Vladimír Havrilla (b. 1943) was trained as a sculptor in Bratislava in the 1960s but over the course of a long career has become a truly multimedia artist. Havrilla began making short experimental films in the early 1970s, and in the late 1970s, he also participated in performance art works with a group of friends. The 1976 film Drawings combined Havrilla’s interest in all these media and was made with the participation of three of his friends, Alžbeta Vargová, Nad’a Jarkovská, and the poet Gabriel Levicky, who now lives in the United States and describes Havrilla as “one of the most important protagonists [and] multi-faceted artists in the Slovak underground—original and daring, breaking the stifled reality of the totalitarian regime.”[1]

Banner stills L to R: Somnambulists, courtesy Filmoteka Muzeum; Drawings, courtesy Vladimír Havrilla and Boris Kršňák;

Transformations: Potter's Bull, courtesy DEFA Film Library at the University of Massachusetts Amherst

Drawings and Transformations: Potter’s Bull

Drawings

Vladimir Havrilla, Slovakia, 1976, digital file from 8 mm, 3 minutes, 30 seconds

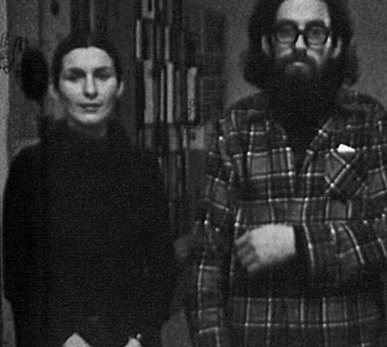

Still from Drawings, courtesy Vladimír Havrilla and Boris Kršňák

Still from Drawings, courtesy Vladimír Havrilla and Boris Kršňák

The film’s credits describe its subjects as the “3D Painters,” and indeed, the three young people spend the three-minute film drawing in the air with their hands as they pick up and continue each other’s imaginary lines. The film is very open-ended in its meaning, but it does illustrate the minimal means that artists in Eastern Europe used to great effect when working in their studios on projects that would never receive official sanction or reach a wide audience. It also shows the central role of friendship and community in the art-making process, so much so that the art here seems not a concrete end to be accomplished but an activity shared and enjoyed by like-minded people. Finally, though in no way overtly political, the film, made during the period of post-1968 Czechoslovak “normalization,” does have a social—and hopeful—dimension since it playfully shows that things that are imagined and invisible can also be real if they are part of a shared vision. For countercultural youth in Czechoslovakia that vision contained lofty ideals about political democracy and a hope for the free and open (rather than limited and clandestine) movement of ideas and people across national borders. Gabriel Levicky thus suggests that “this film is a reflection of important impacts of the global culture on us. The 60s were a whirlpool of ideas, images, sounds, motions—like a tornado effecting everything and everyone, regardless of boundaries. So in this aspect and reality, we were only partially in their prison—internally, we were free and soaring high.” — Ksenya Gurshtein

With thanks to Vladimír Havrilla and Boris Kršňák for their help in making a screening of this film possible in Washington.

Transformations: Potter’s Bull (Verwandlungen: Potters Stier)

Jürgen Böttcher, Germany (GDR), 1981, 35 mm, 17 minutes

Still from Transformations: Potter’s Bull, courtesy DEFA Film Library at the University of Massachusetts Amherst

In this poetic and visually sumptuous film, painter and filmmaker Jürgen Böttcher (b. 1931) transforms 22 postcards of the Dutch painter Paulus Potter’s iconic work The Bull (1647) by painting over them, documenting on film the process of modification that produces striking new images and brings out unexpected dimensions of the original. The film is part of the Transformations trilogy whose two other parts see Böttcher similarly transform postcards of two other old master paintings. The whole project, filmed by Thomas Plenert, a talented cinematographer, was the only avant-garde experimental film ever made at DEFA, East Germany’s official, state-run film studio.

Böttcher (who also works under the pseudonym Strawalde, the name of his birthplace) was trained as a painter at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts between 1949 and 1953. Because of his ideological differences with authorities, however—Böttcher has said that “the profession of an artist is to live life as intensively and as honestly as possible” —he was blacklisted and thrown out of the Association for Visual Arts in 1961. It was not until the 1970s that his expressionistic, abstract, and often wildly colorful paintings and drawings began to be recognized first in Germany and later abroad. Foreseeing the difficulties he would have as a painter, Böttcher studied directing at the German Academy for Film from 1955 to 1960. While painting in private, he subsequently spent his professional life as a director at the DEFA Studio for Documentary Films, where he worked until 1991. There, he directed more than 40 aesthetically provocative films and experienced both recognition as one of East Germany’s best-known documentary filmmakers and continued problems with the authorities. His first documentary, Three of Many (Drei von vielen, 1961), a portrait of three amateur, working-class painters whom Böttcher taught in an evening art class in 1955, was banned and not shown until 1988. One of the students featured in the film, Ralf Winkler, would go on to international acclaim as the painter A. R. Penck after his emigration to West Germany.

Still from Transformations: Potter’s Bull, courtesy DEFA Film Library at the University of Massachusetts Amherst

Böttcher’s only narrative feature film, Born in ’45 (Jahrgang 45, 1965), which was inspired by Italian neorealism, was also banned even before its completion because its characters were deemed “antisocial” and its representation of life in the GDR inaccurate. The censors’ anxiety about potentially subversive content in films is illustrated by the fact that in the Transformations trilogy, which to today’s eyes appears concerned only with painting, they saw negative commentary of the government’s program of building new housing estates, one of which can be seen outside the window of Böttcher’s apartment in the film.

Many of Böttcher’s documentaries reflect his artistic interests. Hermann Glöckner: A Brief Visit (Kurzer Besuch bei Hermann Glöckner, 1984) is a portrait of a pioneer of constructivism in Germany whose artistic work was suppressed for decades first under the Nazis and then under Communist rule. It is, however, the films of the Transformations trilogy that most explicitly merge Böttcher’s talents as painter and filmmaker. Along with his documentaries, these films influenced many members of the so-called Super 8 movement that was beginning to flourish in the GDR in the early 1980s [LINK]. Many of its members were artists and musicians who made short, often nonnarrative films, though they admittedly lacked access to the professional resources that give Böttcher’s films their lushness. Curiously, A. R. Penck’s amateur films of 1979, made before his emigration to the West the next year, were yet another strong influence on the Super 8 scene.[2] These facts underscore the important role that artists, most without a filmmaking background, played in pioneering film experimentation throughout the Eastern Bloc and especially in East Germany, where authorities controlled film production and education particularly stringently. In her essay “Blackbox GDR: DEFA’s Untimely Avant-Garde,” Reinhild Steingröver documents how young filmmakers in the GDR petitioned the authorities over and over for decades to create an experimental film studio at DEFA. Each time they were denied.[3] As a result, Steingröver notes, film experimentation in the GDR happened almost entirely outside the official system and “many of the participants in the Super 8 movements in various cities . . . were painters and graphic artists by training, and they often experimented in groups consisting of musicians, sculptors, writers, and their friends.” One other film from the Super 8 scene that is part of this history and that was made by Thomas Werner, who originally trained as a silkscreen printer, can be found in the City Scene / Country Scene program of this series. — Ksenya Gurshtein

With thanks to the German Federal Archive, Berlin, and to Hiltrud Schulz and Christopher Hench at the DEFA Archive at the University of Massachusetts Amherst for their assistance with the research and writing of this text and for help in making a screening of this film possible in Washington.

1. E-mail to the author, March 1, 2014. (back to top)

2. Claus Löser, “Media in the Interim: Independent Film in East Germany before and after 1989,” in After the Avant-Garde: Contemporary German and Austrian Experimental Film, ed. Randall Halle and Reinhild Steingröver (Rochester, NY, 2008), 96. (back to top)

3. Reinhild Steingröver, “Blackbox GDR: DEFA’s Untimely Avant-Garde,” in After the Avant-Garde: Contemporary German and Austrian Experimental Film, ed. Randall Halle and Reinhild Steingröver (Rochester, NY, 2008), 113. (back to top)