Kathryn Blair Moore

The Other Space of the Arabesque: Italian Renaissance Art at the Limits of Representation

The Madonna and Child by Giotto (c. 1265–1337) is one of the most important examples of early Italian Renaissance painting in the collection of the National Gallery of Art. Giotto’s emphasis upon the modeling of the mass of Mary’s body and the intimate caress that humanizes the Queen of Heaven’s relationship to her son have long been highlighted as innovations associated with the Renaissance movement. A closer look will reveal a continuous golden script along the border of Mary’s blue robe and incised into the gold ground at the borders of the panel. The script resembles Arabic, yet the resulting letterforms do not cohere into legible phrases or sentences. Such nonsensical representations have traditionally been called Kufesque, referring to Kufic, the earliest form of Arabic calligraphy. Kufesque elements in Italian Renaissance painting have most often been regarded as ornamental play that evoke sacred scripts without precise meanings or even identifications. This conceptual ambiguity is reflected in the more recent terms used for Kufesque: that is, Arabic pseudo-script or, simply, pseudo-Arabic. Related generalizations about “Islamicizing ornament” reflect assumptions regarding the inherently ornamental character of Islamic works of art, which—the implication is—can be transposed to a new cultural context for purely aesthetic reasons.

Giotto, Madonna and Child, c. 1310/1315, tempera on poplar panel, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1939.1.256

Yet, upon closer inspection, the Arabic elements of Italian Renaissance painting are suggestive of a more significant dialogue with the figural subjects. My project involves exploring the ways in which Arabic scripts were integral to the representation of the royalty and wisdom of the Virgin Mary, and how this related to both translation and conversion movements that sought to assimilate Arabic philosophy and Islam within the Latin Christian culture of Italy. I suggest that we regard Kufesque elements of Italian altarpieces within complex spaces of cultural encounter and translation in order to form a more nuanced historical understanding of perceptions of distinctions between the image culture of figurative European art and the supposedly nonimage culture of Islamic art.

My exploration of pictorial adaptations of Arabic scripts in an Italian context is part of a larger project that seeks to reframe our understanding of the historical relationship between the arts of the Italian Renaissance and the Islamic world. At the center of the project is the concept of arabeschi, or arabesques, a term first coined in 16th-century Italy. The term arabeschi is suggestive of an act of adaptation from Arabic, in a way conceptually parallel to an imitation of Arabic scripts undertaken without understanding of linguistic content. My project entails posing the fundamental question of how the term arabesque related to Italian perceptions of Arabic writing and related arts of calligraphy, especially as perceived in contrast to the measured architecture of Latin block letters. This is part of a larger question of how the reception of the Arabic language and related artistic forms connected to—and differed from—the period’s central revival of ancient Greek and Roman artistic techniques.

Graphic tracing of the halos and pseudo-Kufic lettering in Madonna and Child. Photo: Joanna Dunn, National Gallery of Art

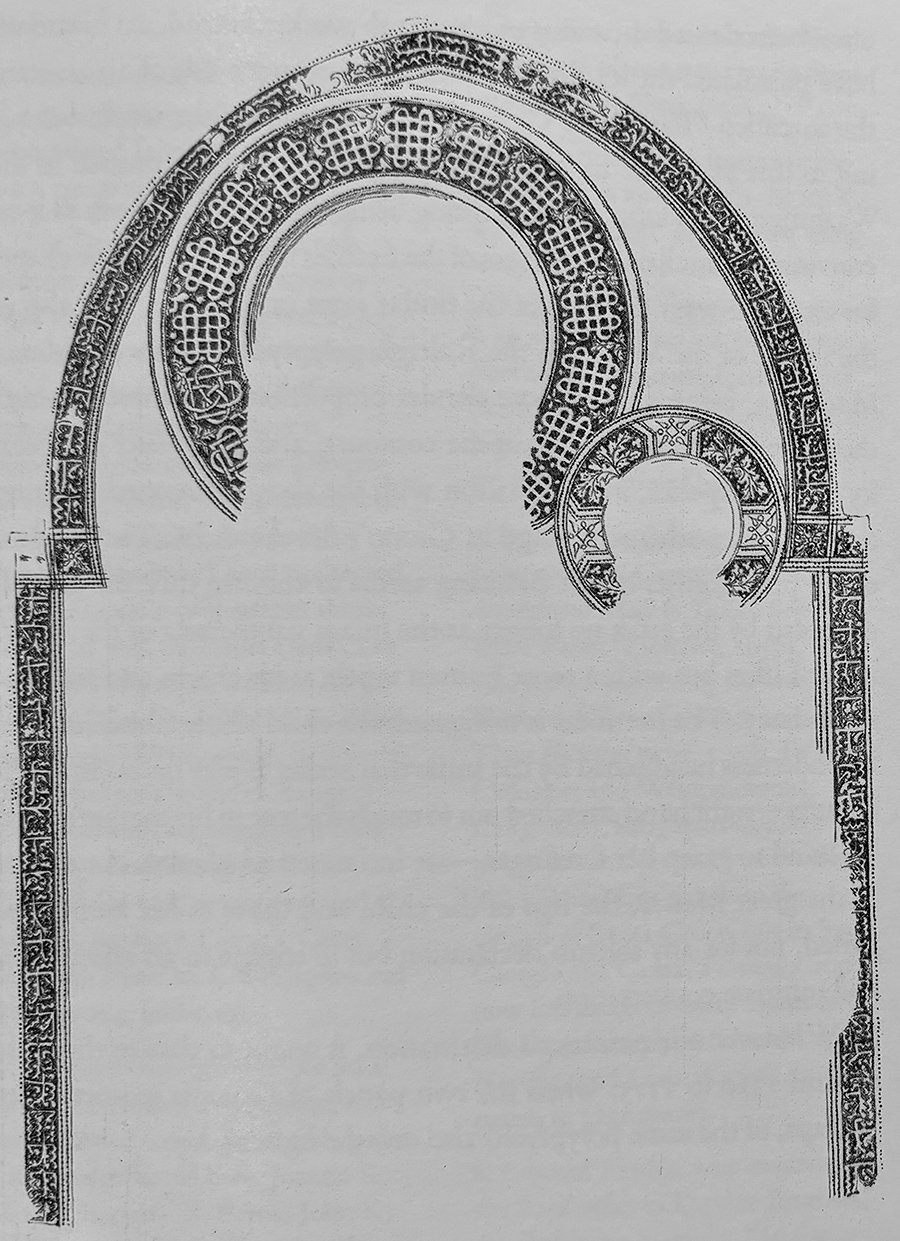

Rather than regarding arabesques as ornamental motifs passively copied by Italian artists, I argue that the creation of arabesques as autonomous printed patterns in the 16th century should instead be understood as the culmination of a larger process of the reception of Islamic art that began centuries earlier. During my fellowship at the Center, I focused upon adaptations of Arabic calligraphy in the context of Italian Renaissance panel painting, especially in works found in the collection of the National Gallery of Art, such as Giotto’s Madonna and Child. I also finished an article on moresques, a concept closely related to arabesques. Moresques were complex radial designs adapted from metalwork objects imported from North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula. For the article as well as for my book, I have been focusing on Leonardo da Vinci’s frescoes for the Sala delle Asse in Milan, created under the patronage of Ludovico Sforza, known as Il Moro (The Moor). The article will be published in a special journal issue of CrossCurrents that I am coediting on the subject of the tree of life.

University of Connecticut

Samuel H. Kress Senior Fellow, 2023–2024

Kathryn Blair Moore will return to her position as associate professor of art history at the University of Connecticut for fall 2024.