Afro Atlantic Histories: Teaching the Transatlantic Slave Trade and Its Legacies

In this portrait, French artist Frédéric Bazille presents a young Black woman, a vendor of flowers, gazing directly at the viewer. This painting conveys a sense of the woman’s individuality, with close detail given to her facial expression and her dress. Bazille lived in an area of Paris where freed Black Parisians had established communities after the abolition of slavery in 1848, and may have encountered people like the woman depicted here in his everyday life. While Black individuals may have had free status in France in the late 19th century, many still struggled to find the same opportunities for employment and advancement available to white citizens.

What do you imagine this woman might be thinking? What makes you say that? What questions would you want to ask her?

Frédéric Bazille,

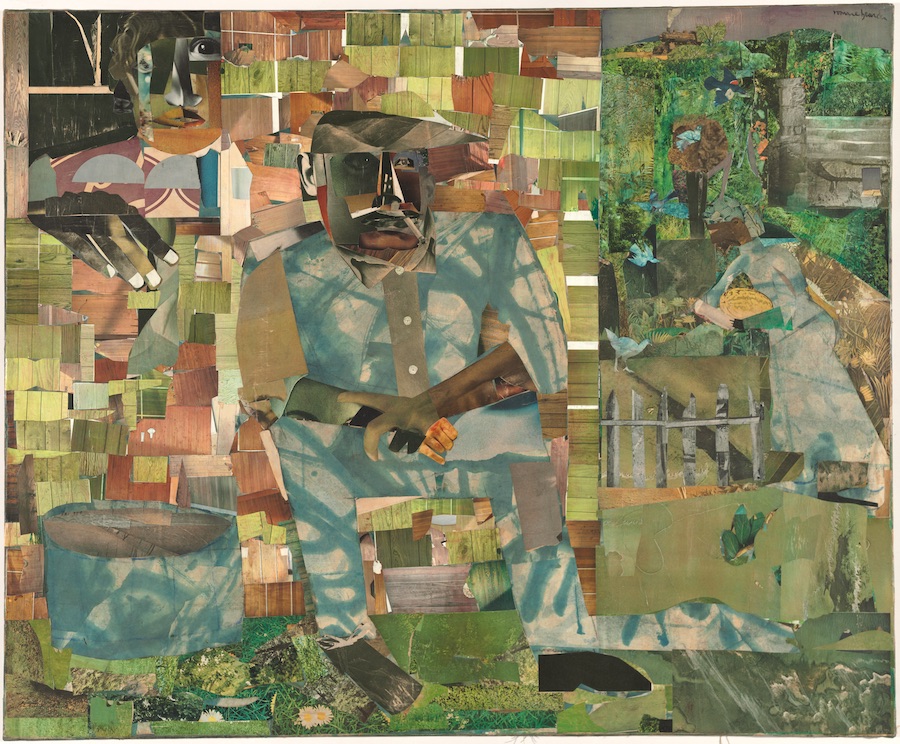

Romare Bearden was one of more than six million African Americans who fled the US South between 1916 and 1970 during the Great Migration. His family left North Carolina for Harlem, New York City, where Bearden grew up surrounded by poets, writers, and musicians. He worked as a social worker for several decades, during which time he spent nights and weekends on his art, creating collages using images from photo-magazines such as Life and Ebony.

Bearden was often inspired by music; the title of this collage is a reference to a lyric from “Good Chib Blues,” a song popularized by blues singer Edith North Johnson. The collage is rich with details suggesting memories of rural life in North Carolina: grass, a wooden fence, a watermelon. In the top right corner is an image of a train, possibly alluding to the journey of the Great Migration.

What details stand out to you in this artwork? What visual elements would you consider important to include in an artwork centered around your own family memories?

Romare Bearden,

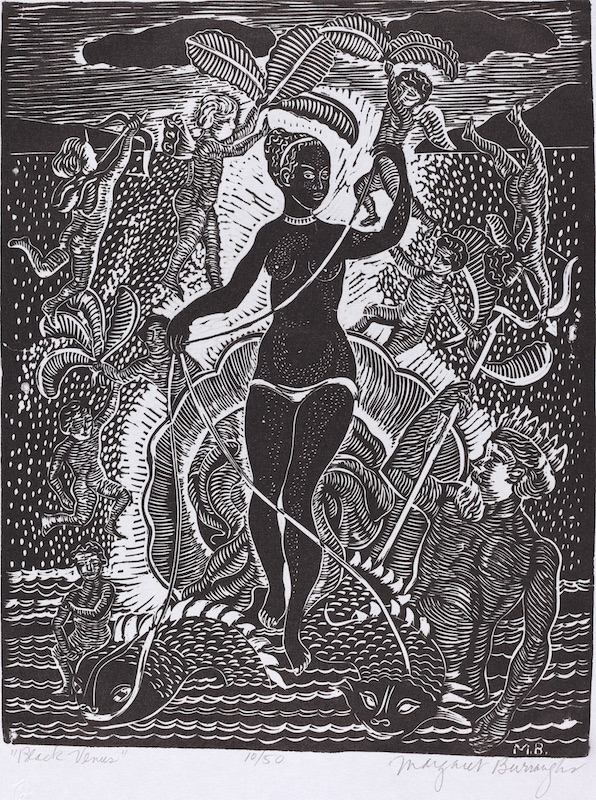

In this linocut print, artist Margaret Burroughs responds to a 1793 work by Thomas Stothard called Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies. Also a reference to Botticelli’s Renaissance painting The Birth of Venus, Burroughs’s print—made during the civil rights movement—positions a Black subject as the goddess of love, affirming the beauty and power of Black women. In addition to her artistic practice, Burroughs was an activist, educator, and fixture of Chicago’s South Side community, founding the South Side Community Art Center and the DuSable Museum.

The print’s title, Black Venus, also recalls one of the terms historically used to describe Saartjie “Sarah” Baartman, an 18th-century South African woman who was exploited for public display in Europe.

Why do you think Burroughs chose to recreate Stothard’s print? How do the two prints differ in detail and point of view?

Margaret Burroughs,

Elizabeth Catlett dedicated her art to the African American experience. She believed that “art can prepare people for change; it can be educational and persuasive in people’s thinking.”

Catlett was born in Washington, DC, in 1915, but she moved to Mexico permanently in 1946 in response to the US government’s treatment of activists during the escalating Cold War. There, she studied sculpture and made prints with the Taller de Gráfica Popular (People’s Graphic Arts Workshop) and became the first woman sculpture professor at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas (National School of Plastic Arts).

In Reclining Female Nude, Catlett emphasizes the hips and breasts of her subject, contrasting them with the figure’s small and stylized head. The artist took inspiration from both African and Mexican sculpture and positioned her work in conversation with contemporary European artists such as Henry Moore and Constantin Brâncuşi.

What details stand out to you about this sculpture? What words would you use to describe it? How might this sculpture “prepare people for change”?

Elizabeth Catlett,

Into Bondage is a powerful depiction of Africans being forcibly enslaved to be taken to the Americas. Shackled figures walk toward slave ships on the horizon, and an individual at left raises their bound hands. The figure in the center is turned toward a beam of light emanating from a lone star in the sky, possibly suggesting the North Star. The concentric circles are a motif frequently used by Aaron Douglas to suggest sound, particularly African and African American song.

In 1936, Douglas, considered a leader of the Harlem Renaissance, was commissioned to create a series of murals (of which this is one) for the Texas Centennial Exposition in Dallas. Installed in the Hall of Negro Life, his four paintings charted the journey of African Americans from slavery to the present. The Hall of Negro Life opened on Juneteenth (June 19), a date celebrating the end of slavery.

What rights had Black Americans gained by the 1930s, the time when Douglas made this mural series? What rights and freedoms did they have yet to gain?

Why do you think Juneteenth, a commemoration of the abolition of slavery, is important to celebrate?

Aaron Douglas,

In this series of lithographs, artist Glenn Ligon recreates “runaway” advertisements published in antebellum newspapers. The text of each lithograph is based on how Ligon’s friends chose to describe him if he went missing. While the descriptions focus largely on Ligon’s physical features, they also include specific notes about his personality and behaviors, as did many 19th-century fugitive notices. While running away was a form of self-emancipation for enslaved people, it did not guarantee self-determination.

As Ligon states, “Runaways is broadly about how an individual’s identity is inextricable from the way one is positioned in the culture, from the ways people see you, from historical and political contexts.”

How does the way you see yourself compare to what others think of you? What assumptions might people make when they first meet you? Are there any assumptions that you automatically make when you first meet people?

Explore the Freedom on the Move database to search for descriptions of individuals classified as fugitives. Can you find any mentions of your state in the database?

Glenn Ligon,

Théodore Géricault painted this portrait of a model in preparation for his most famous painting, The Raft of the Medusa. The model, Joseph, was a Haitian man who came to Paris with an acrobat troupe. After working with Géricault, he became a sought-after model.

This intimate study of a single figure provides an emotional look at a Black subject during a time of slavery and its atrocities. The several colors blended to depict his complexion show he was painted with great care, of a level not usually given to Black subjects at the time. While the painting is of Joseph, he was standing in for the role of a victim of the Medusa shipwreck.

The Medusa was a French ship that ran aground en route to Senegal on a mission to secure French rule over the colony and maintain the slave trade there; a shortage of lifeboats meant that only about 10 out of 150 passengers survived. Géricault’s painting of the real-life event included depictions of Black figures within the gruesome scene.

What emotions do you feel when you look at this portrait? Research how the public reacted to the disaster of the Medusa and consider what life might have been like for a Black man in Paris at this time.

Théodore Géricault, Study of the Model Joseph, 1818–1819, oil on canvas, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 85.PA.407

The artist Lois Mailou Jones often visited the Caribbean nation of Haiti, depicted here, during her life, through her marriage to Haitian artist Louis Vergniaud Pierre-Noel. In this scene of everyday life, Mailou Jones has taken care to show adults and children at work and at play, living in a dense community of brightly colored stacked houses.

Influenced by the Harlem Renaissance of her youth, Mailou Jones cultivated a lifelong interest in African and African Diasporic cultures and artistic traditions. In the 1960s, she traveled to 11 African countries to meet, learn from, and document the work of contemporary artists. Through teaching at Howard University for more than 40 years, Mailou Jones raised awareness of the contemporary artistic traditions developing in Black communities across the globe for a generation of Black artists in the United States.

What details stand out to you in this painting? How does the artist give a sense of place and identity to Haiti? How do these characteristics compare to the place where you live?

Lois Mailou Jones,

This screenprint by Jacob Lawrence is one of several works he made about the life of Toussaint L’Ouverture, the revolutionary who led Haiti in pursuing independence from France and the abolition of slavery. In this scene, we see soldiers on horseback with long coats, blue hats, and swords hanging at their sides as they ride into battle. The blur of shapes and colors heightens the drama and intensity of the action.

Jacob Lawrence, an artist of the Harlem Renaissance, was the first African American artist to have work in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in 1941. Lawrence worked as a professor and artist for decades, and heroes of African American history like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and John Brown were among his most common subjects.

What does this print tell you about Toussaint L’Ouverture and the Haitian Revolution? What new emotions or perspectives does Lawrence bring to the event?

Jacob Lawrence, Lou Stovall (printer),

Marshall’s Voyager, depicting two partially obscured Black figures standing aboard a ship, refers to an actual ship, Wanderer. The Wanderer was among the last slave ships in the United States, illegally transporting more than 400 individuals from West Africa to Georgia in 1858—even though the importation of enslaved people had been banned in 1808.

Marshall, as both an artist and professor, is known for his large-scale historical scenes that highlight subjects and events often omitted from European and North American art history. Symbolism plays a significant role in many of his paintings, and Voyager has several symbolic details, such as deceased fetuses, a skull, and vévés (geometric drawings) and the number 7, both symbols of Vodou, a religion typically practiced in Haitian Diasporic communities with both African and European origins.

Why do you imagine Marshall might have chosen this scene of the Middle Passage as his subject? Where else today can we see traces and reminders of the transatlantic slave trade?

Kerry James Marshall,

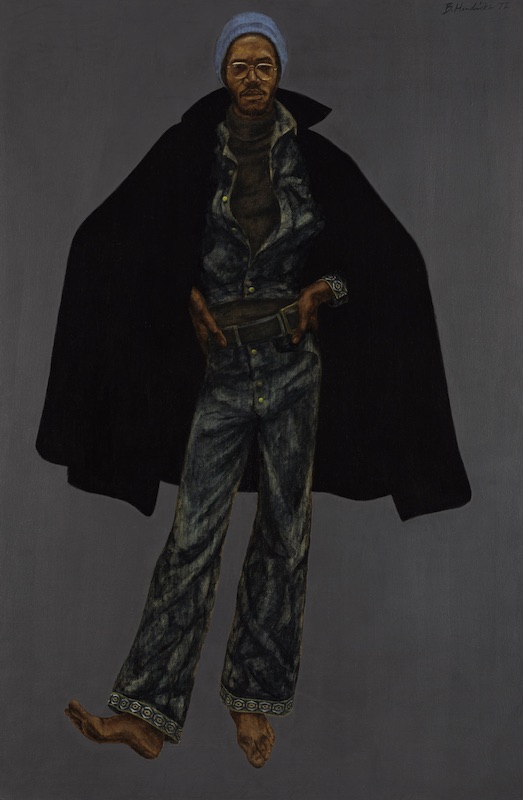

This life-size portrait depicts a young, gay Black man with a sense of confidence and style. As an artist and educator, Hendricks was keenly aware that the history of European and North American art largely omitted Black and brown subjects—a gap the artist addressed by making various members of his community the focus of his paintings. Hendricks depicts Taylor, a fellow student at Yale University, in a contrapposto stance, hands on his hips and weight resting on one leg, reclaiming a posture commonly associated with individuals in positions of power, such as gods or members of the aristocracy, in the classical tradition of portraiture.

Hendricks grew up in north Philadelphia in the 1950s and 1960s as the civil rights movement grew across the United States. His paintings and photographs convey a sense of individuality, and his work ranges from depictions of everyday people to images of well-known contemporary figures, such as jazz musicians Miles Davis and Charles Mingus.

What words would you use to describe the individual in this painting? If you could choose someone from your community to create a portrait of, who would you choose and why?

Barkley Leonnard Hendricks,

This photograph recreates a famous 19th-century painting, The Grand Odalisque, by French artist Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. The “odalisque” pose, a recurring scene in French painting, typically portrayed European fantasies of non-European women amid lush settings and objects that alluded to cultures outside of Europe. These odalisque paintings were created at a time when France was expanding its colonial empire, largely in North and West Africa.

Here, the artist Mickalene Thomas portrays her subject in a position where the phrase “only God can judge me” is visible as a tattoo on her lower back, the words reasserting control over her portrayal of the Black body.

How does this image compare to both historical and contemporary portrayals of Black women?

Mickalene Thomas,

On August 28, 1963, Alma Thomas and her friend Lillian Evans, both of whom were in their 70s, met with congregations of local churches and strode arm in arm to join the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, a famed demonstration for racial equality and civil rights where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

Thomas, whose family moved from Columbus, Georgia, to Washington, DC, in 1907, lived in the District for most of her life, as an educator and artist. She developed a distinctive abstract style of painting, and her art was typically not explicitly political. In this painting, she captures the energy of the diverse crowd, holding enormous signs of protest, highlighted with splashes of red and yellow.

How do you think it felt to participate in the March on Washington? Why do you think Thomas might have chosen to paint this event?

Watch a 1963 video documenting the March on Washington. How does this painting compare to scenes from the event?

Alma Thomas, March on Washington, 1964, acrylic on canvas, Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York

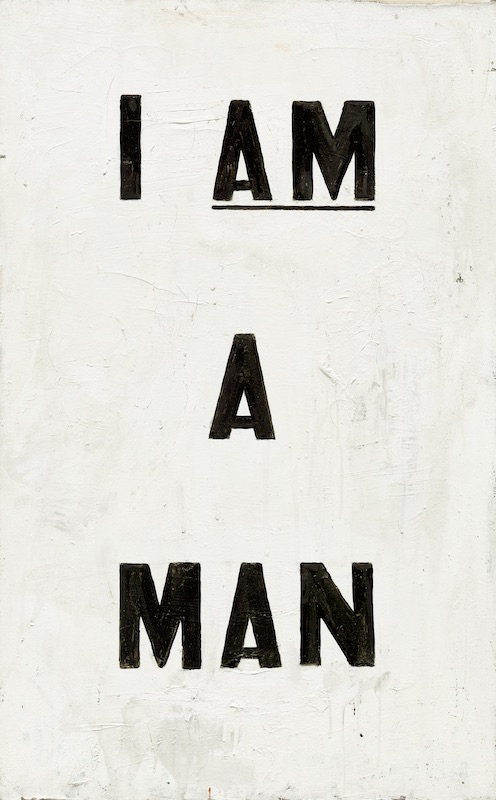

Untitled (I Am a Man) is a representation of actual signs carried by more than 1,300 African American sanitation workers on strike in Memphis in 1968. Prompted by the wrongful deaths of two coworkers from faulty equipment, the strikers—joined by Martin Luther King Jr.—marched to protest low wages and unsafe working conditions. They took up the slogan “I Am a Man,” a variant on the first line of Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man (1952): “I am an invisible man.” This slogan and these signs were used throughout the civil rights movement of the 1960s and continue to be used today.

In this work, Ligon differentiates his painting from the original, historical signs by reorganizing the line breaks and painting the black letters in eye-catching enamel. In 1988, the same year Ligon completed this painting, the Civil Rights Restoration Act was passed, expanding non-discrimination requirements for groups receiving federal funding.

Why do you think the word invisible was removed from the Ellison line to create this slogan? Do you think this artwork acts as a form of protest? Why or why not?

Glenn Ligon,

Much of artist Marilyn Nance’s work focuses on the spiritual traditions of different Black communities in the United States. In this photograph she captures Black Indians in New Orleans wearing ceremonial dress. It is popularly believed that Black Indians are descendants of Native Americans and Black Creoles, and by the 19th century, Black Indians had formed their own tribes with specific traditions, including songs and dances performed during Mardi Gras, but independent of it. Here, they wear the headdresses of White Eagles, the oldest Black Indian tribe in New Orleans’ history. The Black Indians’ traditions are an example of religious syncretism, the blending of multiple religious beliefs and rituals into a new system—common in communities of the African Diaspora.

Watch a video of the White Eagles celebrating Mardi Gras and compare Nance’s photograph to the celebration. How do they compare? Where can you see cultural blending in your own communities?

Marilyn Nance, The White Eagles, Black Indians of New Orleans, 1980, gelatin silver print, Collection of Light Work, Syracuse

Dom Miguel de Castro was an envoy from the Kingdom of Kongo (a region covering the modern-day nations Angola and Democratic Republic of the Congo) to the Dutch court in Recife, Brazil. Castro was heavily involved in peace negotiations between the Dutch and the Kingdom of Kongo while Portuguese enslavement in the area intensified in the 17th century. The Kingdom of Kongo persisted until a revolt against Portuguese rule in 1914, at which point the region was absorbed into the Portuguese colony of Angola.

This portrait of Castro is part of a group of three; the other two are smaller and portray his servants Diego Bemba and Pedro Sunda. In this painting, the artist depicts Castro with elaborate European clothing and accessories, reinforcing his position of power as a key player in diplomatic affairs.

What words would you use to describe this individual? What makes you say that? How might this image contribute to contemporary understandings of the relationships between nations in Africa and European colonizers?

Unknown Dutch, Dom Miguel de Castro, Emissary of Kongo, 1640–1644, oil on panel, Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK), National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen

McPherson & Oliver were photographer partners who documented the impacts of the Civil War in Louisiana. This photograph, their best-known image, shows the scars from whipping on the back of a formerly enslaved man widely known as Gordon. It was made in a camp of Union soldiers in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where the subject had taken refuge after escaping his bondage on a nearby Mississippi plantation.

A reproduction of this image was published in a special Independence Day edition of Harper’s Weekly with an account of Gordon’s escape. The photograph also circulated as a carte-de-visite, a small and sturdy format popular in the 19th century that allowed photographs to be easily mailed and transported. The circulation of Gordon’s portrait rallied support and raised funds for abolition and the Union.

What feeling does this image raise for you? Do you think this photograph functions as a work of activism? Why or why not? Can you think of examples of art or images from today that are used to persuade viewers on important topics? What are they?

McPherson & Oliver,

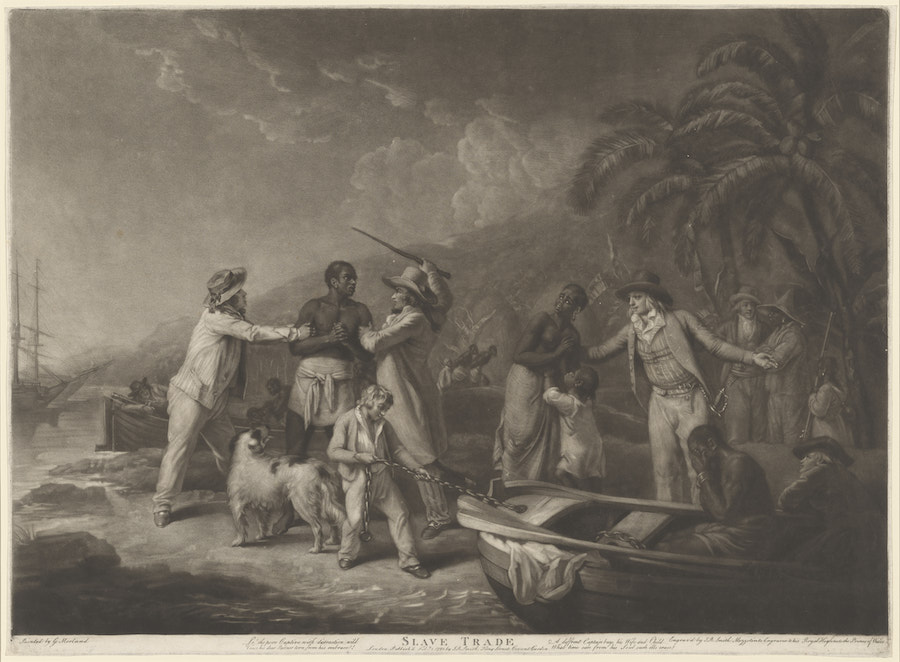

Slave Trade is a print based on George Morland’s 1788 original painting of this scene. In a setting on an African coast, a fictional African family is separated and enslaved by European sailors. Though this scene is imagined, Morland drew from descriptions of enslavement that circulated in the news at the time. Morland was among the first to produce a scene of the slave trade.

By the time Smith produced this print in 1791, the European antislavery movement was reaching a peak, and images such as this were used by abolitionists to elicit a strong response. Smith added an emotionally charged caption: “lo! The poor Captive with distraction wild / Views his dear Partner torn from his embrace! / A diff’rent Captain buys his Wife and Child / What time can from his Soul such ills erase?” The British transatlantic slave trade was banned in 1807, but it would still be decades until slavery itself was abolished in the United Kingdom.

What emotions are captured in the expressions of the individuals in this scene? What emotions do the image and its caption elicit in you? Can you think of examples of art or images from today that are used to provoke action on pressing issues? What are they?

John Raphael Smith, after George Morland,

Captain John G. Stedman’s Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition against the Revolted Negroes documents the Dutch soldier’s years in Surinam as he fought against groups of escaped enslaved people. The Dutch exploited the people and land of Surinam; when this account was published in 1796, it was leveraged by abolitionists as evidence of the horrific conditions that colonial forces and slavery had caused.

Several artists, including William Blake, created engravings for the publication based on Stedman’s drawings that depict the flora and fauna in Surinam, as well as more gruesome and violent scenes. The illustrations contrast the natural beauty of the landscape of Surinam with the cruelty experienced by Indigenous and enslaved individuals. Engravings like these laid the groundwork for later exploitative images created in the name of anthropology of ethnography.

What thoughts, feelings, or connections do these images raise for you? Who do you imagine might have been the intended audience for them?

Various Artists, including William Blake, after John Gabriel Stedman, Narrative, of a Five Years’ Expedition, against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, in Guiana, on the Wild Coast of South America (volume I), 1796, bound volume with engraved title page, letterpress text, and 41 etchings and engravings (some with stipple, one with aquatint) on laid paper, Gift of William B. O’Neal

In this imaginary scene set against the east facade of the US Capitol in Washington, DC, the goddess of Liberty, driving a chariot, leads Abraham Lincoln and his officers, who are followed by Union army cavalry. The full-bearded, sword-wielding general at the right resembles Ulysses S. Grant.

In this painting, white artist A. A. Lamb depicts a scene in which now-emancipated, formerly enslaved individuals are relegated to the background, showing gestures of gratitude toward the white figures, who occupy more central positions.

Who do you think the audience for this painting might be? Who are being portrayed as the heroes of this story? How can you tell?

A. A. Lamb,

Horace Pippin turned to art after serving in World War I in the African American regiment known as the Harlem Hellfighters. After Pippin was shot by a sniper and lost full use of his right arm, he received an honorable discharge from the military. Pippin returned to his hometown of West Chester, Pennsylvania, and taught himself to paint using his left arm to support his injured right arm.

This painting may be inspired by memories of Pippin’s childhood, depicting members of an African American family pursuing a variety of activities in a single, multipurpose room with common household items such as rag rugs, quilts, a stove, and an alarm clock. This artwork gives a glimpse into the realities of everyday life for Black families in the northern United States at the turn of the 20th century.

What feeling does this scene give you? Imagine this artwork represents the beginning of a story—what might happen next?

Read Pippin’s account of his own life. What interests or surprises you about the course of his life and career?

Horace Pippin,

Captain John G. Stedman’s Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition against the Revolted Negroes documents the Dutch soldier’s years in Surinam as he fought against groups of escaped enslaved people. The Dutch exploited the people and land of Surinam; when this account was published in 1796, it was leveraged by abolitionists as evidence of the horrific conditions that colonial forces and slavery had caused.

Several artists, including William Blake, created engravings for the publication based on Stedman’s drawings that depict the flora and fauna in Surinam, as well as more gruesome and violent scenes. The illustrations contrast the natural beauty of the landscape of Surinam with the cruelty experienced by Indigenous and enslaved individuals. Engravings like these laid the groundwork for later exploitative images created in the name of anthropology of ethnography.

What thoughts, feelings, or connections do these images raise for you? Who do you imagine might have been the intended audience for them?

Various Artists, including William Blake, after John Gabriel Stedman, Narrative, of a Five Years’ Expedition, against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, in Guiana, on the Wild Coast of South America (volume I), 1796, bound volume with engraved title page, letterpress text, and 41 etchings and engravings (some with stipple, one with aquatint) on laid paper, Gift of William B. O’Neal