Mark Klett is best known for rephotographing classic images of the American West. He, along with photo historian Ellen Manchester and photographer JoAnn Verburg, created the Second View project between 1977 and 1979, roughly a hundred years after the original (“first view”) photographs had been taken.

Today, people know those original pictures, made when the region was still being explored, indirectly. Many of them show what are now scenic overlooks in national parks. And the images are in major museum collections, including that of the National Gallery.

I first worked with Klett in 1998, when he was making his Third View project. It was about more than just rephotographs. Klett had brought a team of artists and their gear, including a video technician with sound recording equipment. The idea was to document the making of each image and post the results online every evening.

I was the writer of the group, charged with telling its story, but also with writing a book about Klett titled Viewfinder. Traveling with him through the West and its photographs, I was schooled in both space and time.

Finding the Original Vantage Point

Rephotography is the art of making a new photograph that replicates an old image. It involves finding the exact place from which the original image was taken—and the exact season and time of day.

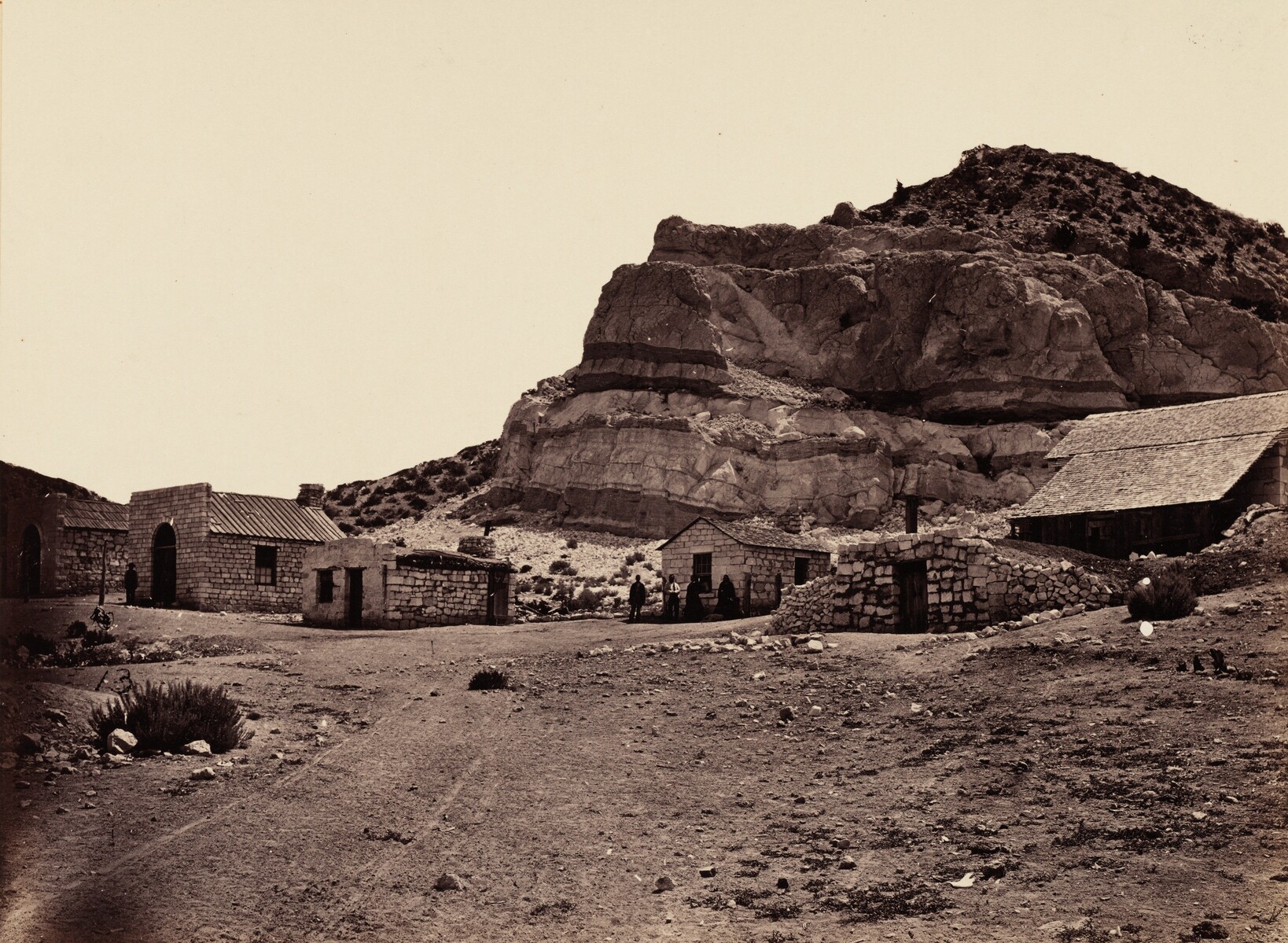

The first view I found with Klett was at the abandoned mining town of Logan in south central Nevada. Timothy O’Sullivan had photographed it in 1871. We drove east from Las Vegas, then north, almost reaching the tiny town of Hiko. It was dark when we found the dirt road proceeding west and up into the Mount Irish Range.

We entered Logan at midnight, driving right into what had been the middle of town. The sagebrush was thick all around us, and I was surprised when we simply stopped the trucks and camped in the middle of the road. When we woke, Klett got to work. I soon realized that finding the vantage point was as much art as science.

Timothy H. O'Sullivan, Water Rhyolites, Near Logan Springs, Nevada, from O'Sullivan and William H. Bell's Geographical and Geological Explorations and Surveys West of the 100th Meridian, Seasons of 1871, 1872, and 1873, 1873, bound volume of albumen prints, Corcoran Collection (Gift of William Wilson Corcoran, 1886), 2014.136.381.1-50

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Water rhyolites near Hiko, NV, for the series for Third View, 1998, silver gelatin photograph, courtesy of the artist

The vantage point is the site from which the first photo was taken, and finding it takes patience. First, the photographer lines up things in background of the original photograph with the scene in front of them. Using two points in the view, they “back triangulate” where to put the camera. Except the ground is always moving. There has been erosion or an earthquake. Or humans have built a road or a building where the original photographer stood. Or the view has changed. Out of the five structures in O’Sullivan’s image, only one house was still standing.

Klett would look at a print of the photograph, then duck under a black cloth covering his large-format camera. The image projected onto the camera’s glass back was upside down and in color. This created a disorienting space that wasn’t easy for me to match to the photo. I was used to looking into an eyepiece to see a framed view of the picture the camera would take, right side up.

Mark Klett, Under the Dark Cloth, Monument Valley, May 27, 1989, gelatin silver print, Gift of the Collectors Committee, 1996.102.1

Mark Klett and William Fox photographing in Arizona.

Finding the time of day requires studying the shadows to see where they point. The same is true for the time of year. Klett is so good at this that he can usually put his lens within a cubic foot of the original vantage point, within a day or two of the time of year, and within an hour of the time of day.

Traveling to the 19th Century through a Lens

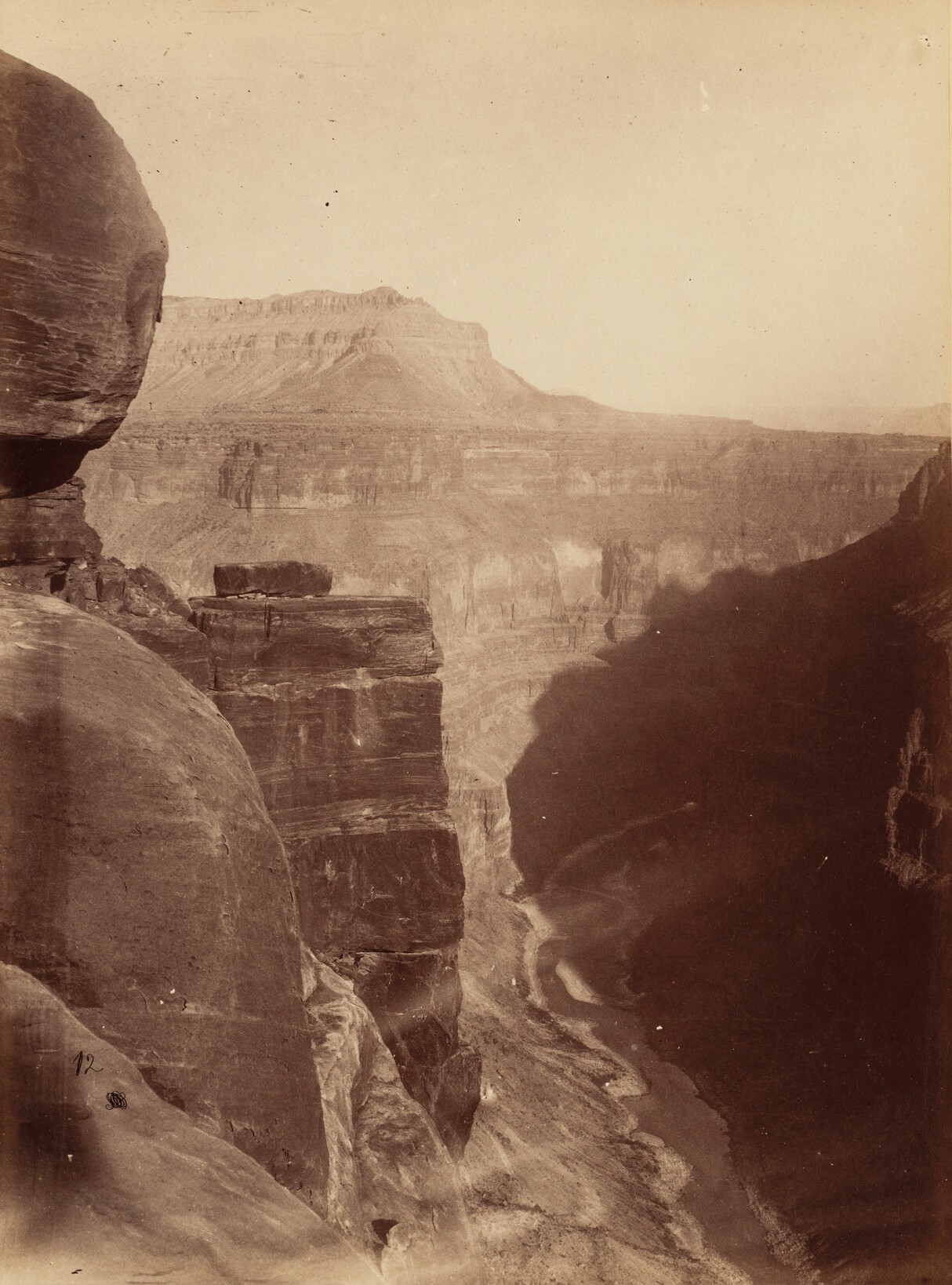

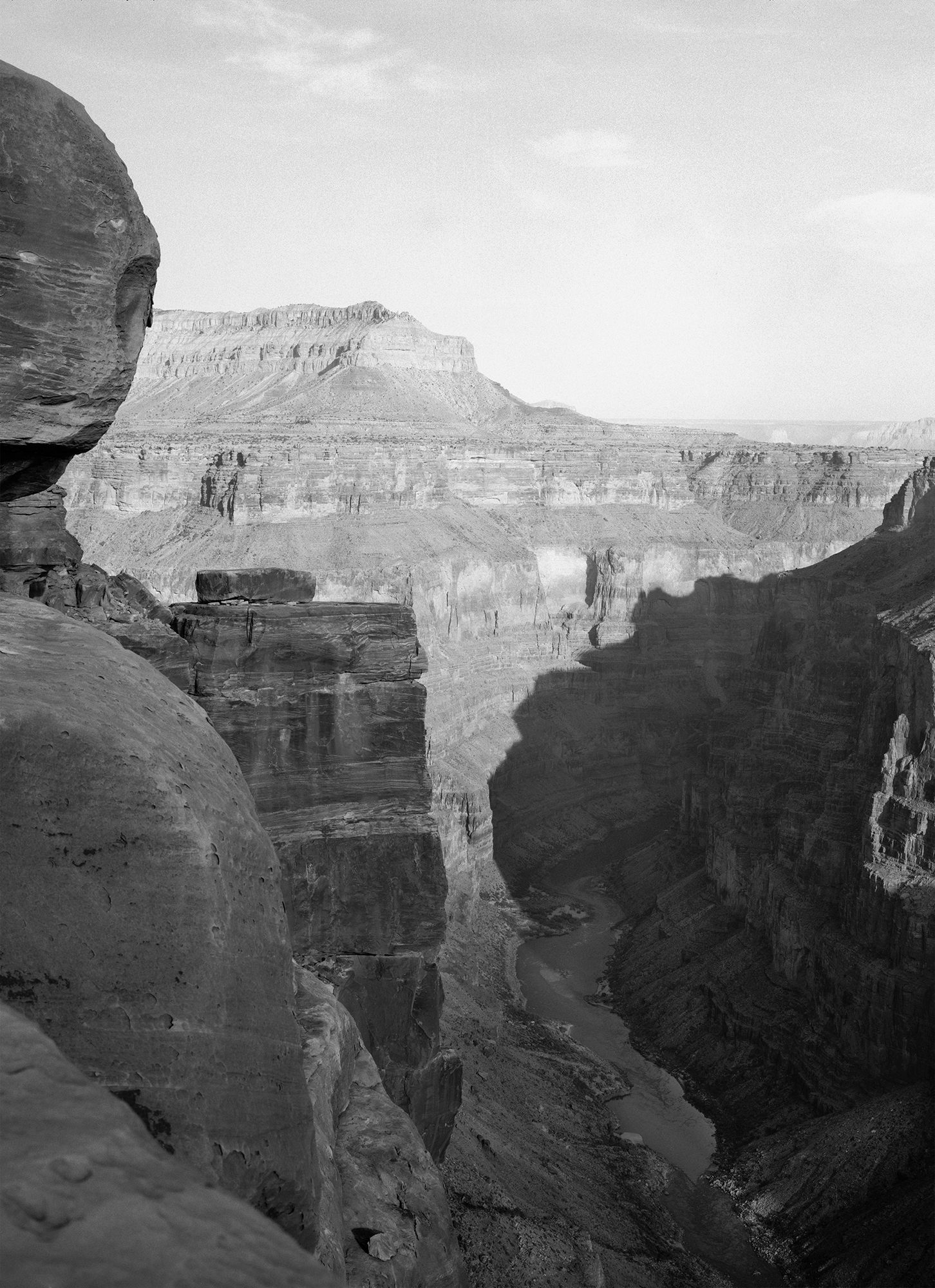

On another trip, Klett set out to recapture one of William Bell’s 1872 images of the Grand Canyon from its North Rim. But he and I had to question the photographer’s choice of vantage point. The sandstone ledge we found ourselves on was about 5,800 feet above the Colorado River. A single slip of only six inches would have sent camera and Klett over the edge.

I set up a belay (anchor point) for Klett attached to the cliff. His assistant Mike Marshall helped him load film and manage gear while I held the rope. I spent the next few hours watching the photographers, but also the condors circling overhead. One of the benefits of traveling with Klett for years has been the opportunity to spend time with seemingly every species of animal and plant in the American West.

William H. Bell, Grand Canyon of the Colorado River, Mouth of Kanab Wash, Looking East, from Bell and Timothy H. O'Sullivan's Geographical and Geological Explorations and Surveys West of the 100th Meridian, Seasons of 1871, 1872, and 1873, bound volume of albumen prints, 1873, bound volume of albumen prints, Corcoran Collection (Gift of William Wilson Corcoran, 1886), 2014.136.381.1-50

Mark Klett and Michael Marshall, Rock formations east of Toroweap, Grand Canyon National Park, AZ, part of the series Third View, 2000, silver gelatin photograph, courtesy of the artist

I also eventually developed the ability to read images in the field. I could see why O’Sullivan or William Bell or other exploration artists chose particular vantage points.

And at one point in central Nevada, I found myself atop a ladder in the bed of Klett’s pickup truck parked by the side of a dirt lot above town. I was looking at the glass under the cloth hood when I suddenly felt as if I were in the 19th century. I had left behind the present. In the cloud of the past, I faced the same set of possibilities that O’Sullivan had when he first framed this view.

Mark Klett & Byron Wolfe, From the Top of “Karnak Ridge” a columnar volcanic outcrop in central Nevada, for the Third View project, 1998, inkjet photograph, courtesy of the artist

Rephotography and Change over Time

The most memorable rephotographic day for me was in July 1998. We sat atop Karnak Ridge just southwest of Lovelock, Nevada. A small stretch of Interstate 80 was visible in the distance, as was part of the Forty Mile Desert. After a wet winter, it was completely flooded.

I’d first seen O’Sullivan’s photograph of the ridge in the October 1975 issue of Artforum. Seeing a hundred-year-old image of rural Nevada in the country’s leading avant-garde art magazine had floored me.

When we hiked to the ridge, I was surprised to find it only about 30 feet tall. I had assumed the columns of rhyolite (a volcanic rock) were hundreds of feet high. But O’Sullivan had tilted his camera to make the view more imposing.

Mark Klett and William Fox at work on their next project in Klett's Arizona studio.

In the 131 years between O’Sullivan’s photograph and our visit, the rocks around Karnak Ridge had shifted only a little. But if we waited a thousand years, it would look as though the ground had flowed downhill. And in a movie of the site that lasted 100,000 years, erosion would make the rocks look like a river.

Most people think change happens because of the passage of time. But Klett considers time as a manifestation of change, not the turning of hands on a clock. By inserting photographs taken more than 100 years ago into images from the current day, he deliberately weaves together past and present. This allows us to imagine the future.

This echoes how many Indigenous people around the world—from Australia’s desert Aboriginal people to the islanders in the Pacific Ocean—see time. Ancestral future, they sometimes call it. That future is embedded in the past, which is already present. It is humbling to see the technology of rephotography bring us to the same understanding.

William L. Fox is an art critic, artist, author, cultural geographer, editor, and poet. His writing is a sustained inquiry into how human cognition transforms land into landscape. His many nonfiction works rely on fieldwork with artists and scientists in extreme environments. He is director of the Center for Art + Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno.