Henri Matisse: The Fauves

The Wild Beasts

Paris, 1905. Henri Matisse, age thirty-six, has just arrived from the South of France with fifteen new paintings, including this one. Finally, he is pleased with his work. But when he submits the canvases to the Salon d'automne, the season's major public art event, the Salon president—fearing for Matisse's reputation—tries to dissuade him.

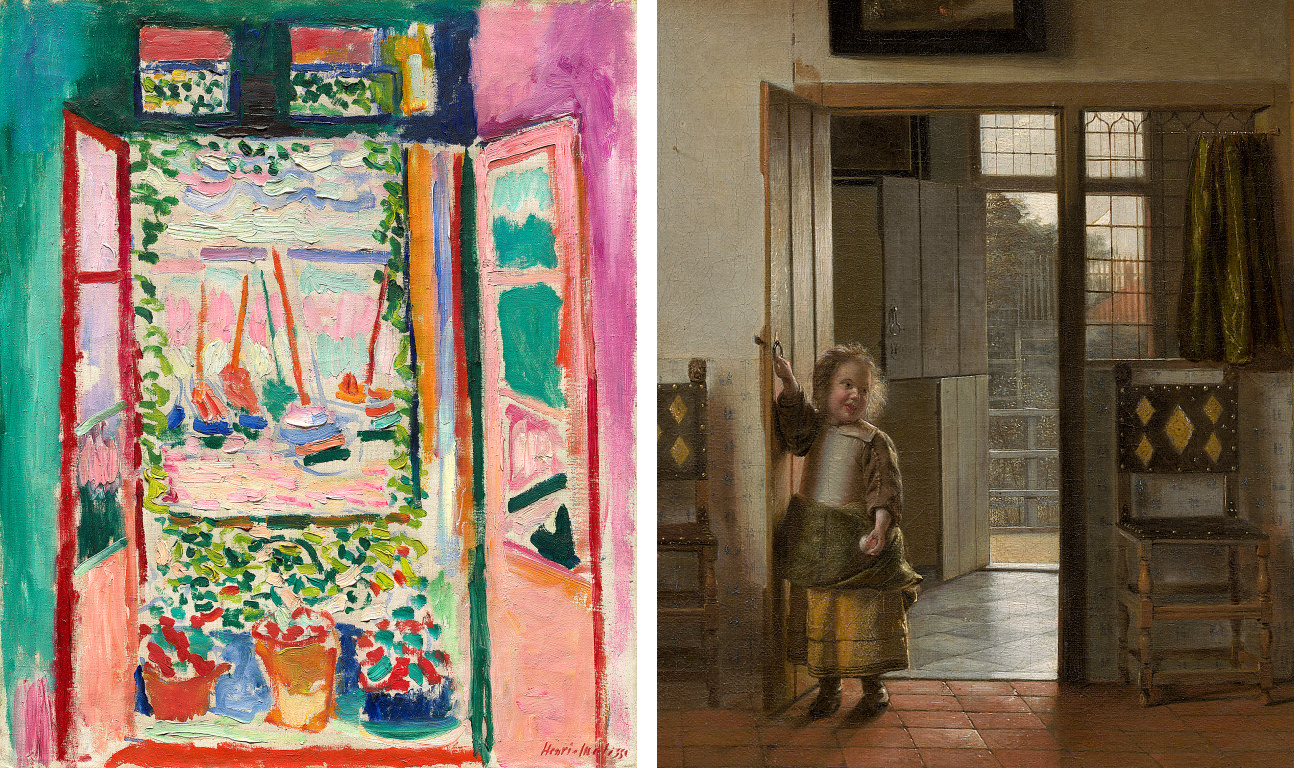

Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.7

Matisse and colleagues, including André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, and Albert Marquet, persevere, and their paintings are hung in Room 7. The public jeers at the "orgy of pure colors," judging the works primitive, brutal, and violent. The artists are dubbed "fauves"—wild beasts. Room 7 becomes "la cage."

The term fauve, actually coined by a generally sympathetic critic, has stuck. It describes a style that, while short-lived, was the first avant-garde wave of the twentieth century. The jeering audiences in Room 7 got an early look at what the century would bring.

Most of these fauve paintings were done in the years immediately after the 1905 exhibition.

(top left) André Derain, Charing Cross Bridge, London, 1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, John Hay Whitney Collection, 1982.76.3

(top middle) André Derain, Mountains at Collioure, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, John Hay Whitney Collection, 1982.76.4

(top right) André Derain, View of the Thames, 1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1985.64.12

(bottom left) Georges Braque, The Port of La Ciotat, 1907, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.6

(bottom middle) Albert Marquet, Posters at Trouville, 1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.1

(bottom right) Maurice de Vlaminck, Tugboat on the Seine, Chatou, 1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.4

The saturated colors of fauve paintings—all created between about 1904 and 1908—were not descriptive of nature. The paintings' bold strokes had an autonomous existence that often had little to do with mimicking surface appearances. The colors were unblended, without the subtle shading that suggests three-dimensionality. Their very brilliance and the strong rhythms of the brushstrokes worked against any perception of depth.

Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.7

These were paintings on the edge of abstraction. They negotiated new, unstable territory—were they essentially flat, patterned surfaces or a "window" onto the world? Fauve pictures stand at the border between pictorial illusion and the kind of "pure paint" that would become a preoccupation of twentieth-century modernism. As Matisse later observed, "Fauve painting is not everything, but it is the foundation of everything."

(top left) André Derain, Charing Cross Bridge, London, 1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, John Hay Whitney Collection, 1982.76.3

(top middle) André Derain, Mountains at Collioure, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, John Hay Whitney Collection, 1982.76.4

(top right) André Derain, View of the Thames, 1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1985.64.12

(bottom left) Georges Braque, The Port of La Ciotat, 1907, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.6

(bottom middle) Albert Marquet, Posters at Trouville, 1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.1

(bottom right) Maurice de Vlaminck, Tugboat on the Seine, Chatou, 1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.4

An Open Window

Open Window, Collioure is among the very first fauve works. It was painted during the summer of 1905, when Matisse, together with André Derain, worked in the small Mediterranean fishing port of Collioure, near the Spanish border.

When I put a green, it is not grass. When I put a blue, it is not the sky.

—Matisse

The view is full of light, inviting and vibrant. Through the window, small boats bob on pink waves under a sky banded with turquoise, pink, and periwinkle. This scene, reflected in the glass, melts into rectangles of smeary green, watery cyclamen, and lilac. The surrounding walls are fuchsia and blue-green—these are hardly the colors of nature.

Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.7

Instead of imitating nature, they have their own, almost abstract logic. Matisse was composing paintings, not just painting things. Color was how he conceived and structured his image. It does not simply convey what he saw—the boats, the vine growing around the balcony, the window panes—but is also decorative pattern in its own right.

Construction by colored surfaces. Search for intensity of color, subject matter being unimportant. Reaction against the diffusion of local tone in light. Light...expressed by a harmony of intensely colored surfaces.

—Matisse

Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.7

To maximize the intensity of his colors—and achieve the light he was looking for—Matisse organized his picture with pairs of complements. Orange masts rise from blue hulls. Potted plants on the balcony sprout red blossoms amid green foliage. Reflections oppose pink and turquoise, and in the walls these colors are reversed and deepened. Isolated by bare areas of canvas, these combinations generate a sort of visual vibration.

Because in composing Open Window Matisse largely used red, blue, and greens—in different forms—he enhanced the effect of light. These are the additive primaries—the wavelengths of orange-red, blue-violet, and green that combine to make white light.

Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.7

The composition is a nested set of opening "windows." Walls on each side frame the glass panes, which frame the balcony, which frames the harbor view. In each of these areas, Matisse has used different kinds of brushstrokes:

• long, blending vertical sweeps of the brush for the walls

• a flurry of short, squiggly marks in the balcony

• longer pulls, some vertical, some horizontal, for the sea and sky

Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure (details), 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.7

The very notion of an open window is an invitation to look into the distance. Yet, the differentiation of brushstrokes does not convince our eye that we are seeing a recession of planes. The different rhythms they set up create an overall decorative effect that compresses our perception of space. The vibrancy of the color also tends to trap our eyes on the surface, and the tonal gradations that would have more clearly defined near and far, inside and outside, are gone. Most of these are pure, unblended colors.

Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.7

"Out the window" is the illusion of volume and depth. A slight squint and we can almost see the image as an overall pattern of color, losing our hold on the "real" scene.

Matisse is moving painting in a new direction, toward greater autonomy from the thing depicted. It is surely no accident that he does so with a painting of a window. From the time of the Renaissance, the comparison of a painting to a window was a conceit pointing to the painter's ability to create an illusion of an outside reality. Now the painting asserts its own reality, as color and form.

(left) Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.7

(right) Pieter de Hooch, The Bedroom, 1658/1660, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Widener Collection, 1942.9.33

Influences

Fauve painters were influenced by several postimpressionist artists, especially Georges Seurat, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent van Gogh. These painters had turned away from the impressionists' aim of capturing primarily visual effects of light and atmosphere.

When Matisse arrived in Collioure in 1904, he had been working in the neoimpressionist style of Seurat, Paul Signac, and others. Hoping to give scientific rigor to impressionism, these artists had been experimenting with the use of pure, unmixed colors.

Seurat's Seascape illustrates their technique, called pointillism. Applying contemporary color theory in a rigorous way, the neoimpressionists juxtaposed tiny individual touches of pure color. They believed that these would blend in the eye to create a full range of colors more vibrant than could be achieved by blending pigments on the palette. Matisse, though, did not like the way the overall image became muted; the brilliance of the individual colors was lost when viewed at a distance. And he felt the neoimpressionist reliance on theory was limiting. "My choice of colors does not rest on any scientific theory; it is based on observation, on feeling, on the very nature of each experience."

Georges Seurat, Seascape at Port-en-Bessin, Normandy, 1888, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the W. Averell Harriman Foundation in memory of Marie N. Harriman, 1972.9.21

A retrospective of Paul Gauguin's painting had appeared at the 1903 Salon d'automne, and while Matisse and Derain were working in Collioure, they were also able to see some of Gauguin's last works in a town nearby. Gauguin used color expressively and symbolically to communicate interior states rather than surface appearances. Ordering and simplifying sensory data to its fundamentals, he urged other painters, "don't copy nature too literally." Massing colors into large, flat areas, Gauguin used their inherent emotive qualities to express intangibles.

Paul Gauguin, Parau na te Varua ino (Words of the Devil), 1892, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the W. Averell Harriman Foundation in memory of Marie N. Harriman, 1972.9.12

Before traveling to Collioure, Matisse had been chairman of a committee to mount a retrospective exhibition of works by Vincent van Gogh. The younger artist acknowledged that seeing Van Gogh's painting had "encouraged him to strive for a freer, more spontaneous technique, for more intense, more expressive harmonies." For Van Gogh color was powerfully expressive of emotion, and he laid it on the canvas in strong, purposeful marks.

Vincent van Gogh, The Olive Orchard, 1889, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Chester Dale Collection, 1963.10.152

This view of Collioure is one Derain made while working together with Matisse in the summer of 1905. Derain describes the trees and grass with long strokes of pure color—compare them to the strong, twisted lines Van Gogh used for his ancient olive trees. For both Derain and Matisse, however, color was a less emotional, less personal imperative than it had been for Van Gogh.

André Derain, Mountains at Collioure, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, John Hay Whitney Collection, 1982.76.4

Fauve Gallery

Matisse was deliberate and reserved, the opposite of wild. But Maurice de Vlaminck did match the public perception of what fauve painting represented: rebellion, roughness, disorder. A big, muscular man, Vlaminck raced bicycles, wrote racy novels, played the violin loudly, and embraced anarchy: "What I could have done in real life only by throwing a bomb...I tried to achieve in painting." He cultivated the fauve myth.

Vlaminck was a self-taught artist. Like Derain he lived in Chatou, a suburb of Paris, and the two often painted there together. Vlaminck's work exploded with bold new color and brushwork after he saw the paintings Matisse and Derain brought back from Collioure in 1905.

Maurice de Vlaminck, Tugboat on the Seine, Chatou, 1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.4

Compare Vlaminck's fauve painting of the river at Chatou with this impressionist view painted by Auguste Renoir some twenty years earlier. Both artists composed their images in a similar manner, but in other respects they differ. Renoir's gaily attired tourists, out for a leisurely day of boating, contrast with Vlaminck's working tug. Renoir's colors are bright complements, but his paint is applied with the subtle touches that make the scene appear scintillating. Like his subject matter, Vlaminck's brushstrokes—almost uniform—are more muscular.

Auguste Renoir, Oarsmen at Chatou, 1879, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Sam A. Lewisohn, 1951.5.2

While the public ridiculed the fauves, several critics were more appreciative, and some young artists found the new works thought-provoking and exciting.

One of those was Georges Braque, who had been pursuing a conservative, impressionist style. The Salon d'automne exhibition changed his art. Although Braque worked in the fauve style only briefly—about two years—he credited it as the step he needed to find his own way as an artist.

This view, like Derain's and Matisse's, was made in the warm light of the South of France. La Ciotat was a port and shipbuilding center near Marseilles.

Georges Braque, The Port of La Ciotat, 1907, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.6

The fauves benefited from the scandalous 1905 Salon d'automne. In a burgeoning market for modern art visibility was key, and everyone knew the "wild beasts." Dealers bought up fauve paintings. Derain was sent to London by his dealer Ambroise Vollard. Vollard particularly wanted Derain to paint some of the same subjects that had occupied impressionist Claude Monet only a few years earlier. Derain felt that several of his London paintings were his most successful fauve works.

(top left) André Derain, Charing Cross Bridge, London, 1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, John Hay Whitney Collection, 1982.76.3

(top right) André Derain, View of the Thames, 1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1985.64.12

(bottom) Claude Monet, Waterloo Bridge, Gray Day, 1903, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Chester Dale Collection, 1963.10.183

Marquet was a native of the northern French city of Le Havre, and his most important fauve works were those that he painted at coastal resorts in Normandy—like this view of Trouville. The colorful crowding of posters seems ready-made for the bold strokes and unmixed colors of fauve painting. Notice, however, how the sky and tawny sand are treated with more blended brushwork and nuanced coloring.

Albert Marquet, Posters at Trouville, 1906, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.1

From Fauve Forward

Fauve painting did not have the concerted and sustained momentum of a coherent movement. The fauve period lasted only a few years, from about 1904 to 1908. The artists, never formally associated, moved on to work in other styles. We take a brief look at the future of two of them, Braque and Matisse.

(left) Georges Braque, The Port of La Ciotat, 1907, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.6

(right) Henri Matisse, Open Window, Collioure, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.7

Braque

Braque, in fact, somewhat suppressed his fauve paintings, not considering them part of his mature body of work.

The Port is one of the more naturalistic paintings Braque made at La Ciotat. His work there became increasingly abstract—brushstrokes gained autonomy while the objects they depicted became more cryptic. Space became more ambiguous.

Georges Braque, The Port of La Ciotat, 1907, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney, 1998.74.6

Braque brought to his paintings a greater interest in structure and organizing geometry than his fellow fauves, and this was strengthened in 1907, when he saw a retrospective of Paul Cézanne's works at the Salon d'automne. Braque's own painting became more concerned with construction of form, less with brilliant color and bold brushwork.

(left) Paul Cézanne, Le Château Noir, 1900/1904, Gift of Eugene and Agnes E. Meyer, 1958.10.1

(right) Georges Braque, Harbor, 1909, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Victoria Nebeker Coberly in memory of her son, John W. Mudd, 1992.3.1

Also in 1907, Braque met Pablo Picasso. Braque returned to blended color, more muted tones, and to the gradations of light and dark that model forms. He began to render forms as volumes that were essentially geometric in conception—starting on the path that would lead him and Picasso to develop analytical cubism in the succeeding years.

Georges Braque, Still Life: Le Jour, 1929, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Chester Dale Collection, 1963.10.91

Matisse

Although Matisse also moved away from the fauve style, he continued to seek harmony through color and to delight in the brilliance of Mediterranean light.

This is one of many paintings Matisse made in Nice, where he stayed for the winter months throughout the 1920s. After the fauve period, Matisse returned to his earlier interest in the human figure—often in interior scenes, often incorporating views through windows.

Henri Matisse, Pianist and Checker Players, 1924, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1985.64.25

In the last fifteen years of his life Matisse produced paper works by "cutting into color," as he said. These shapes, cut freehand and later glued onto a background, seem at once calm and dynamic.

Henri Matisse, Beasts of the Sea, 1950, paper collage on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1973.18.1