Courtney R. Baker

Cinematic Slavery and Its Fine Arts Precedents

My research at the Center focused upon the enduring visual cultures of slavery and abolition as represented in early 21st-century cinema and rooted in earlier, pre-photographic visual media. My primary focus involved developing a chapter of my book manuscript on the visual cultures of Twelve Years a Slave, an 1853 memoir by Solomon Northup (1807/1808–1867). In this chapter, I discuss the printed book’s use of image and narrative together as foregrounding the 2013 cinematic adaptation’s visual vocabulary, which repeats some of the innovative representational gestures of the book. In doing so, we are able to see the collusion of narrative and image in the construction of the Black representational subject. Such an attention loosens its grip upon historical accuracy as the proper valuation of Black representation.

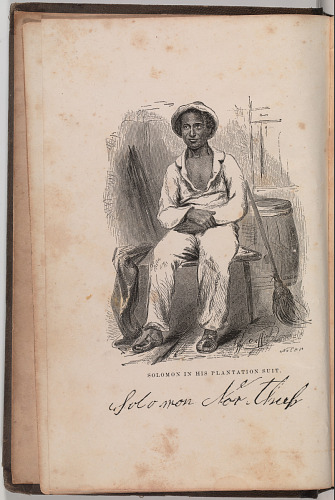

Nathaniel Orr, Solomon in His Plantation Suit, 1854, engraved plate in bound volume, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

The project entails a formalist interpretation of the original book and engravings as well as of the 2013 film adaptation directed by artist and filmmaker Steve McQueen (b. 1969). In order to contextualize the representation of African Americans as an effect of labor rather than as an unmediated, authentic image, I focused upon depictions of African Americans at work, including the conventions of genre painting and book illustration that prevailed at the time of Northup’s writing. In presenting expressions of Black aesthetic labor, I argue, the two works—Northup’s memoir and McQueen’s film adaptation—locate the aesthetics of violence, enslavement, and freedom within the respective regimes of literary and cinematic representation. Both works recruit and navigate Black representational labor as a process of escaping capture.

By addressing the visual representation of African Americans in the late period of American slavery, I reconsidered the provocation by theorist Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) to reevaluate art in the age of mass-produced images. Benjamin’s thesis has been a crucial text for film studies, which identifies the cinematic medium as a form of image-centered mechanical reproduction; however, the text is also seminal for its discussion of art’s value, production, and circulation within financial and cultural markets. By centering the conscripted labor of African Americans as the subject of the image and the means of image-making, I displace Benjamin’s concerns from the early 20th century and apply them to the 19th. A close analysis of Northup’s text and its accompanying illustrations by Frederick M. Coffin (1822–?), engraved by Nathaniel Orr (1822–1908), complicates Benjamin’s time line and so places Blackness at the center of two of modernity’s core concerns: representation and industrialization.

Richard Norris Brooke, A Pastoral Visit, 1881, oil on canvas, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund), 2014.136.119

Reading McQueen’s film formally reveals an attention to the spectatorial gaze and a reflection of the painterly compositions that characterize 19th-century American genre and abolitionist painting. The film exhibits a sensitive play with the visual availability of the Black body, recalibrating the pleasant pastoral effect of a work such as Negro Life at the South (1859) by Eastman Johnson (1824–1906) to highlight the banal cruelties of the plantation. Likewise, the film’s conclusion rejects the availability of the Black family’s intimate moment, such as that portrayed (albeit sensitively) in A Pastoral Visit (1881) by Richard Norris Brooke (1847–1920). Instead, McQueen depicts the reunited family encircled in an embrace that the camera and, consequently, the viewer cannot penetrate.

The second project entailed another chapter of the book discussing the 2013 film Belle, directed by Amma Assante (b. 1969), and its source text: a double portrait of Black British gentlewoman Dido Elizabeth Belle (1761–1804) and her cousin, Lady Elizabeth Murray (1760–1825), by Scottish painter David Martin (1737–1798). This chapter explores the paintings, sculptures, and other features of the film’s mise-en-scène, such as textiles, in the context of the 18th-century British slave trade—which is obliquely critiqued in the film through its main character, Belle. I consider the inclusion of a neoclassical Venus Pudica in a story about (among other things) an engagement thwarted by racism. The conventional pose of the sculpture reflects broader and enduring symbolisms of enslaved women’s sexuality, a theme that was engaged later by the American sculptor Hiram Powers (1805–1873) in his provocative Greek Slave (1843). The film positions the completion of Martin’s double portrait as an achievement of justice and equity; it is further aligned with a parallel courtroom narrative regarding the case of the slave ship Zong, which is considered to have led to Britain’s abolition of transatlantic slavery. However, in attending to the inherent critiques of visual evidence embedded within Belle, the film exposes rather than closes fissures and inconsistencies regarding the achievement of justice and of social equity. Both films, therefore, return us to the legacies of looking at Blackness and the labors—physical, industrial, and ideological—of their production and circulation.

University of California, Riverside

Beinecke Visiting Senior Fellow, November–December 2023

Courtney R. Baker will return to her position as an associate professor of English at the University of California, Riverside. In spring of 2024, she will hold a Mellon Humanities Quarterly Fellowship at her home institution to work on additional chapters of her manuscript.