Gregory Sholette

Backstories of Art and Activism: The 1871 Federation of Artists and the 21st Century’s Working Artists and the Greater Economy

Activist art has grown in stature over the past decade, with its occasionally militant practice now featured in biennials and museums even as their employees unionize in a new variant of institutional critique. Political change groups such as Black Lives Matter are labeled art world “influencers,” and theorist Boris Groys claims that activist art is unique to the 21st century. My current research contrarily seeks a “backstory” for activist art. The search drew me to the 1871 Paris Commune and figures such as Louise Michel and Gustave Courbet. The National Gallery of Art owns examples of Courbet’s seaside paintings made before and after the civil war, including his 1866 canvas Calm Sea, which contrasts tellingly with the stormy skies of Boats on a Beach, Etretat, painted after the Commune’s bloody repression sometime after 1872. Consider this visual pairing an epigram for my report.

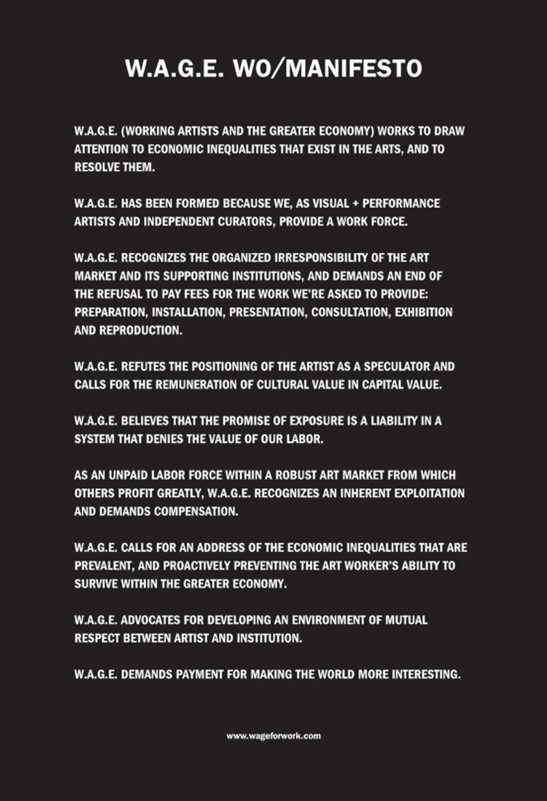

Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.), “W.A.G.E. Womanifesto, 2008. Poster produced in 2014 for the Wages 4 W.A.G.E. fundraising campaign.” Courtesy W.A.G.E.

Despite DC’s summer heat, the National Gallery’s interior was cool, and the Center’s outstanding resources allowed me to pore over various accounts of artists involved in the short-lived 1871 socialist experiment before it was crushed by the French army during the “Bloody Week” of May 21–28. My residency focused on the Federation of Artists (La Féderation des Artistes) and its proposal for restructuring the role of the decorative, industrial, and fine arts. But a more elusive inquiry involved disclosing whether or not their 19th-century reforms still resonate today in the very different 21st-century art world. After all, artists and artisans have repeatedly sought various degrees of collective self-regulation with examples ranging from medieval Europe to Renaissance Italy as well as Senegal, Benin, feudal Japan, and the Aztec Empire. Nonetheless, it surprised me how many of the Federation’s objectives resemble those in our current context.

The Commune’s Federation of Artists, which included more than 400 members, instituted policies of self-governance; established equality for all members regardless of gender; called for freedom of expression; and made innovations in forms of patronage, curating, and art education. A definite sonority appears to link these 19th-century reforms with the aims and ideals of artists in recent decades, including the missions of such self-organized collectives as Occupy Museums and Working Artists and the Greater Economy, or W.A.G.E. Both groups emerged after the 2008–2009 economic meltdown, advocating for improved financial and social resources for artists. With regard to W.A.G.E. in particular, the all-woman group has since developed a set of management tools for not-for-profit cultural institutions aimed at assuring artists are paid appropriate fees when the funding sources are public. As of 2023, over 100 small to midsize US arts organizations are voluntarily W.A.G.E.-certified, including the Washington Project for the Arts. The momentum of this growing covenant is also generating peer-to-peer pressure for those arts organizations not yet certified to do so.

Gustave Courbet, Boats on a Beach, Etretat, c. 1872/1875, oil on canvas, Gift of the W. Averell Harriman Foundation in memory of Marie N. Harriman, 1972.9.7

Certainly, the desire for artistic autonomy manifests differently now than in late 19th-century northern Europe, wherein artists sought a degree of sovereignty from aristocratic interests, the church, and a fast-rising bourgeoisie. While present-day art practices still depend on state and municipal benevolence, influence today is more typically brought to bear via private, market-driven forces. And yet, the existential precariousness of the majority of artists remains much the same as it was in the past. Despite being highly educated—in fact frequently overeducated when compared with other professionals—contemporary artists in the United States hold an average of two to three non-art-related jobs in order to support their practices. As W.A.G.E. asserted in 2008, “we demand payment for making the world more interesting.” Likewise, the 1871 Federation of Artists called for entrusting “the keeping and the administrative supervision of the committee…in order to encourage studies and satisfy the curiosity of visitors.”

No one would disagree that in theory these demands might make the world more interesting. Still, the Federation’s goals were far more politically sweeping than the more laissez-faire motto of W.A.G.E. (and I note group cofounder Lise Soskolne feels this early slogan no longer represents “the complexity of the demand anymore,” indicating an important transformation). The Commune’s Artists’ Committee, of which Courbet was a founding member, also pledged to apply their artistic labor toward the “inauguration of communal wealth, the splendors of the future and the Universal Republic.” Is there an equivalent vision for the artist’s role in society today? How might contemporary artists be haunted by backstories that are known, unknown, or even repressed? This is the investigative direction that my post-Center research now takes.

Queens College, City University of New York

Paul Mellon Visiting Senior Fellow, June–August 2023

Professor Gregory Sholette is incorporating research undertaken at the Center into a book to be published by MIT Press. He was recently honored to become affiliated faculty of the CUNY Graduate Center Earth and Environmental Sciences program and continues to serve as codirector of Social Practice CUNY, a Mellon Foundation–funded art and social justice project.