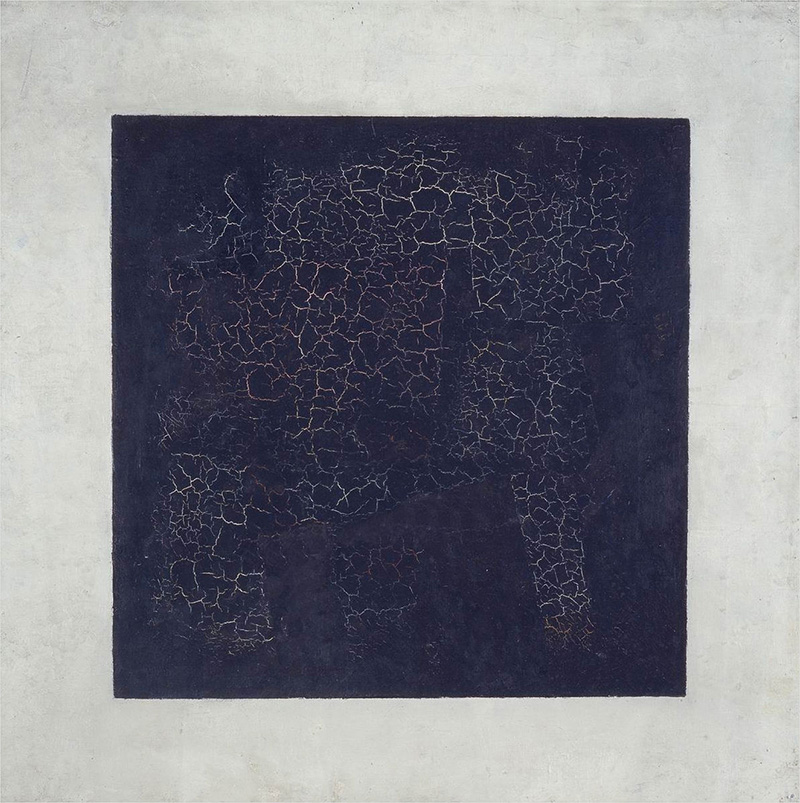

Each of these three projects is animated by a Black queer feminist approach to art-historical praxis that has enabled me, during my final year at the Center, to closely home in on the complex and often suppressed entanglement of Black being and modernist form. While scholars of African Diasporic art have long noted the rich interplay between Black cultural modalities and modernist artistic practices, such as assemblage, it is only recently that historians have begun to explore how putatively “Western” innovations like the monochrome, emblematized by Kazimir Malevich’s iconic Black Square of 1915, are deeply engaged with and in fact reliant upon facts and fictions of Black being. To wit, in 2015, conservators at Moscow’s State Tretyakov Gallery, equipped with X-ray technology, discovered that the Russian avant-gardist’s apparently blank ground obscures a translated snippet of a French racist joke—Alphonse Allais’s now infamous illustration of “Negroes Battling in a Cave at Night” (1898)—that was originally inscribed onto the canvas before it was embalmed beneath the painting’s top layer.

While Malevich’s painting features prominently in the introduction to Black Modernisms, in my subsequent work I have focused on another modernist icon, Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain of 1917, undoubtedly the artist’s most famous “readymade,” a mass-manufactured commodity that he transformed into a work of art by an act of elective ontological translation. In revisiting such tactics in an essay commissioned by the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt for their 2022 Duchamp retrospective, I aim to differently frame the significance of the artist’s interventions in the United States in relation to the work of Black radical thinkers, in particular that of Zakiyyah Iman Jackson.

Her remarkable 2020 book, Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World, helps us to freshly comprehend how Duchamp’s readymade object choices, while motivated to a certain extent, were foundationally enabled by an embrace of the very arbitrariness that has historically been viewed as that which consigns the “negro” to a near bestial state. For Western philosophers, none more so than G. W. F. Hegel, Africans’ seeming worship of randomly chosen natural objects was concrete evidence of their animality: Blacks had no cognizance of history, eternal law, or providence, which meant that they had no access to the concepts of ethics and morality that defined the European rational subject. Thus, with Fountain, I argue, Duchamp did not merely allegorize, but he performed a Western fantasy of the fetishistic blackened persona, highlighting white culture’s hypocrisies and reversals, while signifying on the antiblackness of its means of aesthetic appraisal.

This interpretation is furthered by the artist’s chosen pseudonym—initially intended to be used by his female friend who would submit the porcelain for exhibition—that Duchamp eventually affixed to the work as her/his “signature.” The letters, “R. Mutt,” scrawled on the urinal like a graffito, bring to mind a mixed-breed dog, so that the work flirts with those associations of animality, impurity, and sex/gender fluidity that also inform Western ideations of Black being. And, of course, Fountain was quite literally darkened in American photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s iconic picture of it, again reorienting the urinal, now as a feminized form that has called forth associations ranging from a silhouette of the Buddha to the human uterus flipped upside down. While artists like Pablo Picasso and Constantin Brancusi sutured preestablished “negro” and “feminine” forms together to evoke the specter of la négresse, Duchamp’s photographic coproduction of Fountain aims to one-up them in further dispersing such signifiers across the visual field, underlining the constitutive importance of Black female figures to avant-garde practice, whether they are incessantly recruited to appear or entirely volatilized out of sight.

University of Pennsylvania

Andrew W. Mellon Professor, 2020–2022

Huey Copeland looks forward to his first semester in residence at the University of Pennsylvania this fall and to beginning work on his next edited volume, OCTOBER File: Glenn Ligon, for the MIT Press.