George Baker

Paul Thek and the Italian South: From Pop to the Popular, from Process to Procession

In the 1960s, American artist Paul Thek (1933–1988) collaborated with and exhibited alongside Andy Warhol (1928–1987). Like the pop painter, Thek was then considered one of the most important artists to emerge in his generation. Thek’s initial works, sometimes called his “meat pieces” (or later, “Technological Reliquaries”), were suspended ambivalently between pop art and minimalism, between figuration and abstraction, between painting and sculpture.

Paul Thek, Invitation card for A Procession in Honor of Aesthetic Progress: Objects to Theoretically Wear, Carry, Pull or Wave at Galerie M. E. Thelen in Essen, 1968. © Estate of Paul Thek

Immediately celebrated for this work, Thek befriended Susan Sontag (1933–2004), inspiring the title of her key essay collection, Against Interpretation (1966; she would also dedicate her 1989 text AIDS and Its Metaphors to Thek); engaged in a close dialogue with the minimalist sculptor Eva Hesse (1936–1970); and fell in love with the photographer Peter Hujar (1934–1987). Thek occupied an eccentric but paradoxically central place in the New York avant-garde.

By the 1970s, however, Thek’s reputation had all but been eclipsed. Part of this shift in critical reception resulted from the artist’s increasing expatriation from the United States to Europe. Traveling to Italy and then establishing a series of studios there, Thek’s work was deeply transformed by popular and folk culture of the Italian South. The collision of cultures propelled a unique position and set of strategies in Thek’s work that raise relatively unprecedented methodological and theoretical questions in this historical moment and context. Without being fully understood or acknowledged, Thek’s work nonetheless deeply shaped the future development of art, increasingly so in our present. My current research hopes to open up the full range of popular cultural practices addressed during Thek’s “Italian turn,” seeking to return to our accounts of contemporary art this lost political and cultural horizon.

In 2010 I initiated research on Thek, collaborating on Paul Thek: Diver, A Retrospective. My essay, “Notes on the Underground,” addressed the “minor” mode of Thek’s painting after 1970, his small-scale and often whimsical works on newspaper grounds. But this idea of a “minor” painting, in the sense given the term by Gilles Deleuze, can be connected to the “minor” art forms that everywhere erupt in the Italian South, reaching back toward antiquity and embracing the long history of popular religious culture—ex-voto shrines, crèche scenes and religious dioramas, ossuaries and papier-mâché figurines, reliquaries and ceramics, and the trappings of religious processions and festivals.

It has long been accepted that Thek’s canonical early work, his Technological Reliquaries, were articulated in relation to his first sojourns in Italy. In 1962 and 1963, Thek traveled to Italy, establishing a friendship with Cy Twombly (1928–2011) and links to the gallerist Topazia Alliata (1913–2015). Thek would have his first show in Rome after spending the summer of 1963 in Sicily with Hujar, who had received a Fulbright to study abroad. Hujar’s photographs (and portraits of Thek) in the Capuchin catacombs in Palermo would come to public notice a decade later, in his notorious photobook Portraits in Life and Death (1976), where the Sicilian images were paired with a pantheon of portraits of the downtown New York cultural underground. Thek’s bodily fragments in his Technological Reliquaries made a more immediate connection—and incongruous crossing—between avant-garde practice and this specific Sicilian monument and cultural/religious practice. By 1968 Thek would himself receive a Fulbright, moving more permanently to Italy, with a studio in Trastevere in Rome and taking up periodic residence on the island of Ponza.

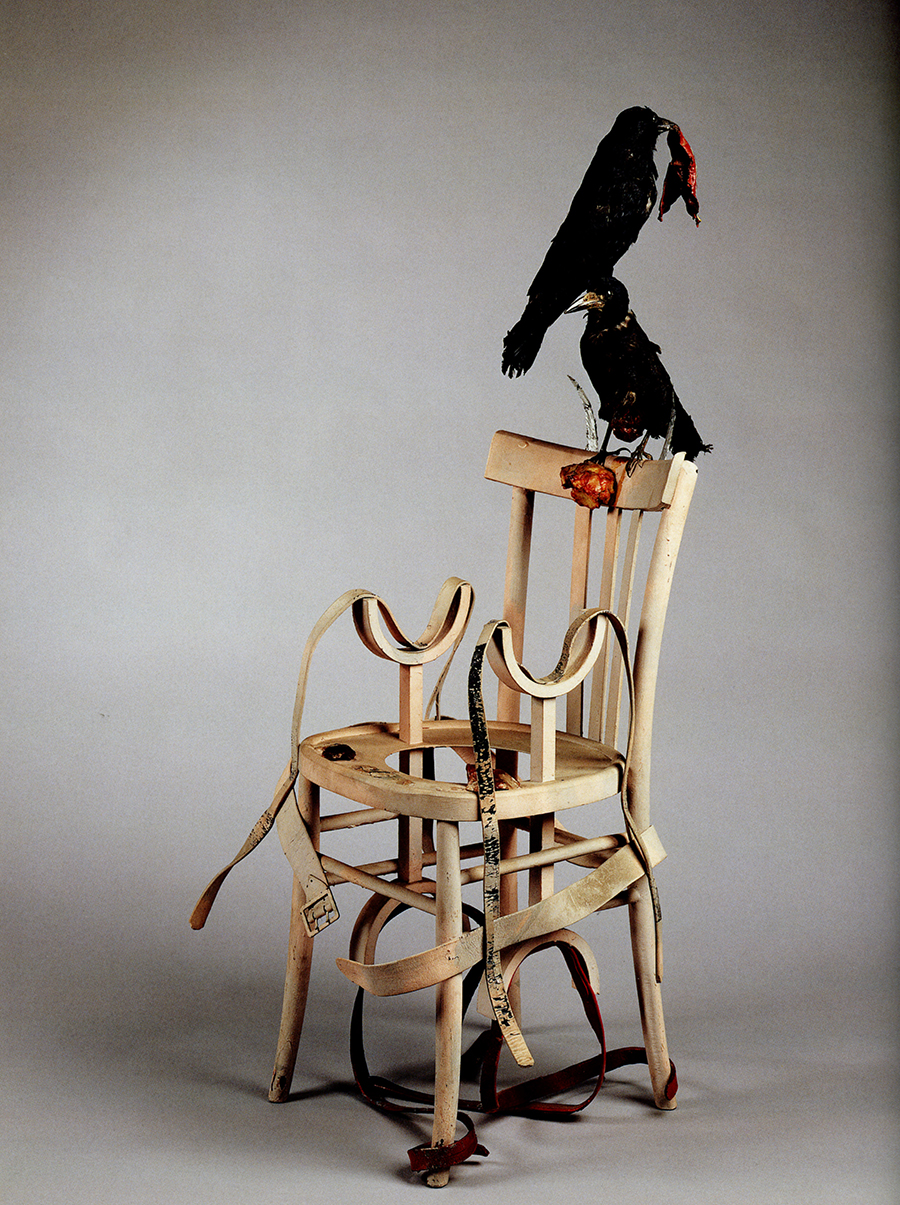

Paul Thek, Untitled (Chair with Crows and Meat), 1968, chair, leather straps, paint, taxidermic animals, and wax, Kolumba Museum, Cologne. © Estate of Paul Thek

This is the moment when Thek’s work becomes increasingly transformed; the moment contemporary art history begins to lose the ability to parse and understand the work more generally; and the moment in which Thek’s engagement with popular Italian culture explodes. From Rome, in 1968, Thek prepared an exhibition entitled A Procession in Honor of Aesthetic Progress: Objects to Theoretically Wear, Carry, Pull or Wave. Moving from “pop” art to the popular, from minimalist “process” art to the trappings of a cultural procession, Thek’s “sculptures” were all deeply related to the kinds of props and religious costumes worn or carried in patron saint festivals. My research has traced the religious festivals we know Thek experienced in the Italian South—an Easter trip to Stromboli in 1963; a key summer festival for Saint Joseph in the village of Casteldaccia, near Palermo, where Thek lived; and later processions central to Ponza. After 1968 Thek focused on large-scale installations almost always called processions, made collectively with a team of collaborators (The Artist’s Co-op). Individual sculptural elements involved body casts covered in rubber fish (Fishman), or decorative dwarfs and kitsch animals made for Thek by an Italian craftsman named “Contrucci.” Myths or folktales eventually erupt everywhere in the work, from Italy and beyond—the Pied Piper, Tower of Babel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Mr. Bojangles.

Part of this project will allow new connections to be drawn between Thek and contemporary artists on whom I have also been working. But the majority of the remaining work will be in opening up dialogues around the “popular” emerging from Thek’s connection to Italy in the 1960s and ’70s, looking to case studies and comparisons with Alberto Burri (1915–1995), especially his large-scale public work in Sicily; specific ties with Arte Povera figures who were from the Italian South or the Mediterranean, such as Pino Pascali (1935–1968) and Jannis Kounellis (1936–2017); and the work and writings of Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922–1975).

In this, the project hopes to raise anew what Antonio Gramsci called the Southern Question, but now in relation to the dynamics of contemporary art, a re-centering of questions of class and labor in a moment in art history that has largely voided such concerns. Pasolini’s idea of cultural “contamination” also provides a matrix for rethinking the hybrid challenges of Thek’s work, and this idea emerges in relation to the same cultural dynamics Thek was navigating. The specific encounter Thek proposed with the Italian South, and the modes of “minority” his work entered through this embrace, have been almost entirely repressed. But they elaborate new critical models for artistic practice that seem increasingly relevant to our current cultural conjuncture. The task is not to reclaim such sources as “iconography,” in the usual manner of high art’s colonization of the popular. Thek instead proposed something more like an inversion of such dynamics, transgressing the dominant languages of pop, minimalism, and other contemporary art forms through their dual articulation with “dominated” cultural forms.

University of California, Los Angeles

Paul Mellon Visiting Senior Fellow, March–May 2024

George Baker recently published a book encompassing two decades of reflection on contemporary art and photography, entitled Lateness and Longing: On the Afterlife of Photography (2023). His next book will be an edited anthology of critical essays on the artist Tacita Dean. In the wake of his residency at the Center, Baker will return to UCLA, where he will become chair of the Department of Art History beginning in summer 2024.