The Cameral Obligation in the Documents of the Accademia di San Luca

Antonia Fiori

English translation by Sabine Eiche

Premise

The cameral obligation (obligatio cameralis, or in forma Camerae) is a juridical institution that is relatively unknown even to scholars of law, but which was adopted very frequently in the Papal States in the early modern age.[1] In fact, in the Papal States, the formula of the cameral obligation was included in all contracts in which there was a financial obligation on the part of at least one of the contracting parties, but it was used in a wider sense in all the cases in which assurance and speed of fulfillment were desired.

A decision of the Rota (chief tribunal of the Holy See) in 1644 maintained that in the Papal States contracts were almost always stipulated with cameral obligations “In Statu Ecclesiastico fere semper stipulantur contractus sub obligatione Camerali.”[2] To underline its importance, we can add that the magnificence of Renaissance and baroque Rome was brought about by artists and artisans whose contracts abounded in obligations in forma Camerae.

With regard to art, the extreme relevance of the cameral obligation in regulating the juridical relationship between private individuals, or between private individuals and civic or ecclesiastical patrons, emerges with great clarity. A few examples of published contracts will suffice to illustrate this. Michelangelo Buonarroti was commissioned with cameral obligation to design the tomb of Julius II.[3] The same formula was used for Caravaggio’s contracts for work in San Luigi dei Francesi[4] and in Santa Maria del Popolo;[5] for Nicolas Cordier’s contract for the bronze statue of Henri IV of France in San Giovanni in Laterano;[6] and for Peter Paul Rubens’s contract for the high altarpiece of the Chiesa Nuova.[7] When it was feared that the dome of the Sapienza was too heavy, Francesco Borromini stood surety pledging the cameral obligation.[8]

Furthermore, the documents that have been transcribed and digitized for the National Gallery’s research project, The History of the Accademia di San Luca, c. 1590–1635: Documents from the Archivio di Stato di Roma, testify to the frequent use of the cameral obligation in the juridical relationships on which the activity of Roman artists was based.

The Accademia's statute stipulated that any “imprestanza” (loan, or commodate, which is a gratuitous loan) to the associates had to be formalized with the cameral obligation.[9] Many types of obligations were assumed in cameral form: rents, sureties, census, etc. Artists also undertook to pay the tax on evaluations in forma Camerae, paying the Accademia 2 percent of the work’s estimated value. In fact, what the statutes called the Forma della Polliza da farsi & sottoscriversi da quelli che vorranno le stime[10] is expressed in the notarial documents as cameral obligation. Among the many examples we have,[11] there is that of Guido Reni, who in 1609 promised to render 2 percent of what he was to be paid for his work at the Palazzo Apostolico, which still had to be appraised.[12] In 1607 the curate of the church of San Luca, Andrea Glacisco, after having received the inventory of the movable property in the sacristy, undertook with cameral obligation to give an account of said property whenever requested by the Accademia.[13] In 1621 the members of the secret congregation pledged in forma Camerae to comply with the brief of Gregory XV, who had confirmed the statutes of the Accademia.[14] Furthermore, the deputies of the Congregazione dei Pittori undertook with the cameral formula to celebrate intercessory masses in the church of San Luca.[15] There are many more examples that could be cited.

The essay continues with discussion of the following topics: (1) what was the origin and history of the cameral obligation; (2) who had jurisdiction over the cameral obligation; (3) what was the executio parata (forced execution of debt characterized by particular celerity) that the cameral obligation guaranteed and how was it linked to excommunication; (4) what was the role of notaries in the procedure; (5) how was it implemented. To this end we will try to point out the differences between the stylus antiquus of the obligation in forma Camerae (before 1570) and the stylus modernus, adopted exclusively in the documents of the Accademia. Finally, in the conclusion, we will indicate how to recognize the cameral formula in the notarial documents. An appendix will provide a list (not exhaustive) of Accademia documents—contained in the National Gallery of Art’s database—in which the cameral formula is given in abbreviated form.

1. Origin of the Cameral Obligation

The cameral obligation (obligatio cameralis or in forma Camerae) takes its name from the Camera Apostolica, the ministry in charge of the finances and economy of the Holy See. It was created initially to guarantee the cameral credits, which consisted mainly of annates, that is taxes on ecclesiastical benefices from around the world. The payment of these credits, fiscal in nature, was complicated for two reasons. Firstly, for the actual difficulty of obtaining a forced execution in distant regions governed by different laws. Secondly, because many debtors were not prompt in paying, preferring to wait to be condemned by three consistent judgments: after which, according to common law, appeals could no longer be presented and the decision became legally binding.[16]

The remedy adopted, to which Guglielmo Durante already alluded in his Speculum Iudiciale (c. 1290), was highly effective in solving both problems: the debtor was required to swear to fulfill within a certain period, or otherwise renounce any exception or appeal; the debtor was then warned that in case of failure to fulfill, he would automatically be excommunicated.[17] Through his bishop, therefore, the debtor could be sentenced to excommunication wherever he happened to be.

During the Council of Constance at the beginning of the 15th century, this procedure was heavily criticized for its oppressive nature, given the irrefutable disparity of power between the person imposing it and the one enduring it. It was defined as violent, against the law, even simoniacal.[18] After the Council, the payment of taxes on benefices was regulated by the church on the basis of concordats with the individual states. This led to more limited use of the cameral obligations. From the 16th century on, they appeared mainly in contracts between private individuals.

The life of the cameral obligation was long. It lasted until the beginning of the 19th century, when Pius VII’s Code of Civil Procedure of 1817 abolished the effects of the clause for the future. This provision, although confirmed by Leo XII (1824) and Gregory XVI (1831), was not included in the Regolamento di procedura nei giudizi civili of 1834, which specifically abolished the earlier codes: for this reason, still for some time after its promulgation, cases deriving from contracts stipulated with the cameral formula continued to be processed, until 1843 when it was declared definitively terminated.[19]

2. A Profitable Activity: The Jurisdiction over the Cameral Obligation of the Auditor Camerae, the Court of the Capitoline, the Tribunal of the Vicar General, and Others

The executive procedure initiated by contracts containing the cameral formula was reserved—at least in theory—to the jurisdiction of a judicial department originally part of the Camera Apostolica, which eventually became independent: the tribunal of the Auditor Camerae (henceforth A.C.).[20] It was an ordinary court with immense powers, which enabled it to exercise both the secular and spiritual gladius. Its prerogatives were first defined in 1485 by Innocent VIII, with the bull Apprime ad devotionis.[21]

Its office was composed of a certain number of judges, civil and military lieutenants, and a well-organized notarial structure that eventually comprised up to ten offices. At the end of the 17th century, after Innocent XII’s creation of the so-called Curia Innocentiana, its seat was the Palazzo di Montecitorio.

The offices of the A.C. were always overloaded with work and their most profitable activity, on which they in fact depended economically, was the writing of contracts in forma Camerae and in their forced execution. Because it was such a profitable activity, various tribunals competed with the A.C. for this privilege.

In 1513, in order to protect its prerogatives, Leo X indicated the cameral obligations as the exclusive jurisdiction of the A.C. In the motu proprio Iniunctum, he cautioned all other judges against having anything to do with them, under pain of excommunication or monetary penalties.[22] There was to be only one exception. If questions inherent to a cameral obligation arose in the course of a different trial, then it was allowed that the contract could be executed in that same jurisdiction.

Leo X’s intervention did not prove very successful. He complained just a few years later that the exclusive jurisdiction of the A.C. continued to be undermined through various pretexts.[23]

Other pontifical measures were therefore necessary. Pius IV dealt with the matter in 1561 with the bull Ad eximiae devotionis[24] and in 1562 with the bull Inter multiplices.[25] For the first time, he spoke expressly of a privativa (exclusive jurisdiction) over cameral obligations and granted a special privilege to Roman citizens.

In general, on the basis of what Sixtus IV established in 1473, the court of the Capitoline had jurisdiction over the inhabitants and secular citizens of Rome, and the court of the Papal Vicar over the Roman clerics.[26] The cases of cameral obligation were nevertheless reserved for the A.C.

Pius IV instead gave Romans the possibility of asking for the execution of obligations in forma Camerae at the Capitoline court. The privilege, already granted with the motu proprio Dilectos filios senatorem[27] and confirmed with Ad eximiae devotionis,[28] was initially appended to the 1567 edition of the Roman statute and, then, beginning with the Gregorian statute of 1580, its regulations were merged in chapter 41 (De foro competenti) of Book I.

The privilege of Pius IV was a clear sign of respect for Rome and was confirmed by successive pontiffs. All the same, according to Giovanni Battista De Luca, Romans continued to prefer the highly specialized A.C. for the cameral obligations.[29]

Pius V instead extended jurisdiction over cameral obligations to the tribunal of the Vicar. Initially it was done with the motu proprio Considerantes of 1566, with regard to the clergy and to loca pia.[30]

He returned to it at the time of the reform of the tribunal of the A.C., introduced on November 20, 1570, with the motu proprio Inter illa.[31] While recognizing the exclusive competence of the A.C. regarding the cognitio and executio of the cameral obligations, it established that debtors who were secular Roman citizens could appear before the Capitoline court, whereas the principle of praeventio between A.C. and office of the Vicar would be applied to clergy, whether Roman through birth or benefice: in other words, the first assigned judge would have been able to proceed with the case.

Paul V confirmed this regulation with the constitution Universi agri dominici (1612).[32] According to common opinion, the regulation represented the definitive codification of the material. All the same, after 60 years, the jurisdiction of the Vicar on the cameral obligations started to become the subject of shifting reforms. This situation persisted until 1742, when Benedict XIV, with the constitution Quantum ad procurandam, returned the jurisdiction of the Vicar within the limits fixed by the reform of Paul V.[33]

Therefore, as far as the cameral obligations contracted by Roman citizens were concerned, the tribunal of the Vicar was the relevant one for the clergy, and the tribunal of the Senator (the Capitoline court) for the secular cives (citizens).

The orientation of the jurisprudence of the Roman Rota is to be added to the papal measures regarding jurisdiction over cameral obligations. Over the course of the 17th century, the Roman Rota further limited the exclusive jurisdiction of the A.C. within the Curia, substantially preventing the A.C. from reinstating cases of cameral obligation that had been brought before other tribunals extra Romanam Curiam.

The exclusive jurisdiction, ultimately, was little respected: it was violated by the tribunal of the Camerlengo and the Camera Apostolica, “prorectors and judges of the basilicas, hospitals, churches, congregations, and pious places,” the magistrates of the guilds and merchants without having any right. And the cameral obligations entered into by prisoners were dealt with by the President of Prisons also after their release.

Even the Reggente of the Cancelleria considered himself as an ordinary judge in the cases of cameral obligation. Furthermore, the jurisdiction of the A.C., undercut by other Roman judges, was contested also by the Congregazione del Buon Governo, which ended up taking care of the cameral obligations in cases involving debts contracted by the municipalities.[34] In conclusion, it seems that both within and outside the city of Rome, the cameral obligation could be handled by any judge.[35]

Among the great number of acts collected on the site The History of the Accademia di San Luca, c. 1590–1635 are numerous instrumenta with the formula of cameral obligation rogated (written to be legally binding) by Capitoline notaries.[36] As we saw, Roman citizens could request the execution of cameral obligations from either the A.C. or the Capitoline Curia. We cannot, however, exclude that part of the Accademia’s cameral obligations were handled by the Vicariate given that, as a congregation and in accordance with the Tridentine regulations, it was entrusted by Gregory XIII to the jurisdiction of the Vicar from the start.[37] We also know that in 1606 the Cardinal Vicar Girolamo Pamphili had nominated the jurist Guazzino Guazzini as judge in cases involving members of the Accademia, without however referring expressly to cameral obligations.[38]

3. The Executio Parata of Cameral Obligations and Excommunication

But what, in effect, did the obligation in forma Camerae consist of?

The cameral obligation started out as a specified series of clauses attached to a contract. The clauses, as a whole, constituted a “formula” to guarantee certain safeguards, above all celerity of execution. In addition, there was the special guarantee of access—either jointly or severally—to an execution against property, a personal execution (incarceration), even a spiritual execution (excommunication).[39] Taken together, these three forms of execution made the cameral obligation an unicum within the larger category of executive instruments of the early modern age, to which it belonged due to the so-called executio parata (a forced execution of debt characterized by particular celerity).[40]

The formula of executio parata rendered the contracts enforceable titles particularly secure for the creditor. In case of noncompliance, it was not necessary to have the credit confirmed by an ordinary civil proceeding; in other words, it was not necessary to verify the situation actually existed between the parties, which was not considered controversial. The possibility of opposing the execution by presenting exceptions or appeals was thus drastically reduced by the debtor’s declared renunciation of the right to do so.

In the Papal States, the cameral obligation was the true cornerstone of the process of execution. It established the “first and most frequent and most privileged” procedure, to quote the great jurist Giovanni Battista De Luca.[41]

Generally speaking, and taking into account that modifications were introduced over time, the cameral obligation required the debtor to:

- obligate himself and his heirs, and bind and mortgage all his and his heirs’ assets and property, present and future;

- submit to any jurisdiction, and principally to the specific one of the A.C.;

- consent in advance to excommunication and to personal execution (incarceration) up to the full settlement of the credit;

- renounce resisting the execution in any way;

- swear to observe and not revoke what is stated in the instrument.

The other executive instruments used in the medieval period and early modern age (such as the guarentigia, strumento sigillato or confessionato, penes acta obligation, etc.), although in different ways very similar to the cameral obligation, were effective “only” with regard to the patrimony and personal freedom of the debtor.[42] Transforming the defaulting debtors into excommunicated sinners was an additional and very powerful weapon: it signified not only striking them deep down in their faith, but also destroying their social life. The major excommunication, in fact, separated the debtor from the communion of the church and from the faithful, who were obliged to avoid him. For example, if the debtor was a merchant, the social and commercial consequences could be very serious. According to the stylus of the Curia, bishops, archbishops, patriarchs, and cardinals could not be excommunicated without express mandate of the pope.

Excommunication for debts was a widespread practice in many European countries, at least until the 16th century.[43] Outside the Papal States, it could be imposed exclusively in the ambit of ecclesiastical jurisdiction, but it struck the secular population extremely frequently.

Juridically, it was based on two conditions. Above all, it was based on the widespread use of confirming contracts and transactions by way of sworn clauses—that is, containing the promise of execution and the sworn commitment not to revoke the contract itself. As for res spiritualis, the oath transferred the contractual material from the competence of civil judges to that of the ecclesiastical judges, regardless of the purpose of the contract.[44] The situation was opposed by the nascent national states in the early modern age, but by the mid-15th century, the celebrated French jurist Guy Pape could affirm that the oath was used in all instruments of obligation (“in omnibus instrumentis obligatoriis adhibetur iuramentum.”[45])

Therefore, once they were subject to ecclesiastical jurisdiction, the debtors could face excommunication due to their contumacy, understood as contemptus: that is “contempt, scorn, defiance, obstinacy, presumptuousness.”[46] The failed compliance of an order to fulfill was in fact considered “contumacious” disobedience and, according to the rules of canon law, contumacy was the prime cause of excommunication.[47]

The indissoluble relationship between cameral obligation and excommunication was furthermore linked to a disruption of the ordinary iter of execution, which allowed the debtor to be excommunicated immediately, and then to be prosecuted subsequently also with an execution against property and/or personal execution, jointly or severally, depending on the creditor’s preference. In other words, the execution against the debtor’s assets came last. Instead, the ordinary executive procedure began with the enforced expropriation of movable assets, then immovable assets, then the assets of the guarantors, to progress finally to the personal execution.

The Council of Trent radically changed the configuration of the cameral obligation, modifying its main characteristic. If excommunication previously took precedence over other forms of enforcement, the Tridentine decrees in the 25th session of the reform had established a criterion of moderation in imposing excommunication, stating that for civil cases it could intervene only in the case of difficulty of personal enforcement or foreclosure.[48] Therefore, it was now the imposing of excommunication that came after the execution against freedom and property.

In 1570 the constitution Inter illa of Pius V adopted the decree of the Council of Trent, and beginning with this disposition the cameral obligation entered the second phase of its history, the “modern” phase.[49]

4. The Notaries

The broad diffusion of the cameral formula in contracts and the speed of the procedure created an enormous amount of work that, in effect, fell almost entirely on the shoulders of the notaries.[50] They often carried out the work of the judges, who in some cases did no more than sign their names on a blank sheet, which the notaries then transformed into judicial decisions. Sallustio Tiberi said, with reference to these judgments in particular, “notarii debent esse oculi Iudicis” (notaries should be the eyes of the judge).[51]

The procedure in forma Camerae started in the presence of a notary. In rogating a contract of a mortgage, a lease, a census, or in any case relating to a monetary obligation, the notary inserted the typical clauses, which allowed the executio parata. His work accompanied every step of the executive procedure.

Unlike instruments with a clause of guarentigia, which already contained the act of precept, in the case of cameral obligations no jurisdiction was formally delegated to the notary.[52] The executive mandates were under the jurisdiction of the judge and papal legislation did not foresee exceptions to this principle. The intense and repetitive routine of the execution of obligations in forma Camerae, however, made it impossible that every judicial decision necessary to complete the various phases of the procedure could be effectively carried out by the judge according to the required formalities.

Therefore, the majority of the acts were in fact completed by the notaries of the tribunal.[53] Only in special cases, in which the intervention of judicial authority was absolutely indispensable—for example, when issuing definitive decrees—was the requirement of the written form ad nullitatem (i.e., without which the act is null and void) fulfilled by the signature of the judge below the annotation which the notary had made in his broliardo, the Liber actorum notariorum.

Over time, the stylus of the tribunal regarding the execution of the cameral obligations underwent substantial modification. The most significant changes resulted in an increased autonomy for the actuary notaries (that is, the notaries of the tribunal), which meant that the auditor, for his part, had to place an increased trust in them.[54]

Indicative of this great trust was the fact that the A.C. and his civil lieutenants regularly signed documents that only subsequently were transformed by notaries into judicial decisions. In practice, therefore, it was the notarial offices that issued—depending on the requirements—warnings or executive mandates, even ecclesiastical censures, without having to turn to the judge again.

Where possible, the notary guided the procedure, integrating the missing elements. In time, the integrations became permanent and conformed to a style.

For example, the imposition of censures initially occurred by means of a formula, written by one of the judges of the tribunal in his own hand below the obligation or added to the notary’s annotation in his broliardo. With the passing of time, however, it became established for judges, during any audience, to limit themselves to signing what the notary had written in his broliardo.[55]

Similarly, the notary would (falsely) indicate the procurator’s confession of debt—which was supposed to have taken place before a judge of the A.C.—together with the procurator’s presence at the time the contract was concluded, as having occurred, when in fact these requirements were evaded in order to avoid a chaotic situation in the already crowded offices.[56]

It was, in the final analysis, the practical needs that actually determined the proceedings, and it was up to the notaries to address them accordingly. The judicial functions of the tribunal were in fact shared with its actuary notaries, although not assigned to them formally.

5. The Procedure before and after 1570: Stylus Antiquus and Modernus

As mentioned above, in the long history of the cameral obligation, there is one date that marks the end of a way the formula was used and the passage to a new way: 1570, when Pius V’s constitution Inter illa introduced the disposition of the Council of Trent relating to excommunication. In civil cases, excommunication could only be imposed in iuris subsidium—that is, when it is not possible to proceed to an execution against property or a personal execution.[57]

The procedure of the execution of the cameral obligation in use until circa 1570 was called the stylus antiquus. The passage to the stylus modernus occurred formally with the constitution Inter illa, but in reality the transition was not abrupt because the innovations had been preceded by a debate among jurists regarding certain questions, and some of them had already been effectuated in practice.[58] The new form of the cameral obligation was secured by the constitution Universi agri dominici (1612), in which Paul V recommended that the stylus hodiernus be observed in the execution of the cameral obligations. It differed from the outdated forma antiqua in several ways, which were indicated by the pope: (1) the possibility of a single summons; (2) the obligation regarding the heirs; (3) the failed appearance of the procurators; (4) the lack of the susceptio censurarum.[59]

It is worth emphasizing that, after 1570, the two styles never coexisted; the most recent style supplanted the old one. In the second half of the 17th century, De Luca could therefore write that the old formula was “in totalem oblivionem habita” (lives in total oblivion). According to De Luca, the modern formula of the cameral obligation, characterized by a greater range of clauses (“maiorem clausularum amplitudinem”), had resolved all the interpretive doubts that the old formula had left open, and it avoided the possibility of new doubts arising.[60] Above all, it simplified the procedure because it abolished superfluous formalities which served only to support dilatory strategies and were therefore a hindrance to commerce.

The many cameral obligations that we find in the notarial documents relating to the Accademia di San Luca, conserved in the Archivio di Stato di Roma, belong to the period after 1570: they therefore follow the stylus modernus. They are recognizable as such because for the most part the acts concern obligations in ampliori forma Camerae, an expression indicating the use of the modern style. Furthermore, they refer to the responsibility of the heirs. For greater clarity, we shall therefore describe the executive procedure connected with the obligation in forma Camerae, explaining the particular characteristics of the stylus modernus, occasionally referring to what the procedure had been before the reform.

a. The Instrument: Repetitio, Recognitio and Extensio Formulae before and after the Reform

The obligation in forma Camerae could be found in a public as well as a private instrument. The public form was not necessary for the contract to be valid, but it permitted a swifter execution.

Naturally, the greatest degree of certainty, and therefore of trustworthiness, was provided by the public instrument rogated by an actuary notary.[61] It was also customary for the notarial offices of the A.C. to append the clauses of cameral obligation in most contracts involving a monetary obligation, to the point that in the Papal States, the cameral formula was presumed to have been affixed, even when not expressly indicated. There were few exceptions: for example, in Bologna, where it was not customary to oblige in forma Camerae.

Furthermore, if the contract had been rogated by an actuary notary, it was presumed that the clause was not only affixed, but also correctly drawn up. Therefore, it was not required to verify the act, and the debtor could be summoned immediately.

According to the stylus antiquus, however, if the instrument had been rogated by a different notary, it would have to be produced before an actuary notary, who could limit himself to carrying out a repetitio before moving on to the summons. Or, if the first notary had in some way abbreviated the clauses, which happened often, or if it was a private instrument, the actuary notary would have to have proceeded to the so-called extensio of the formula in order to make the instrument conform in every way to the cameral obligation in use. For this purpose, the notary had to carry out a recognitio, also by way of the sworn testimony of witnesses.

The extensio consisted in the insertion of all the general clauses considered essential in the contract in forma Camerae (with the exception of the oath), and the Roman Rota regarded it necessary under pain of nullity.[62] It was followed by the A.C.’s decretum de extendendo.

The extension was much discussed. It was the source of dispute regarding procedures for enacting it and the occasion for dilatory strategies on the part of the debtor. De Luca considered it an example of those “useless formalities of which antiquity was so fond.”[63]

In fact, the stylus modernus, which called for a swifter procedure, had in part abandoned it: whoever had obliged themselves in ampliori forma Camerae (that is, according to the modern stylus) with a public instrument—even if not rogated by notaries of the A.C.—would not need to be summoned by the extensio of the formula. It sufficed for him to have agreed to the executive mandate unica vel sine citatione (with a single summons or without), and in this case he was summoned only once, directly ad solvendum (for the fulfillment). The possibility of avoiding the extension did not regard contracts in private form, and it was excluded if there was a change in the subjects of the obligation (personae mutatae).

b. The Summonses

Once the instrument was verified, the debtor was summoned. Normally the summons of a debtor who resided in Rome was delivered personally (personaliter) or through posting (per affixionem cedulae) on the housedoor. In the first case, the summons could be for the same day (hodie per totam, that is at the time of the hearing), in the second, it was for the following day (ad primam).

If the debtor did not reside in Rome and turned out to be absens, then the creditor, after a brief search, swore in the city to the absence of the debtor, and the oath in itself constituted proof of the absence. However, in order to proceed in absentia, the credit had to be liquid—that, is the total amount had to be established. If not, it would have to have been established by witnesses prior to the taking of the oath.

In this case, the summons could take place per audientiam contradictarum, if it happened to be the period of hearings, or per affixionem on the door of the Curia of the auditor or in some other usual place, if it happened to be the period of vacatio. The audientia contradictarum was a type of summons used with regard to all contumacious absent from Urbe (“omnes contumaces ab Urbe absentes.”)[64] The summonses were read by the notarius contradictarum in a public place during the dies iuridici (i.e., the period of hearings); during the tempus vacationum, the contradictae were instead posted.

Under the stylus antiquus, the debtor received several summonses. If the obligation was inserted in an act that required the extension of the formula, the debtor was summoned ad dicendum contra iura. In the actual executive phase, the summons of the debtor occurred firstly in the ways just described; a second time with excommunication and the issuance of the litterae declaratoriae; a third time for aggravation, re-aggravation, and invocation of the secular arm; and a fourth time for the initiation of forced execution.

The procedure was carried out at an extremely fast pace, so that—if the debtor resided in Rome and was praesens (present), and deferment had not been granted—it took 15 days at the most to arrive at the stage of enforced expropriation. The actions that were carried out during the course of this brief period were numerous, even relentless, for the debtor. All in all, the debtor’s presence was requested for two specific purposes: to discharge, confess, or see the debt confessed and to be excommunicated.

If the debtor obliged himself according to the stylus modernus, consenting to the executive mandate unica vel sine citatione, he was summoned only one time, directly ad solvendum. Once the debtor appeared in court, he received the notice to comply. Provided there were no relevant exceptions, the executive mandate was released at the same time. If instead the debtor had agreed to a bina citatio (double summons), the mandate would have been released in the second and final hearing.

c. Confession of Debt and Excommunication

Confession of debt and excommunication characterized the stylus antiquus. Once the time limit imposed by the first summons had elapsed, the confession of the debt was carried out at the request of the creditor by one of the procurators indicated in the instrument for the amount stated in the same instrument.

After the confession of debt had been carried out at the request of the creditor, the judge declared that if the debtor had not complied within three days (nisi infra tres dies), he would be sentenced to excommunication. However, within that three-day time limit, he had the possibility of raising relevant objections from among the few conceded in the obligation in forma Camerae.

Assuming that the three days passed without fulfillment (although the deadline could be delayed for up to 30 days), the judge, in the presence of the creditor or his procurator, declared the debtor excommunicated if he had failed to comply by the end of that same day. If the day passed without any steps being taken, the so-called litterae declaratoriae were issued. The declaratoriae were not needed for the commination of excommunication (which had already been declared with the formula nisi infra tres dies satisfecerit), but rather for its publication and the social consequences it entailed. As is known, whoever was excommunicated was forsaken by the faithful.

It is worth underlining that the tres dies indicated by the judge were equivalent to the triple admonition (trina monitio) requested by canon law before imposing the excommunication. In this way, the two juridical bases of excommunication—contumacy and monitiones—were formally preserved.

The declaratoriae were written by an actuary notary, delivered to the plaintiff, and posted by a cursor (process server) of the tribunal in Campo de’ Fiori to make it publicly known that the debtor was excommunicated. If ten days passed without fulfillment, the debtor was summoned another time for aggravatio, reaggravatio, and auxilium brachii saecularis. Essentially, at the hearing, the judge increased the censures, invoking the aid of the secular arm, and issued the “aggravatory letters.” These letters contained both the order to obtain goods from the debtor’s patrimony to the value of the debt with the intention of selling them at auction and to incarcerate the debtor until the entire debt was fulfilled.

Pursuant to these letters, notices written in capital letters were posted around the city. Images deformed and unseemly (“deformes atque indecorae”) were drawn in various colors at the tops of the notices, vilifying the debtors.[65]

The stylus hodiernus no longer required the constitution of the procurators for the confession of the debt (ad confitendum debitum). It was a significant transformation of the procedure because up to that moment the confession in court of the debt (confessio in iure), a very old element of the cameral obligation, had been decisive for its validity. The constitution Inter illa had established instead that the procurator could be appointed for the confession of the debt only if he had been nominated by the defendant also for his defense and had not accepted the request. The disposition had been confirmed by the bull Universi agri dominici in 1612. In the same year, Sigismondo Scaccia attested that the constitution of the procurator had by then disappeared from judicial practice. Furthermore, the judicial confession of debt had disappeared. Scaccia maintained that if, after the reform, there was still trace of it in instruments provided with the cameral obligation, it would most likely have been fictitious.[66]

d. Execution against Property and Personal Execution

After excommunication (according to the stylus antiquus), or before or in its absence (according to the stylus modernus), it was possible to proceed against the debtor with an execution against property and/or personal execution, jointly or severally, depending on the creditor’s preference. The debtor had the power to avoid or halt the executive procedure at any time by consigning the amount owed, in cash, to the executors.[67]

The personal execution led to incarceration and in theory could apply to any debtor. In fact, it affected the most defenseless social classes because judges customarily spared prelates, barons, illustrious men, and “honest women” from being arrested.[68] Imprisonment ceased only after paying the debt (soluto debito), or after the deposit of appropriate bail.

The execution against movable property occurred by seizing the property from the house of the debtor (or from another place) and its deposit. Following the institution by Urban VIII in 1625, the seized property was deposited at the Depositaria urbana dei pubblici pegni.

In the case of immovable property, seizure was carried out by way of accessio ad domum and potentially ad vineam (entrance into the house or vineyard) of the debtor, in the presence of witnesses, the executor, and the actuary notary of the lawsuit, who wrote the minutes.

Once seizure of the movable and immovable property was completed at the request of the creditor, the debtor was summoned to receive the order to consign the money in partial or total fulfillment of the credit, by decree nisi ad primam diem, that is within one day. If the brief time limit elapsed without response, the executors received the mandate to consign the properties to the cursors for sale at auction.

Having received the goods, the cursors described them in a voucher and then arranged for the auction. After the goods were sold to the highest bidder, if the creditor considered the proceeds insufficient, it was customary for the Curia to move ahead to a further execution—either against property or personal execution—pursuant to the first mandate, until the credit was fully repaid.

e. The Exceptions and Vulneratio

The formula of the cameral obligation called for the invocation of exceptions and appeals to be renounced. All the same, it was generally accepted that three exceptions—falsitas, solutio, and quietatio—could serve to oppose the cameral obligations. These were not peremptory, however. Others were allowed on the basis of their relevance, but above all on the condition that they did not obstruct or delay execution.

Certain exceptions could not, in fact, be evaded: the ones based on the incompetentia iudicis, on the inhabilitas of the plaintiff (for example, because he was a minor, exiled, or excommunicated) or on his nonfulfillment (res non tradita, pretium non solutum), and on the nullity of the instrument.

In general, according to doctrine and jurisprudence, a few exceptions could simply be rejected; others delayed the prosecution of the process because their admissibility was immediately evident from the reading of the instrument, by known fact, or by the nature of the thing (for example, res non tradita, res non libere tradita, etc.). Exceptions that were not immediately ascertainable but required further research, for example for witnesses, could be rejected in order not to delay the execution.

This general criterion left space for a casuistry of admissible exceptions. The execution however always had to be interrupted in case of vulneratio, that is to say when a debtor’s sentence or an arbitration ruling of acquittal intervened. The vulnerata obligation lost the executio parata and always became open to appeal. The appeal, however, constituted the only recourse for the creditor, who then had to wait for the three consistent judgments.

It was with some hostility that not only writers of treatises but also the law regarded the hypothesis that a certain event—even a fact as important as the acquittal of the debtor—could obstruct or interrupt the executive procedure. De Luca did not disguise the fact that he considered the acquittal a “serious injury” to the creditor and warned the judges “not to be uncertain and easy to absolve.”[69]

f. The Obligation with Regard to the Heirs

At the time of the stylus antiquus, it was debated if the cameral obligation would be transferred to the heirs.[70] It was uncontested that the obligation would be transferred in its entirety to the heirs of the creditor. However, there were many doubts regarding the heirs of the debtor, above all because the cameral obligation consisted of a sworn obligation and the heirs would have perjured themselves for an oath that they had not personally sworn, or would even have incurred excommunication. But the question that seemed central and a hindrance to the transmission of the obligation to the heirs was that of the mandate to the procurators.

The cameral formula, according to the stylus antiquus, in fact included the constitution of procurators, with the mandate to confess the debt in the name and on behalf of the debtor for the amount indicated in the contract, and it was deemed that the mandate must be considered revoked upon death of the debtor. Nonetheless, in the mid-16th century, the Segnatura di Giustizia had reached the conclusion, which was then adopted as standard practice, to consider the properties of the deceased debtor executable since the mandate, being inserted in the cameral contract ad alterius commodum (i.e., for the benefit of the other party), could not be tacitly revoked upon death of the debtor.[71]

In the following years, after the reform of the cameral obligation of 1570, the solution indicated by the Segnatura di Giustizia was reinforced by the failure of the constitution of the procurators. Therefore, the transmissibility to the heirs, on which the doctrine had hesitated since 1555, proceeded to become a typical feature of the stylus modernus. It was indicated as such in the constitution Universi agri dominici (1612).

6. Conclusions: The Certainty of the Formula, the Disadvantage of the Debtor

The great fortune of the cameral obligation was based on the fact that it allowed for a very swift execution, freeing the creditor not only from waiting for the conclusion of an ordinary process, that is the verification of the debt, but also from any delay deriving from the opposition that the debtor could have raised in the realization of an ordinary procedure of execution.

It was an entirely preferential execution, whose swiftness and efficiency, however, were completely to the disadvantage of the debtor. He swore to comply, making himself liable to perjury and pledging not only all his properties, present and future, but also the present and future properties of his heirs, his personal freedom. He even risked excommunication. He subjected himself to the jurisdiction of any judge and accepted that the executive mandate against him was issued immediately following a single summons. He renounced obstructing the execution not only with exceptions and appeals but also with any advantage foreseen by the law, and—except in the extremely rare case of acquittal—he could avoid execution only with fulfillment.

In assuming such a serious obligation, he was not always well informed of the responsibilities deriving therefrom; in their instruments, notaries habitually abbreviated the formula of the cameral obligation to the point of rendering it incomprehensible and unrecognizable for anyone who did not already know it. If Antonio Massa, in the 16th century, maintained that the cameral obligation was known to all, including women and peasants, in reality—and in time—the fact of taking for granted information regarding the gravity of the obligations that had been entered upon became increasingly vexatious for the debtor.[72] Beginning in the 18th century—by which time the cultural and judicial climate regarding the cameral obligation had changed dramatically—this aspect was often denounced and lamented by jurists: the notaries informed the parties, and particularly those assuming the obligations in forma Camerae “with the greatest circumspection.”[73]

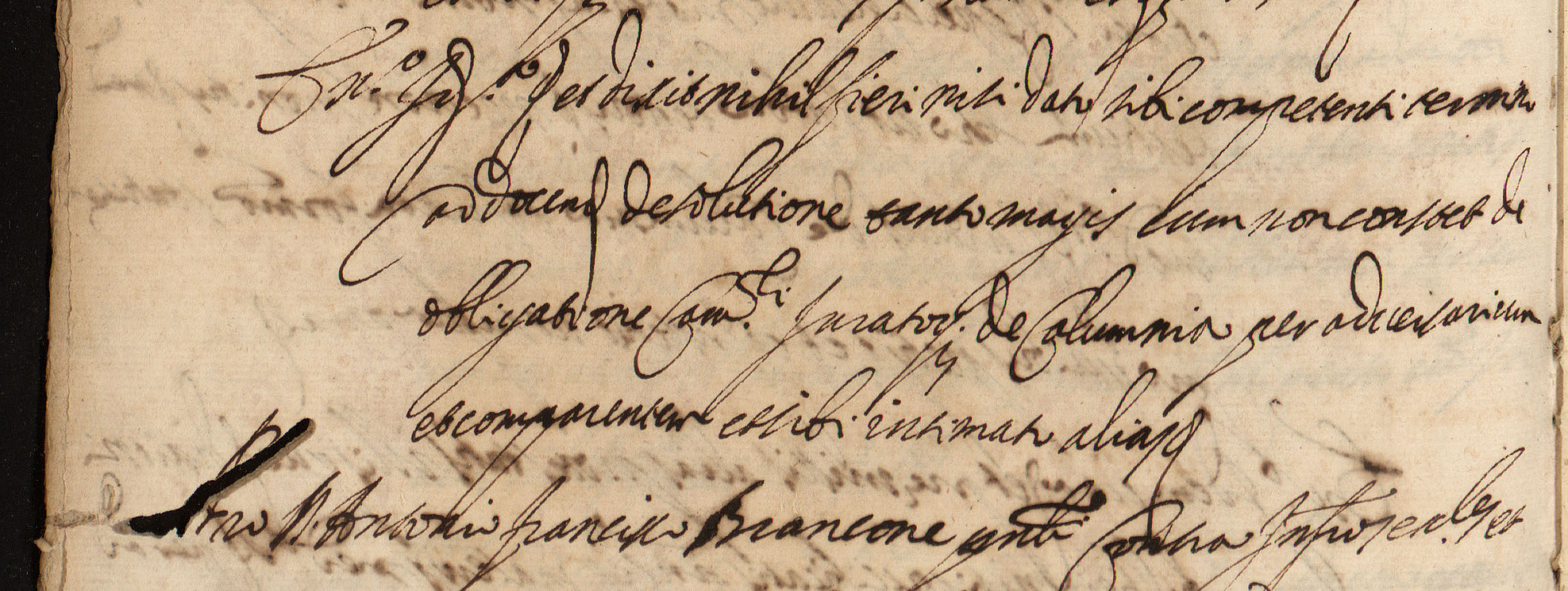

Considering that the notaries’ habit of radically abbreviating the formula—also in the numerous documents of the Accademia di San Luca that have been digitized and transcribed for this project—makes it difficult to recognize the cameral obligations and their content, it seems useful to provide some suggestions for identifying them.

Below are brief indications for recognizing the formula of the cameral obligation in the notarial instruments of the Accademia (and for facilitating research in the database of The History of the Accademia di San Luca):

- the incipit of the formula is always Pro quibus;

- the formula has the expression in forma Camerae Apostolicae, but often, for obligations in the stylus modernus (after 1570), the wording used is in ampliori forma Camerae: this would imply that, unless the parties have agreed otherwise, the obligation will be transferred to the heirs also ex parte debitoris;

- for this reason, reference is made to haeredes and bona;

- the formula is always abbreviated cum clausulis solitis etc.;

- waivers (to appeals, exceptions) are indicated;

- the consent to a single (unica) summons is indicated;

- the formula closes with reference to an oath.

In other words, allowing for minor differences between one notary and another, the abbreviated formula was approximately as follows:

Pro quibus etc. se etc. heredes etc. bona omnia etc. in ampliori forma Camerae Apostolicae cum clausulis solitis etc. citra etc. renuncians etc. obligavit ac mandatum etc. unica etc. et tactis iuravit Super quibus etc.

In content, this abbreviation corresponds to the following formula of the stylus modernus of the cameral obligation, for which reference is normally made to the text published by Silvestro Zacchia in the Lucubrationes ad Gallesium de obligatione Camerali, quibus praeter additiones eiusdem Authoris . . . accesserunt aliae Lanfranchi Zacchiae I.U.D. (Rome, 1647):[74]

Pro quibus omnibus, et singulis praemissis tenendis, complendis et inviolabiliter observandis idem A. debitor se ipsum, suosque haeredes, ac successores quoscumque, ac bona sua, et suorum quaecunque tam praesentia, et futura tam mobilia quam immobilia, ubilibet existentia iura, actiones, et debitorum nomina in ampliori forma Camerae dicto B. praesenti, et acceptanti, et pro se, suisque haeredibus, et successoribus quibuscunque stipulanti, et recipienti obligavit et hypotecavit, nec non Curiae causarum Camerae Apostolicae eiusque Camerarii, Vicecamerarii, Auditoris, Viceauditoris, Regentis, Locumtenentis, et Commissarii, ac omnium et singularum aliarum Curiarum Ecclesiasticarum, et secularium ubilibet constitutarum iurisdictionibus, coercionibus, compulsionibus, iuribus, rigoribus, stilis, et meris examinibus supposuit, et submisit, per quas curias, et earum quamlibet tam coniunctim, quam divisim, voluit, et expresse consensit se, ac suos haeredes, et successores praedictos posse realiter, ac personaliter cogi, compelli, astringi, excommunicari, aggravari, reaggravari, et ad brachium seculare deponi, arrestari, capi, incarcerari, et detineri uno et eodem tempore, vel diversis temporibus, et per diversorum temporum intervalla usque ad plenariam, et integram praemissorum observationem, ac omnium et singulorum damnorum, expensarum, et interesse praemissorum occasione forsan faciendorum, et substinendorum integram refectionem, et restitutionem, ita tamen quod executio unius Curiae executionem alterius non impediat, nec retardet, non obstante iuris dispositione, quod ubi iudicium incęptum est, ibidem terminari debeat, et quod causarum continentiae non dividantur, et quod quis teneatur in ea actione, quam intentavit usque ad finem litis persisteret, et qualibet alia iuris, et facti exceptione in contrarium facente, non obstante, et quavis alia iuris, seu facti exceptione, quae posset alligari in contrarium facente, non obstante; ita quod una via electa non censeantur ullo modo alteri renunciatum. Insuper renunciavit omni et cuicunque exceptioni doli mali, vis, metus, fraudis, laesionis, et machinationis, non numeratae pecuniae, speique futurę receptionis, et numerationis praesentis contractus, non sic, ut praemittitur facti, celebrati, et initi, et aliter opus, vel minus suisque factum, vel dictum, quam recitatum, et e contra omnibusque aliis, et singulis exceptionibus, cavillationibus, et cautelis, quibus mediantibus contra praemissa, vel aliqua eorum d. A. debitor facere, dicere, venire, ac se tueri quoquomodo posset, et specialiter iure dicente generalem renunciationem, non valere, nisi praecesserit specialis, et expressa.

Renunciavit pariter idem A. debitori omni, et cuicumque appellationi, reclamationi, et recursui contra praemissa quomodolibet interponendis ac praesentis Instrumenti, et contentorum in eo vim, et effectum, ac executionem quomodocumque differentibus, retardantibus, seu impedientibus, nec non omnibus, et singulis legibus, et legum auxiliis, etiam quod essent speciali nota digna, quibus mediantibus se contra praemissa, vel eorum quolibet supra contenta et praemissa defendere, ac tueri, ac per quas praesentis Instrumenti vis, effectus, aut assecutio posset quomodolibet differri, vel retardari. Quinimo appellatione, reclamatione, et recursu huiusmodi, ut supra interponendis, ac introducendis, caeterisque omnibus exceptionibus non obstantibus hoc Instrumento, et omnia in eo contenta, in primis, et ante omnia debitum suum sortiatur effectum, ac debitae executioni penitus demandentur, ita et taliter quod appellatio huiusmodi, alięque exceptiones eidem A. quoad effectum suspensium minime suffragentur me Notaio tamquam publica, et autentica persona pro absentibus, ac omnibus, et singulis quorum interest, intererit, vel in futurum interesse poterit stipulante, et sic ad et super Sancta DEI Evangelia tactis scripturis in mei Notarii manibus sponte iuravit super quibus omnibus, et singulis praemissis peritum fuit a me Notaio unum, vel plura publica confici Instrumenta etc.

Notes

[1] For an in-depth study of the cameral obligation, its regulation and history, see Antonia Fiori, Espropriare e scomunicare. L’executio parata delle obbligazioni camerali (secoli XIV–XIX) (Naples, 2018).

[2] Romana seu Perusina census coram Brichio, 12 December 1644, dec. 162, no. 25, in Silvestro Zacchia, Lucubrationes ad Gallesium de obligatione Camerali, quibus praeter additiones eiusdem Authoris . . . accesserunt aliae Lanfranchi Zacchiae I.U.D. (Rome, 1647), p. 137.

[3] Le lettere di Michelangelo Buonarroti pubblicate coi ricordi ed i contratti artistici, ed. Gaetano Milanesi (Florence, 1875), p. 702.

[4] For the Saint Matthew cycle in the Contarelli Chapel, see Fabio Simonelli, “Le fonti archivistiche per la cappella Contarelli: Edizione dei documenti,” in La cappella Contarelli in San Luigi dei Francesi. Arte e committenza nella Roma di Caravaggio, ed. N. Gozzano and P. Tosini (Rome, 2005), pp. 117–154, at pp. 150–151 (doc. 17).

[5] For the Crucifixion of Saint Peter and the Conversion of Saint Paul in the Cerasi Chapel, see Luigi Spezzaferro and Almamaria Mignosi Tantillo, “Appendice documentaria,” in Caravaggio Carracci, Maderno. La Cappella Cerasi in Santa Maria del Popolo a Roma, ed. M. G. Bernardini et al. (Cinisello Balsamo, 2001), p. 110, no. 3.

[6] Sylvia Pressouyre, Nicolas Cordier. Recherches sur la sculpture à Rome autour de 1600, vol. 1 (Rome, 1984), pp. 256, 277–278.

[7] Raffaella Morselli, “Elogio dell’ingenium,” in Rubens e la cultura italiana: 1600–1608, ed. R. Morselli and C. Paolini (Rome, 2020), pp. 13–34, especially pp. 23–24.

[8] Stefania Tuzi, Il Palazzo della Sapienza: Storie e vicende costruttive dell’antica Università di Roma dalla fondazione all’intervento borrominiano (Rome, 2005), p. 96.

[9] Ordini dell’Academia de Pittori et Scultori di Roma (Rome, 1609), p. 31: Forma dell’obligo della Imprestanza. “Io N. confesso libero, & volontariamente hauer riceuto in pretito dall’Academia de’ Pittori & Scultori di Roma, per le mani di N. Offitiale di quella, la tal cosa, quale prometto fra termine di tanti giorni restituirla ben conditionata con obligo Camerale, da esequirsi con vna semplice Citatione, &c. Et in fede Io N. ho scritta, & sottoscritta la presente di mia propria mano, questo dì, & anno, in Roma.

Auuertendo, che in detta polizza, ò obligo, si disegni minutamente tutte le qualità della cosa imprestata, si è grande, ò picciola, se è nuoua, ò vecchia, se è sincera, ò ha qualche defetto, & di mano di chi sia. Auuertendo però, che non s’impresti cosa alcuna d’importanza à persona, che non habbia il modo, ò che non dia idonea sicurtà de riportarla in tempo promesso, ne tam poco a persona, che non gli si possa proceder contra, si non con buona sicurtà.”

[10] Ordini dell’Academia, p. 59: Forma della Polliza da farsi & sottoscriversi da quelli che vorranno le stime “Adi. 6 anno. &c. Io N. &c. hauendo per me N. & N. estimatori dell’opera N. stimata, &c. Prometto pagare infallibilmente per mia parte a ragione di due per cento, quel tanto, che mi toccherà della somma stimata, à li deputati dell’Academia, Congregatione, & Compagnia di San Luca, obligandomi non ricorrere per qual si voglia maniera, in qual si voglia modo a tribunale alcuno, eccetto, che al tribunale deputato da essa, et per essa Academia, Congregatione, & Compagnia di San Luca. Volendo, che possano detti Offitiali, in euento, che io non pagassi, con una semplice citatione venire alla essecutione del mandato reale, & personalmente fin che habbiano l’integra satisfactione di detta stima. Et in fede del vero Io N: di N. ho fatto la presente, & sottoscritta di ia mano il dì, & anno, &c.

Si procuri, che detta polliza sia stesa dal Notario dell’Academia, ò non potendo, sia sottoscritta da tre testimonij. & se parrà meglio, aggiungerui maggior cautela.” Even if the Statute does not state explicitly that the obligation is in forma Camerae, some of the elements indicated correspond to the stylus modernus of the obligation: the waiver to exceptions and appeals, submission to the jurisdiction of the tribunal appointed by the Accademia, the acceptance in case of nonfulfillment of execution against property and execution against freedom after a single summons. On the Statutes of 1607, published in 1609, see Isabella Salvagni, Da universitas ad Academia. La fondazione dell’Accademia di San Luca nella chiesa dei santi Luca e Martina. Le professioni artistiche a Roma: Istituzioni, sedi, società (1588–1705), vol. 2 (Rome, 2021), pp. 275–284.

[11] ASR, TNC, uff. 15, 1609, pt. 2, Vol. 45, 548r-v (1609/07/23)

https://www.nga.gov/accademia/en/documents/ASRTNCUff1516090723.html.

ASR, TNC, uff. 15, 1610, pt. 2, Vol. 48, 245r (1610/05/24)

https://www.nga.gov/accademia/en/documents/ASRTNCUff1516100524.html.

ASR, TNC, uff. 15, 1615, pt. 4, Vol. 66, 462r-v, 489r (1615/12/01)

https://www.nga.gov/accademia/en/documents/ASRTNCUff1516151201.html.

ASR, TNC, uff. 15, 1618, pt. 2, Vol. 76, 248r-v (1618/04/23)

https://www.nga.gov/accademia/en/documents/ASRTNCUff1516180423.html.

ASR, TNC, uff. 15, 1618, pt. 2, Vol. 76, 636r-v (1618/05/20)

https://www.nga.gov/accademia/en/documents/ASRTNCUff1516180520.html.

ASR, TNC, uff. 15, 1621, pt. 3, Vol. 89, 260r-v (1621/07/21)

https://www.nga.gov/accademia/en/documents/ASRTNCUff1516210721.html.

ASR, TNC, uff. 15, 1630, pt. 2, vol. 124, 859r-v, 874r (1630/06/14)

https://www.nga.gov/accademia/en/documents/ASRTNCUff1516300614.html.

ASR, TNC, uff. 15, 1630, pt. 3, vol. 125, 691r-v (1630/09/27)

https://www.nga.gov/accademia/en/documents/ASRTNCUff1516300927.html.

[12] ASR, TNC, uff. 15, 1609, pt. 2, vol. 45, 548v

https://www.nga.gov/accademia/en/documents/ASRTNCUff1516090730.html.

[13] ASR, TNC, uff. 11, 1607, pt. 2, Vol. 73, 976r-v, 985r (1607/05/27) https://www.nga.gov/accademia/en/documents/ASRTNCUff1116070527.html. On the inventory, see Salvagni 2021, pp. 276–278 and 508.

[14] ASR, TNC, uff. 15, 1621, pt. 2, Vol. 88, 808r-v, 837r-v (1621/06/10) https://www.nga.gov/accademia/en/documents/ASRTNCUff1516210610.html (“onde tutti li sudetti Sig.ri Confratelli rappresentanti tutto il Corpo della Congregatione Segreta riceverno et ricevono con ogni debita riverenza il sudetto breve promettendo et obligandosi di novo all’osservanza di esso et di detti Statuti et obligano anco tutto il corpo come officiali della Congregatione generale in forma Camera Apostolica et cosi giurano tactis etc. renunciando etc. consentendo etc.”)

[15] ASR, TNC, uff. 11, 1599, pt. 4, Vol. 44, 384r-v, 385r-v (1599/11/10) https://www.nga.gov/accademia/en/documents/ASRTNCUff1115991110.html.

[16] The Roman canonical ius commune was a legal system with a long tradition in continental Europe during the Middle Ages and the modern age. Despite the similarity of the name, it is not to be confused with common law, an Anglo-Saxon legal system.

[17] Guillaume Durand, Speculum iuris, pars II, partic. II, tit. de renunciatione et conclusione (Frankfurt, 1612), p. 403, no. 33.

[18] Nationis Gallicae in Concilio Constantiensi publica declaratio De annatis non solvendis, H. von der Hardt, Magnum Oecumenicum Constantiense Concilium de universali Ecclesiae reformatione, unione et fide (Frankfurt and Leipzig, 1700), tome VI, cols. 760–791.

[19] Fiori 2018, pp. 101–108.

[20] See, most recently, Andrea Cicerchia, Giuristi al servizio del papa. Il Tribunale dell’Auditor Camerae nella giustizia pontificia di età moderna (Vatican City, 2016); Fiori 2018, pp. 41–73.

[21] 22 December 1485, Bullarium Romanum, tome V (Turin 1860), no. 9, cols. 321–323.

[22] Bullarium sive collectio diversarum constitutionum multorum Pontificum a Gregorio Septimo usque ad S.D.N. Sixtum Quintum Pontificem opt. max. (Rome 1586), p. 170.

[23] Motu proprio Ministerio (1519), Bullarium sive collectio (Rome 1586), p. 238.

[24] Bullarium Romanum, tome VII (Turin 1862), p. 123.

[25] Bullarium romanu, tome VII (Turin 1862), p. 209.

[26] Cost. Sanctissimus, in Bullarium sive collectio diversarum constitutionum (Rome 1586), p. 98.

[27] Bullarium Romanum, tome VII (Turin 1862), p. 136.

[28] See note 24.

[29] Giovanni Battista De Luca, Theatrum veritatis et iustitiae (Venice, 1716), liber XV, p. I, disc. 7, p. 195, no. 44.

[30] Bullarium sive collectio diversarum constitutionum (Rome 1586), p. 949.

[31] Bullarium Romanum, tome VII (Turin 1862), p. 865.

[32] Bullarium Romanum, tome XII (Turin 1867), pp. 58–59.

[33] Fiori 2018, pp. 92–93.

[34] On the Congregazione del Buon Governo, see Gabriella Santoncini, Il Buon Governo. Organizzazione e legittimazione del rapporto fra sovrano e comunità nello Stato Pontificio, secc. XVI–XVIII (Milan, 2002); Stefano Tabacchi, Il buon governo. Le finanze locali nello Stato della Chiesa (secoli XVI–XVIII) (Rome, 2007).

[35] Sommario degl’aggravij che riceve il Tribunale di monsignor A.C. per gl’abusi e novità introdotte e che giornalmente s’introducono in pregiuditio di quello, e della sua giusrisditione, Archivio Storico Vaticano, Fondo Albani 15, 74r–79r.

[36] Laurie Nussdorfer, “Notaries and the Accademia di San Luca, 1590–1630,” in The Accademia Seminars: The Accademia di San Luca in Rome, c. 1590–1635, ed. P. M. Lukehart (Washington, DC, 2009), p. 60.

[37] The brief of Gregorio XIII, which can be read in Melchiorre Missirini, Memorie per servire alla storia della Romana Accademia di S. Luca (Rome, 1823), pp. 20–21, is reprinted in Lukehart 2009, pp. 348–349.

[38] ASR, TNC, uff. 11, 1606, pt. 3, vol. 70, fols. 340r-v, 351r (1606/07/31), https://www.nga.gov/accademia/en/documents/ASRTNCUff1116060731.html.

[39] As understood in legal parlance.

[40] In Europe, between the Middle Ages and the early modern age, other executive instruments besides the obligation in forma Camerae were provided with the so-called executio parata, that is with the prerogative of a particularly swift forced execution of the debt. The most famous of these instruments, because of its medieval origin and its diffusion, is the guarentigia. Every legal system of the Italian peninsula had its own particular executive pactum; if the guarentigia, mentioned by the medieval doctores, originated in Tuscany, Piedmont had the strumento sigillato, the Marche the instrument ad voluntatem, other regions the instrument confessionato, the Kingdom of Naples the obligation penes acta, and the Papal States the cameral obligation. Unlike other executive instruments used in various regions or states, the executio parata of the sworn, confessed, and guaranteed instruments were recognized on a broader level according to Roman canonical ius commune. On these subjects, see Antonio Pertile, Storia del diritto italiano dalla caduta dell’Impero romano alla codificazione, VI.2, in Storia della procedura, ed. P. Del Giudice (Bologna, 1966), pp. 127–128; Michele De Palo, Teoria del titolo esecutivo, vol. 1 (Naples, 1901), pp. 244–245; Francesco Schupfer, Il diritto delle obbligazioni in Italia nell’età del Risorgimento, vol. 1 (Turin, 1920); Dina Bizzarri, Il documento notarile guarentigiato (Turin, 1932); Enrico Besta, Le obbligazioni nella storia del diritto italiano (Padua, 1936), pp. 154–155; Adriana Campitelli, Precetto di guarentigia e formule di esecuzione parata nei documenti italiani del secolo XIII (Milan, 1970); Isidoro Soffietti, “L’esecutività dell’atto notarile. Esperienze,” in Hinc publica fides. Il notaio e l’amministrazione della giustizia, ed. V. Piergiovanni (Milan, 2006), pp. 163–183.

[41] “Primum, ac frequentius, magisque privilegiatum,” De Luca, Theatrum, liber XV, p. I, disc. 42, no. 24, p. 169.

[42] See note 40.

[43] For France in particular, see Véronique Beaulande, Le malheur d’être exclu? Excommunication, réconciliation et société à la fin du Moyen Âge (Paris, 2006); Tyler Lange, Excommunication for Debt in Late Medieval France: The Business of Salvation (New York, 2016).

[44] Adhémar Esmein, “Le serment promissoire dans le droit canonique,” Nouvelle revue historique de droit français et étranger 12 (1888): pp. 336–337; Paolo Prodi, Il sacramento del potere. Il giuramento politico nella storia costituzionale dell’Occidente (Bologna, 1992), pp. 320–321; Fiori 2018, pp. 109–121; Antonia Fiori, “Il giuramento come strumento di risoluzione dei conflitti tra medioevo ed età moderna,” Rivista Internazionale di Diritto Comune 28 (2017): pp. 141–157, esp. pp. 147–150.

[45] Gui Pape, Decisiones Grationopolitanae (Lyon, 1550), dec. 199, no. 3, fol. 132r.

[46] Harold J. Berman, Law and Revolution: The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition (Cambridge, MA, 1983), pp. 191–192.

[47] Josephus Zeliauskas, De excommunicatione vitiata apud glossatores (1140–1350) (Zurich, 1967), pp. 99–110; Stephan Kuttner, Kanonistische Schuldlehre von Gratian bis auf die Dekretalen Gregors IX (Vatican City, 1935), pp. 34–35; Elisabeth Vodola, Excommunication in the Middle Ages (Berkeley, 1986), p. 45.

[48] Sessio XXV de reformatione, cap. III, Sacrosancti et oecumenici Concilii Tridentini Paulo III, Julio III, et Pio IV, pontificibus maximis, celebrati canones et decreta (Paris, 1832), pp. 227–228.

[49] See note 31.

[50] On notaries, see, among others, Lorenzo Sinisi, Formulari e cultura giuridica notarile nell’Età Moderna. L’esperienza genovese (Milan, 1997); the essays collected in Hinc publica fides (Piergiovanni, 2006); Laurie Nussdorfer, Brokers of Public Trust: Notaries in Early Modern Rome (Baltimore, 2009); Maria Antonietta Quesada, “Notai degli uffici della Curia romana,” in Repertorio dei notari romani dal 1348 al 1927, dall’elenco di Achille Francois, ed. R. De Vizio (Rome, 2011), pp. xvii–xxiv.

[51] Sallustio Tiberi, De modis procedendi in causis, quae coram Auditorae Camerae aguntur. Practica iudiciaria (Rome, 1607), liber I, cap. 48, p. 113, no. 2.

[52] The cameral obligation had many elements in common with the guarentigia (on which, see note 39); for example, both were based on the confession of debt. Nonetheless, on the basis of the confession and with the consensus of the parties, in the guaranteed instrument the notary addressed the order to comply directly at the debtor by way of a praeceptum incorporated in the act. Formally this was made possible by an equalization of the confessio to the judgment, but it also entailed attributing the power of jurisdiction to the notary, which not all systems allowed. The Papal States did not recognize any formal delegation of jurisdiction to notaries. See Bizzarri 1932, p. 33; Giuseppe Salvioli, “Storia della procedura civile e criminale,” in Storia del diritto italiano, ed. P. Del Giudice, III.2 (Milan, 1927) (facsimile Frankfurt and Florence, 1969), pp. 658–664.

[53] Fiori 2018, pp. 135–139.

[54] On actuary notaries, see Lorenzo Sinisi, “Judicis Oculus. Il notaio di tribunale nella dottrina e nella prassi di diritto comune,” in Hinc publica fides (Piergiovanni, 2006), pp. 215–240.

[55] Tiberi, De modis procedendi, liber I, cap. 9, p. 11, no. 2.

[56] Tiberi, De modis procedendi, liber I, cap. 3, p. 6; Sigismondo Scaccia, Tractatus de appellationibus (Rome, 1612), liber III, cap. 2, quaestio 17, limitatio 9, p. 639, no. 5.

[57] Motu proprio Inter illa (see note 30): “ad executionem contra ipsum procedet, et in subsidium, ubi executio realis personalisve facile fieri non poterit, in ipsum tamquam contumacem contemptoremque sui praecepti, excommunicationem decernet. Haec tamen quoad excommunicationem monitio, ubicunque facilis futura esset executio, non adhibeatur.”

[58] On the legal treatises that describe the two styles of the cameral obligation, see Fiori 2018, pp. 28–39. For a more extensive description of the differences regarding the executive procedure, see Fiori 2018, pp. 135–176.

[59] Bullarium Romanum, tome XII (Turin 1867), p. 73.

[60] De Luca, Theatrum, liber XV, p. I, disc. 42, no. 24, p. 169, n. 24.

[61] See note 54.

[62] The decisions of the Roman Rota mentioned by the doctrine are numerous, beginning with the Aquilana pensionis coram Robusterio of November 7, 1576, cited by Tiberi, De modis procedendi, liber I, cap. 6, 9, no. 3. For all, I refer to the dec. 683, Decisiones Sacrae Rotae Romanae coram bon. mem. R.P.D. Matthaeo Buratto, vol. 2 (Lyon, 1660), pp. 338–339.

[63] De Luca, Theatrum, liber XV, p. I, disc. 42, p. 169, no. 24.

[64] Tiberi, De modis procedendi, liber I, cap. 44, p. 106, nos. 5–6.

[65] Tiberi, De modis procedendi, liber I, cap. 3, pp. 6–7, no. 6.

[66] Scaccia, Tractatus de appellationibus, liber III, cap. 2, quaestio. 17, limitatio 9, p. 639, no. 5.

[67] As understood in legal parlance.

[68] Pietro Ridolfini, De ordine procedendi in iudiciis in Romana Curia (Perugia, 1650), pars I, cap. 14, p. 240, no. 71.

[69] Giovanni Battista De Luca, Il Dottor Volgare, ovvero il compendio di tutta la legge civile, canonica, feudale e municipale, 4 vols. (Florence, 1843), liber XV, cap. 28, p. 275, no. 20.

[70] Antonio Massa, Ad formulam Cameralis obligationis liber (Rome, 1553), para. I, quaestio. 1, pp. 36–45.

[71] Giovanni Iacopo Bocca, De stylo curiae R.P.D. Auditoris Camerae libellus (Rome, 1561), fol. 39r–v.

[72] Massa 1553, Summa de processu ipso, p. 154, no. 3.

[73] Giuseppe Dall’Olio, Elementi delle leggi civili romane divisi in quattro libri, 2 vols. (Venice, 1825), liber III, tit. III, p. 25; [Antonio Pacini], Il notajo principiante istruito, vol. 1 (Perugia, 1774), p. 288; Antonio Rocchetti, Delle leggi romane abrogate, inusitate e corrette nello Stato pontificio e altre nazioni, vol. 3 (Fano, 1846), p. 20, no. 47.

[74] Zacchia 1647, p. 167.

Header image: Archivio di Stato di Roma, TCS, Vol. 0551, 1637, fol. 387v, detail