual events. Nonetheless, the makers of these figures relied on established visual schemata from other media and a popular understanding of excellent and dramatic fighting moves.

Facsimile drawing by Martin Langner of the south wall of oecus 22, House of the Cryptoporticus (I.6.2), Pompeii, from Antike Graffitizeichnungen (Wiesbaden, 2001), fig. 56. Courtesy of Martin Langner

Given time to carefully study photographs I had made in Pompeii in 2019, I detected several figures that had not been previously recognized and identified the “hands” of at least nine different drawers. The images show how more proficient draftspeople shared compositional tricks and techniques with their less competent peers, and demonstrate the acquisition of drawing skills through repetitive practice. By analyzing the arrangement and quality of lines, I reconstructed the order in which many figures were assembled and identified “action lines” that express movement, dramatize attack, or convey flowing blood. These details suggest that some of the figures were composed during episodes of graphic-narrative storytelling, a form of drawing identified by art educators that accompanies and motivates the creation of storylines derived from a drawer’s imagination. Some of the fighting pairs in oecus 22 are collaborations: two people rendered one “character” each in the contest. This suggests that a verbal narrative exchange accompanied image-making, as drawers acted out their roles as they composed. Elite art produced by professionals (such as mythological scenes or depictions of battles) also provided ancient Romans with opportunities to spin narratives. But these expositions were inspired by completed compositions and showcased the teller’s knowledge. In oecus 22, the making of the imagery dramatized the story as it was being created. Through graphic-narrative storytelling, the drawers embodied the spectacle’s protagonists: beast hunter, animal victim, and the organizer of the games (a role normally restricted to an elite magistrate). The drawings thus shed light on the ancient creative and empathic imagination.

As an art historian who teaches in a language department, I found it especially invigorating to be in residence among colleagues focused on the visual arts. I thank all at the Center for their intellectual generosity.

Wilmington, DE

Paul Mellon Visiting Senior Fellow, January–February 2024

Margaret L. Laird will return to the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at the University of Delaware.