As you approach the Sonoran Desert in Arizona by car, saguaro cacti splay out on hillsides like stern, still palace guards. They herald the start of the desert, letting you pass but not without warning.

For those who spend time in the Sonoran, however, saguaros reveal something deeper. They are dynamic even as they remain rooted to the ground. They communicate with arm signals, embrace and dance with one another, whisper back and forth. Their girth expands and contracts with the availability of water, their ridges opening and closing like an accordion. Even their spiny exterior softens. The tops of their arms offer up white fuzz that signals new growth. In summer, they sprout large, white flowers.

For the Indigenous Tohono O’odham, the saguaro was traditionally the most important subsistence plant. It provided “food, drink, lumber, tools, and shade.” The people of Sonora, Mexico, used the word “saguarón”—big saguaro—to refer to tall, upstanding men.

But the Sonoran region has been changing over the past 150 years. Shaped by forces from colonialism to suburban sprawl, the desert is much different today. The forces affecting the region have transformed the saguaro as well. Images from the Sonoran document these changes—while also revealing each photographer’s distinct relationship to the desert and its tall guardians.

Timothy O’Sullivan’s Saguaro Sentinels

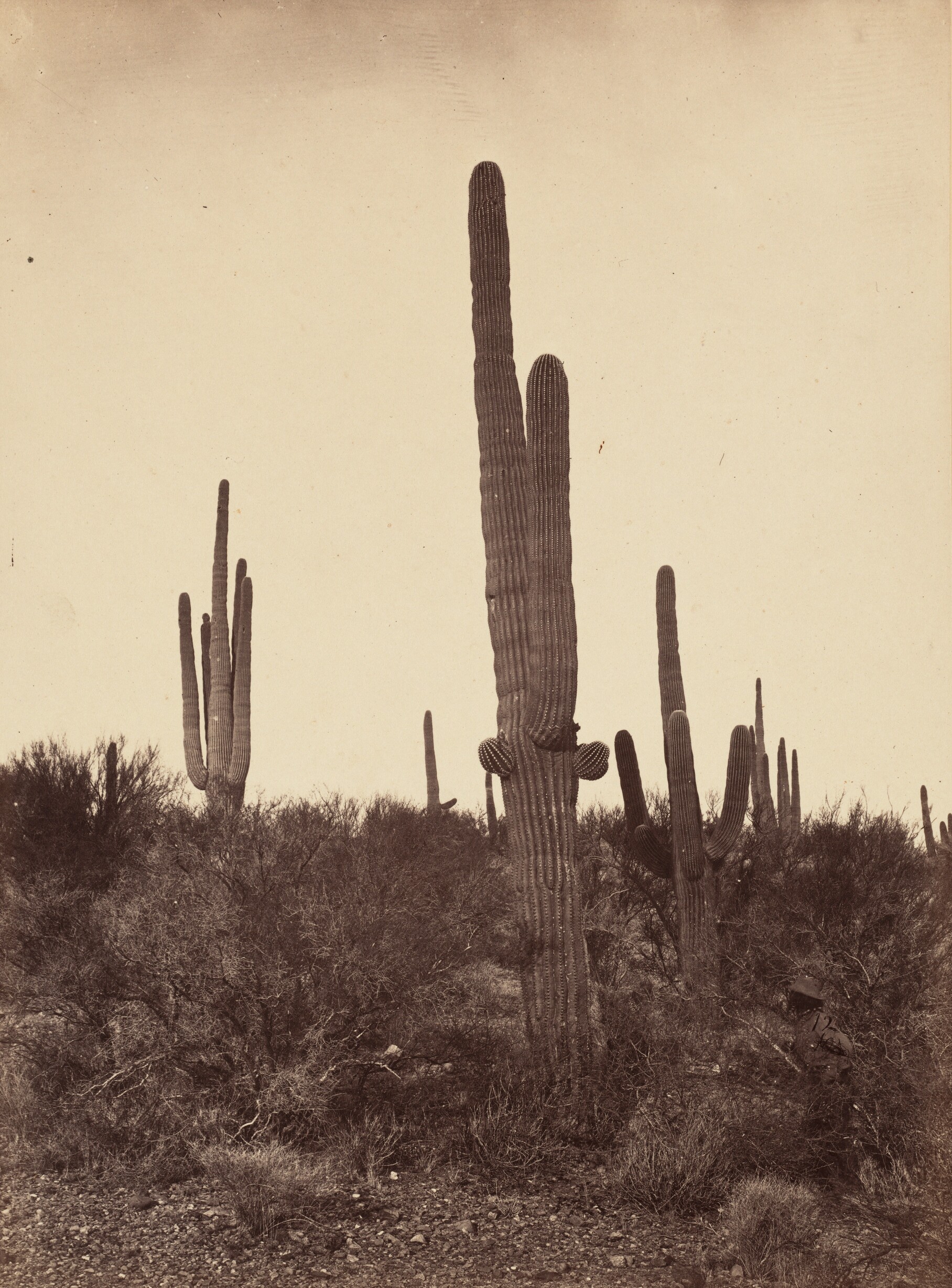

The saguaro cactus in the foreground of Timothy O’Sullivan’s 1871 Cereus Giganteus stands stock-still. Its main stem and single long arm reach up from the brush of the desert toward the cream-colored sky. Several round nubs point in the same direction, signals of future arms. Behind the main character, other saguaros also send their limbs skyward. Their towering forms and seemingly intentional spacing make them appear as proud guardians of the landscape.

Timothy H. O'Sullivan, Cereus Giganteus, Arizona, from O'Sullivan and William H. Bell's Geographical and Geological Explorations and Surveys West of the 100th Meridian, Seasons of 1871, 1872, and 1873, 1873, bound volume of albumen prints, Corcoran Collection (Gift of William Wilson Corcoran, 1886), 2014.136.381.1-50

O’Sullivan had been sent to the desert with a purpose. He was part of a team surveying the frontier lands that the United States government had acquired but knew little about. In 1871, 1873, and 1874, O’Sullivan worked on the Wheeler Survey. Its goal was to map the Western US and its mineral resources at a precise scale. Eventually, that information would help attract settlers. O’Sullivan was tasked with capturing images of the region.

Lee Friedlander Embraces the Saguaros

A hundred and twenty years after O’Sullivan, photographer Lee Friedlander spent enough time with saguaros for them to reveal their rich inner lives. In his 1993 photograph Arizona, Friedlander stands within the dense desert forest of the Sonoran Desert. It’s a type of landscape that only exists there—in the wettest desert in the world. O’Sullivan had captured it from far away, and the difference is powerful. The desert looks far more dense and vital from within.

In this photo, a long saguaro body curves gradually as it rises from a thicket of palo verde bushes. Its full height is cropped by the frame. Friedlander stands alongside the trunk, tilting his head to rest on the spiny ridge tops of the cactus. He holds the camera in his left hand, his arm stretched outside the frame like the saguaro. It looks as though he’s taking a selfie of them together. He wants to be seen alongside the saguaro; he wants to feel kinship with it.

Lee Friedlander, Arizona, 1993, gelatin silver print, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 2001.22.216

Lee Friedlander, Arizona, 1995, gelatin silver print, Patrons' Permanent Fund, 2001.22.232

Two years later in 1995, Friedlander made another Arizona in a similar Sonoran landscape. This time, the bramble surrounding the saguaro is a mess of mesquite branches. A mat of tree limbs and needles cover the bottom of the frame. A grassy plain is visible in the background through a gap on the left side of the image.

Instead of the tall, century-old cactus of the 1993 photo, here Friedlander poses with a saguaro that’s likely just a few decades old. It reaches the bottom of Friedlander’s chin; it has no arms. He positions himself three-quarters of the way behind it, letting the edge of his vest and pants show. His arms are outstretched, as though providing the plant’s future arms. The curvature of his head matches that of the saguaro’s head. He isn’t posing with the saguaro so much as becoming it.

Saguaros Displaced by Suburban Sprawl

O’Sullivan depicted the saguaros’ impressive command of the landscape. Friedlander portrayed their tenderness up close. Photographer Allen Dutton managed to capture both at once.

Dutton was born in 1922 in the Route 66 town of Kingman, Arizona. From the 1980s through the early 2000s, he photographed the sprawl of metropolitan Phoenix—and the saguaros it affected.

His work is reminiscent of that of Robert Adams and the new topographics. He depicts repetitive, cheaply constructed houses arranged around cul-de-sacs, newly built bridges, and traffic lights. With nothing but graded desert around them, retiree transplants pose alongside their palm trees and golf carts.

Allen Dutton, Maricopa County, Carefree Highway East of I-17, Looking Southeast to an Area to be Subdivided Within the Year, May 2000, gelatin silver print, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Brian and Lynda Lanker), 2016.22.140

Allen Dutton, Phoenix, I-17 and Carefree Highway, Prisoners of the Subdivision Wars, May 2000, gelatin silver print, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Brian and Lynda Lanker), 2016.22.142

After spending time with Friedlander’s photographs, saguaros may appear sentient and human. In Dutton’s work, they seem haunted by loss. In one photograph a line of saguaros stands between a background of mountains and a foreground of bushes and cholla cacti. Based on their short arms, the saguaros are likely around a century old. The May 2000 image could easily be mistaken for one from O’Sullivan’s survey. But the title gives it away as something else: Maricopa County, Carefree Highway East of I-17, Looking Southeast to an Area to be Subdivided Within the Year. These saguaros are not long for the world.

Or perhaps they will live a different, confined life. Another photograph from the same series is Phoenix, I-17 and Carefree Highway, Prisoners of the Subdivision Wars. It shows a dirt field cleared of natural vegetation and instead replanted with saguaros.

Presumably, they have been transplanted from soon-to-be subdivided tracts nearby. They wait to dot the lawns of the housing development to come. They are densely packed, without regard to their age or stature. Each has a ribbon around its stem. The largest and oldest are propped up with two-by-fours. They do seem like prisoners, held against their will.

Extreme Heat Threatens the Saguaro

For years, it appeared that sprawl was the key existential threat to the saguaros—and other beings—of the Sonoran. The new human inhabitants upset the desert’s complex water balance, drying up rivers and aquifers. But as the effects of human-caused climate change have intensified in recent decades, extreme heat has become another danger.

Summer 2023 was the hottest on record: Phoenix saw 133 days over 100 degrees. The stately saguaros began to collapse. Those most affected were the former prisoners—the ones that had been transplanted into suburban yards. They lack complete root systems and absorb the heat that radiates off the asphalt around them.

Experts say 2024 is shaping up to be even hotter. Instead of standing guard at the entrance to the desert, saguaros now greet visitors in distress. Those that have fallen are limp, slowly rotting down to their woody cores.

The desert has changed, and its sentinels have changed their countenance.

Caroline Eaton Tracey writes about the environment, migration, and the arts in the US Southwest, Mexico, and their borderlands.

Tracey’s reporting appears in the New Yorker, n+1, New York Review of Books, High Country News, and elsewhere, including in Spanish in Mexico's Nexos. She received the Waterston Prize for Desert Writing, Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Fellowship in Journalism and Human and Civil Rights, and a Silvers Foundation Work-in-Progress grant. Her first book, SALT LAKES, will be published by W. W. Norton.

Tracey holds a PhD in geography from the University of California, Berkeley.