Brian D. Goldstein

If Architecture Were for People: The Life and Work of J. Max Bond Jr.

Architecture has recently entered a period of soul-searching, as academic departments, professional organizations, and firms have all asked how they can better engage in the struggle for racial justice. Yet while such questions have gained new urgency, they are not, in fact, new. The few Black professionals who made it to the drafting table in a dominantly white field had been asking such questions all along. That was particularly the case for J. Max Bond Jr. (1935–2009), the most prominent African American architect in the late 20th century. Born into a family of activists and a designer focused on the question of how modern architecture could be a tool for liberation, Bond demanded racial reckoning throughout his professional life. If often overlooked during his career and since, his pursuit has only gained more importance over time.

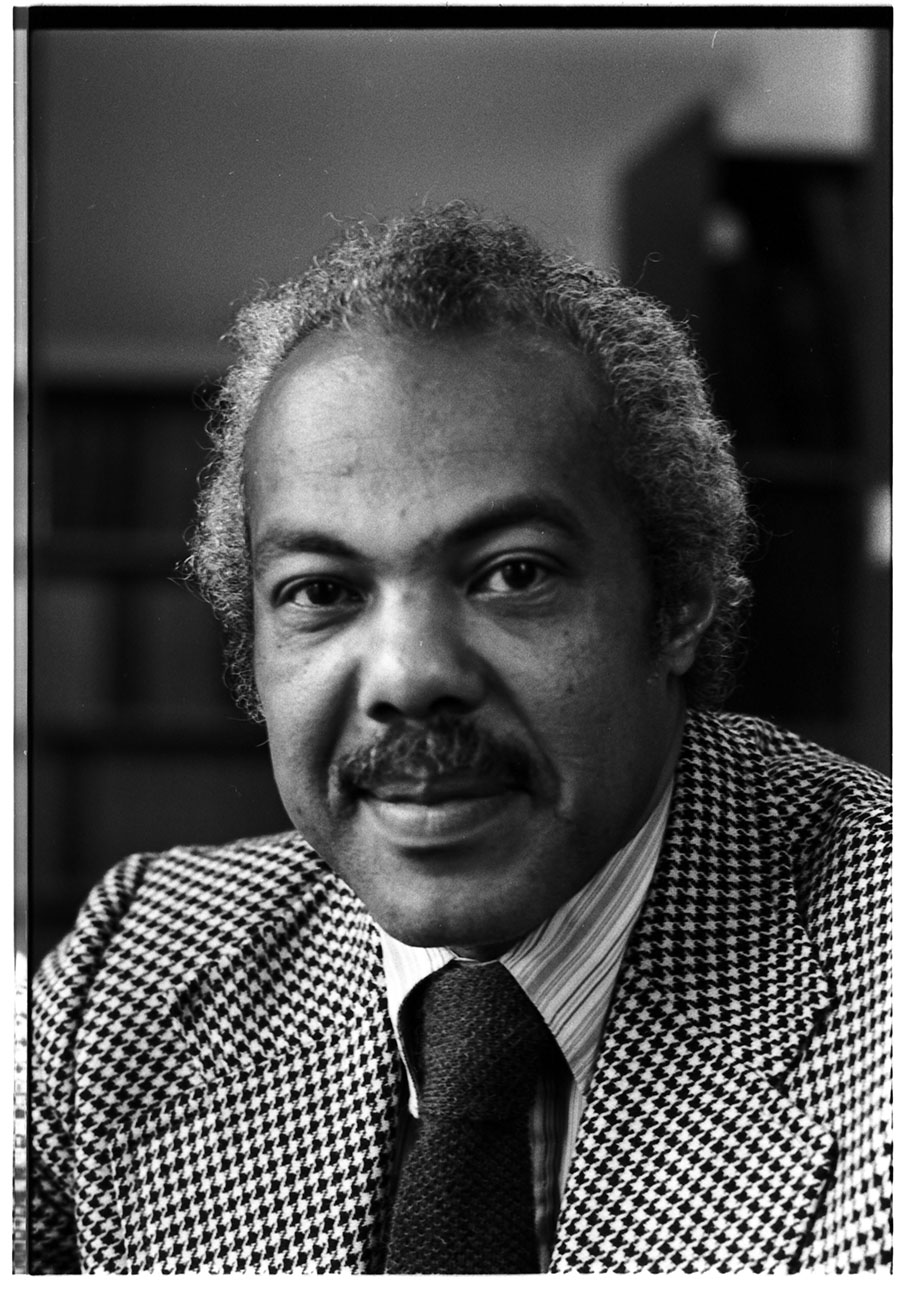

J. Max Bond Jr., 1980. Photo courtesy of Davis Brody Bond

The book manuscript I have been writing during my fellowship, If Architecture Were for People: The Life and Work of J. Max Bond, Jr., answers an essential question that preoccupied Bond throughout his career—how can architecture help shape a more just world?—while revealing the still-profound limitations upon such hopes. In addressing that question through the biography of a compelling individual, this project traces several broader threads: the history of Black architects in the postwar United States, the history of modern architecture through the lens of race, and the history of the civil rights movement from the perspective of the built environment.

Bond grew up throughout the Deep South; lived at times in Haiti, France, Tunisia, and Ghana; and learned architecture in its most vaunted spaces, including Harvard University. He went on to a career of firsts and mosts. Bond Ryder Associates, which he cofounded, gained a reputation as the leading Black-led firm in the post-1968 period. At City College of New York, he became the first Black dean of an architecture school not at a historically Black college or university. And at Davis, Brody & Associates, he became the first Black partner of a majority-white New York firm. Along the way, Bond designed housing, public buildings, and monuments to the history of the long struggle for racial justice, including the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, and—as part of a team—the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

In tracing these sites, If Architecture Were for People provides a new perspective on two sweeping movements that transformed the postwar world: modernism and the civil rights struggle. Modernism had often functioned as a tool of domination, despite its claims to build a better world. Instead of abandoning modernism, however, Bond held it to its utopian promises, shaping an internationalist approach that rejected the field’s Eurocentric, elite biases; celebrated urban spaces and the people—especially Black people—who lived in them; and sought broad participation from first conception through eventual use. In writing the book’s latter chapters during this year, I have focused on projects like Atlanta’s King Center, completed in 1982, where Bond prioritized materials, like brick, that would employ Black workers—a practical response to ongoing histories of racial discrimination that also foregrounded radical goals of economic justice. In these ways, I argue, Bond shaped a practice of socially engaged architecture that offered an alternative path in a field ever more focused on spectacular buildings and captivating images.

Bond Ryder Associates, Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, Atlanta, Georgia, 1982. Photo courtesy of Davis Brody Bond

At the same time, Bond faced persistent obstacles, even despite his success, that revealed the precarious reality for designers of color. Social barriers that limited potential clients, economic insecurity, exclusion from professional media, and veiled snubs offered in the language of design critiques were all common experiences for Bond and his peers. As a result, the architecture profession marginalized the alternative approach Bond modeled, just as a range of social, cultural, and political forces sidelined the aims of the civil rights movement in the same decades. From Bond’s point of view, one finds both a more promising and more pernicious history than is typically told of 20th-century architecture.

Putting Bond at the center of the story has allowed me to approach familiar and often storied places from a new angle. In these places, Bond asked questions that have not stopped reverberating: How do we build sites that reflect their diverse users? How should we remember difficult histories so that people may learn from them? How can buildings and plans not just shape space but move toward constructing a better world? Bond recognized that a single profession could not answer such questions, but likewise understood that his had often caused much harm. In shaping a civil rights modernism, he offered a path whose attention to participation and labor, past history and future use, suggests a way forward.

Swarthmore College

Paul Mellon Senior Fellow, 2023–2024

In fall 2024, Brian D. Goldstein will return to Swarthmore College, where he is associate professor of architectural history in the Department of Art and Art History. Through the end of the year, he will continue to write If Architecture Were for People with support from a National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholars grant.