Erin Dickey

“Bad Information”: Networks, Knowledges, and Feminist Art in the 1980s

In an era of accelerating technological change, the work of Judy Malloy (b. 1942), Nancy Paterson (1957–2018), and Karen O’Rourke (b. 1951) probed the political and aesthetic processes underlying the “information age,” scrutinizing not just what but how we know. My dissertation, completed during my year in residence, explores the convergence of networked technologies and feminist art in the 1980s, analyzing the material histories of select early career works from these artists. In this decade, the proliferation of personal computing coincided with deregulation in financial and telecommunications sectors, Cold War anxieties, and a shifting landscape of political possibilities for art. Linked by shared feminist politics and collaborations with intersecting digital arts communities, these artists used databases, the internet, fax machines, live video transmission, and other tools to destabilize common associations of technology with spectacle and efficiency. Grappling with both the possibilities of networked communication as well as dynamic expressions and neutralizations of oppositional politics under neoliberalism, the art at the center of my study signals and negotiates the fraught relationships among technology, feminism, and knowledge production at the end of the 20th century.

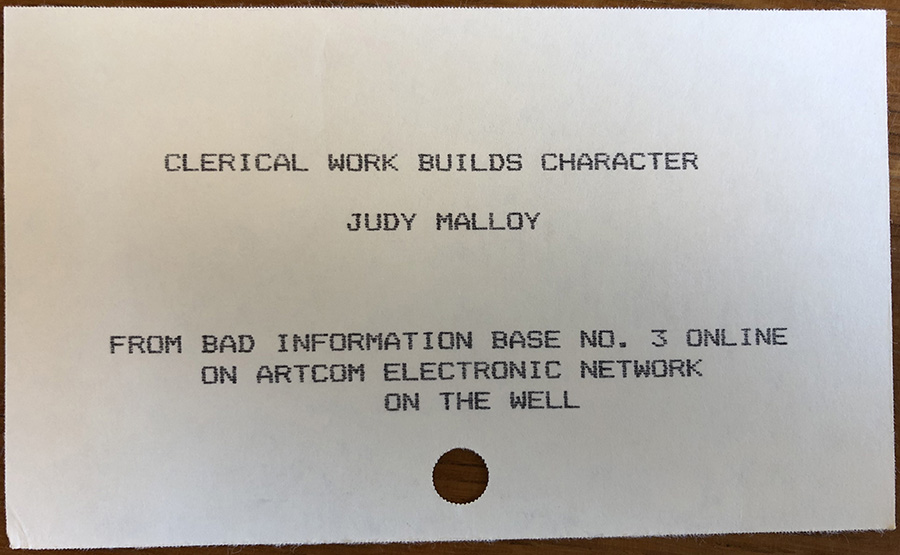

Judy Malloy, Catalog card from Bad Information Base No. 3, c. 1986, Stanford University Libraries, Special Collections Department, Art Com records, c. 1970–2005, box 253. Photo: Erin Dickey

Explored in Chapter One, Malloy’s information art interrogated the invisible authority of networked information search and retrieval. Based in the Bay Area, she structured a set of interrelated projects around her performed “founding” of three fake Silicon Valley technology corporations, OK Research (1980–1982), OK Genetic Engineering (1983–1985), and Bad Information (1986–1995), assuming the persona of a technology company executive to collect scientific and promotional materials. Malloy then reconfigured selections from this information into artists’ books, mail art, databases, installations, and interactive online art. At the core of these engagements was a profound ambivalence about the ascendent ethos of market-based knowledge production, driven by the metastasizing information technology industry to which she was adjacent.

Chapters Two and Three read the work of Canadian artist Nancy Paterson in tandem with changes in both the conditions of networked communication and feminist discourse about the construction of collective political agency and the individual subject under globalization. Chapter Two analyzes a collaborative contribution by Paterson, Peggy Smith, and Derek Dowden (Signal Breakdown—Semaphore Piece) to Robert Adrian’s The World in 24 Hours, a large-scale telecommunication art event at the 1982 Ars Electronica festival. Through mediated performance connecting an embodied basis for knowledge with the material history of telecommunications, Signal Breakdown—Semaphore Piece complicates technophilic ambitions toward a frictionless but hyper-connected global order.

Judy Malloy, Bad Information logo, 1986. Image courtesy of the artist

Chapter Three casts Paterson’s later networked installation, Stock Market Skirt (1992–1998), as a counterpart to Signal Breakdown—Semaphore Piece, each work situating a feminized bodily form as a site and medium of information transmission. Stock Market Skirt connects a motorized party dress on a dressmaker’s dummy to stock data accessed in real time from financial websites. In contrast to Signal Breakdown—Semaphore Piece, Stock Market Skirt presents a flexible, feminized subject as an effect of subjectivizing technological strategies. Paterson’s 1980s–1990s media art installations and later turn to information policy studies reflect a deep concern over the commercialization of the internet and the coalescence of monopolies within the tech industry. As her work tracks dismay over the subsumption of socially dominant strains of feminism by neoliberal capitalism, it nevertheless explores a spectrum of understandings of the political valences of the interface, from a mechanism of control to a vehicle for liberation. For Paterson, an early, under-acknowledged theorist of cyberfeminism, feminist politics and information politics were linked.

Chapter Four analyzes City Portraits (1989–1991), a series of fax art events premised on the exchange and collective manipulation and construction of images of cities. Conceptualized and coordinated by O’Rourke, City Portraits was carried out by an international network of artists, Art Réseaux. The project aimed to search out “the possibilities of exchanging images by telephone” by staging communication events between groups of artists in their respective cities. Both City Portraits and a later, related work on CD-ROM, Paris Réseau/Paris Network (2000), play with increasingly complex ways of inhabiting and knowing space and place, advancing an implicitly feminist geography.

These works are particularly relevant to our current moment. Awareness of capitalism’s tendency to devour its critiques and a sense of the limitations of the second-wave feminist project undergird them. Viewed from the vantage point of the 2020s, they portend an era of widespread distribution of mis- and disinformation across computer networks, while also verifying the unpredictability of networks. Revealing how networked technologies build and unbuild epistemic conventions, especially as they relate to the existence, experiences, and perceptions of particular bodies in space, works by Malloy, Paterson, and O’Rourke attest to the possibility, necessity, and affective experience of collating multiple realities.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Twenty-Four-Month Chester Dale Fellow, 2022–2024

Erin Dickey completed and defended her dissertation in spring 2024. Following her fellowship, she will continue to pursue her research in North Carolina.