Alla Vronskaya

Environmental Colonization: Architecture, Climate, and Geography in the Cold War Soviet Union

My residency at the Center enabled me to commence work on a book manuscript that examines how, during the 20th century, Soviet architects and theorists systematized, classified, ordered, and regulated the geographic and climatic diversity of the Soviet Union and other regions, particularly in the Global South, where they increasingly found themselves working. While the study, production, and organization of space sustained governmentality and control, these practices also allowed for the participation of local actors. My project thus highlights architectural theory’s role as a mediator between the universal and the specific—the center and the periphery—and details the spatial and organizational techniques of this mediation.

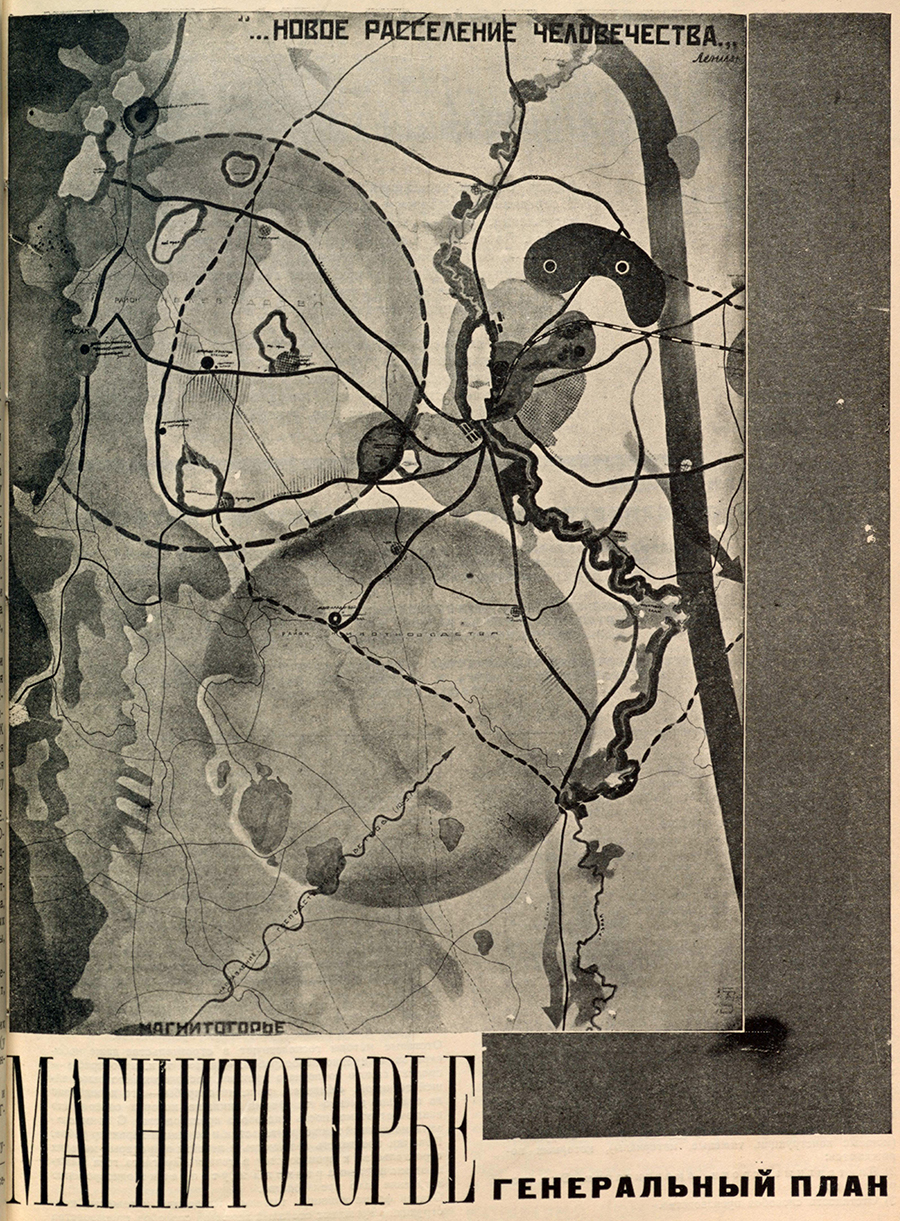

Mikhail Barshch, Vyacheslav Vladimirov, Mikhail Okhitovich, and Nikolay Sokolov, with Georgy Vegman, Nina Vorotyntseva, Alexander Pasternak et al., Magnitogorye (competition project), 1930, from Mikhail Barshch, Vyacheslav Vladimirov, Mikhail Okhitovich, and Nikolay Sokolov, “Magnitogorye,” Sovremennaya arkhitektura, no. 1–2, 1930

Beginning with the 1920 Plan of the Electrification of Russia, which aimed at creating a national network of energy production facilities that would enable subsequent industrialization, the Soviet economy relied on interrelated principles of central economic planning and territorial expansion. Together, they laid the foundation for the Soviet project of colonization (kolonizatsiia), which state ideology juxtaposed with exploitative colonialism (kolonizatorstvo). As a term, “colonization” was soon replaced with “exploration” and “development,” and indeed, early Soviet colonization, which was closely related to both overseas colonialism and internal colonization projects, would during the Cold War seamlessly transition to programs of economic development, implemented both internally and abroad.

Initially driven by land scarcity in the European part of the Russian Empire and the intensifying extraction in Siberia, colonization was supported by the creation of a network of settlement. The multivalent term “settlement” addressed the process of migration, the unit of urban planning, and techniques of rooting residents in their new homes to prevent further migration. Creating the network of settlement became the task of the new academic field of constructive geography as well as its subfields—population geography, agricultural geography, urban geography, transportation geography, and distribution geography, among others—all of which aimed at designing, rather than describing, geographic regions and their economic roles. Architecture was called to support this project by spatializing solutions.

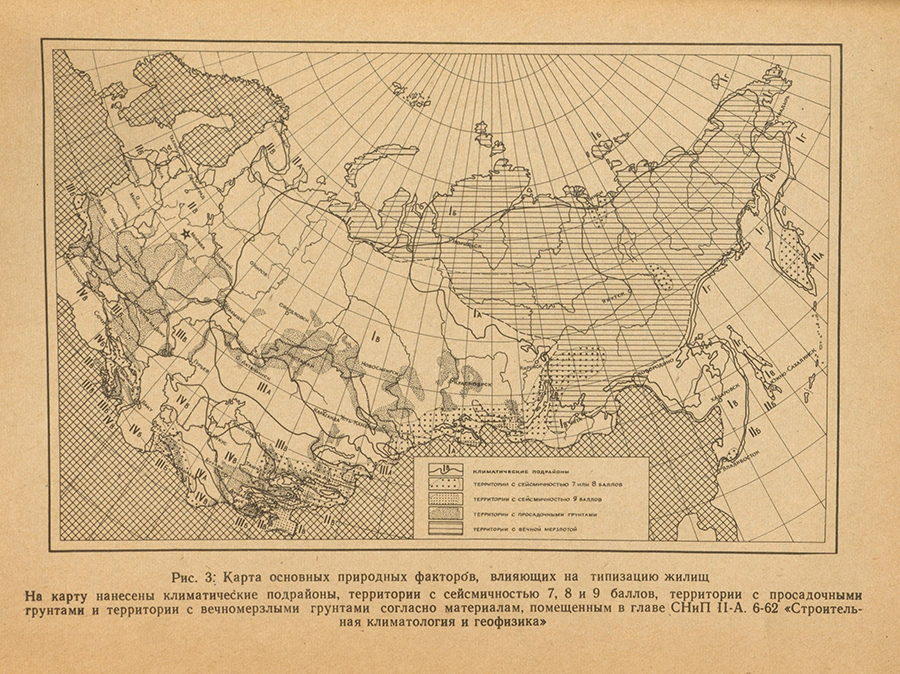

Map of main natural conditions affecting the typification of housing, from Stroitel’no-klimaticheskoe zonirovanie territorii SSSR [Climatic zoning of the territory of the USSR for construction] (Moscow, 1967)

Mass-scale settlement was enabled by the serialized industrial production of prefabricated elements, a national priority since Nikita Khrushchev’s return to modernism in 1954. To adapt the principles of serialization for regional and local differences, architectural theory relied on a set of interrelated organizational strategies: regionalization, typification, norming, and zoning. If at first Soviet construction norms were developed by regional authorities, in 1930 the country was divided into four climatic zones, each receiving specific recommendations for design and construction. In the course of the subsequent decades, these zones were subdivided into subzones, whose number eventually rose to 16. The Central Institute of Experimental Design, with “zonal” branches in Leningrad, Kyiv, Tbilisi, Novosibirsk, and Tashkent, was tasked with developing experimental projects for specific natural conditions. Moreover, zoning (including for climate, seismic activity, permafrost, and many other factors) lay at the core of the Soviet normalization system for architecture, Construction Norms and Rules, first published in the 1950s and continuously updated.

Working at an intersection of design, geography, demography, and economics, architects and regional planners determined the locations of factories, relationships between production and settlement zones, and between industrial and agricultural centers. Regionalization supported linking geographic units of various hierarchical orders—settlement, micro-region, region, macro-region, and, finally, the nation and the world—to ensure their coordinated work. On the urban mesoscale, these ideas informed the development of the concept of the micro-region as the base unit of Socialist Bloc urbanism. Furthermore, during the Cold War, the interwar concept of the region crystallized into the notion of the territorial-production complex, which synthesized economic and urban planning, acquiring a new life with the introduction of cybernetic techniques in the 1960s.

My fellowship at the Center provided me with dedicated research time and allowed me to take advantage of the excellent collection of Soviet publications and maps at the Library of Congress. I surveyed available publications, identified key case studies and actors, and refined the argument and structure of my manuscript. I focused on its first chapter, devoted to the 1929–1930 debate between two groups of architects—“the urbanists” and “the disurbanists”—in the context of the transition from human to regional geography. Arguing for a continuity between interwar and Cold War urban planning, the chapter links disurbanism with the principle of the combine or “geographic conveyor belt” proposed by Nikolay Kolosovsky, who later developed it into the concept of the territorial-production complex. I am immensely thankful to the Center for providing me with the resources and opportunity to conduct this research, and to my colleagues in the academic community for the inspiring dialogue and discussion.

Universität Kassel

Ailsa Mellon Bruce Senior Fellow, 2023–2024

Alla Vronskaya will return to the Department of Architecture, Urban Planning, and Landscape Planning at the Universität Kassel, where she is professor of history and theory of architecture.