In 1925, five years before Grant Wood painted American Gothic, an Omaha businessman commissioned him to create murals for the dining rooms of hotels in Cedar Rapids, Sioux City, and Council Bluffs, Iowa. It was the artist’s first major commission and a turning point in his aesthetic development. A century later, the Corn Room murals (and their afterlives) can help us understand how land, tradition, and personal experience have motivated rural, regional artists.

Grant Wood’s Vision of Modern Iowa

While Wood was born in Iowa, he did not engage much with rural subject matter until he made the Corn Rooms at age 34. He built his work from the foundation of his distinct lived experience. The artist spoke to reporters at the opening of the first Iowa Corn Room in Cedar Rapids’s Hotel Montrose in 1925. He described his “feeling for the culture and art in this section of the country, which is rapidly making it a place which New York artists look to with longing.”

Literary works from the region, such as Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio and Edgar Lee Masters’s Spoon River Anthology, had already made waves with a national audience. Beginning with the Corn Room murals, Wood’s work contributed a visual language to that movement. The first Iowa Corn Room featured a panoramic view of corn fields at harvest across four walls (a frieze). The lyrics to the “Iowa Corn Song” stretched across the top of the four walls. This further emphasized the resonance of those fields—as land, culture, and a productive economy.

New Road, a later work now in the National Gallery’s collection, captures the same bold visual language. The painting tells the story of road construction in the countryside around Cedar Rapids in 1939. Wood continues to accentuate slopes of land alongside the incursions of modern agriculture: cleared fields bisect the landscape. The painting is small, just 13 by 14 inches. In that modest space, Wood presents an expansive panorama that subtly shows social and ecological transformation to a rural landscape. In the coming years, World War II would accelerate those changes.

Grant Wood, New Road, 1939, oil on canvas on paperboard mounted on hardboard, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Irwin Strasburger, 1982.7.2

An Iowa landscape in 2023.

One historian estimates that more than 2,200 towns in Iowa had been abandoned by midcentury. Farmwork had become more mechanized, and farms consolidated, increasing in acreage. And the US population shifted dramatically from rural to urban areas, building new connections between these spaces. Today, migrant farmworkers make up more than 70 percent of the US agricultural workforce. The cultural moment of the regionalist movement has passed, and regional experiences have become more diverse and expansive.

Contemporary Artists Reflect on Iowa’s Evolution

For the last 15 years, I have seen these changes up close as the executive director of Art of the Rural. Our nonprofit organization provides artists and culture bearers across the country the resources to build the field, change narratives, and bridge divides. I have experienced how often the urban is assumed to be the default. This masks the dynamic racial, social, and economic change happening across the rural United States and Indian country. The national conversation often imposes a binary of nostalgia and crisis on these communities. But their visions are far more complex. And the diverse work of contemporary artists reflects their energies.

Timothy Wehrle, Inner Kingdom Thieving Speedway, 2009, watercolor on paper, Des Moines Art Center, 2009.71

Laurel Nakadate, Pikeville, Kentucky #1, 2013, from the Relations series, Type-C print, 30 x 45 inches, © Laurel Nakadate, Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects

Working in a small town not far from the intersection in New Road, self-taught artist Timothy Wehrle examines the region with vivid, kaleidoscopic vision. His 2009 work Inner Kingdom Thieving Speedway uses watercolor, graphite, and colored pencil to suggest mobility and claustrophobia. Both come with living in a small town where the economic and cultural decline is tied to the nonstop currents of nearby Interstate 80. The work is an elaborate critique of Iowa’s monoculture (the cultivation and growth of a single crop)—both agricultural and social. Wehrle casts local history through the prism of dreams, metaphors, and allusions. The power in his hypnotic, mirroring work comes from the meeting of interior and exterior worlds.

Laurel Nakadate’s work appeared alongside Wehrle’s in the Des Moines Art Center’s recent exhibition Art Center: 75 Years of Iowa Art. Nakadate, whose lineage is Japanese American, now lives in New York City, but was raised in Ames, Iowa. In her Relations series, she used DNA testing to find family members—and uncovered ties to the descendants of both enslaved people and Mayflower passengers. She then took a years-long journey across 31 states to meet and photograph distant cousins. Nakadate’s creative genealogical research reveals the complex, intermingled families that run alongside the history of the United States, connecting rural and urban spaces.

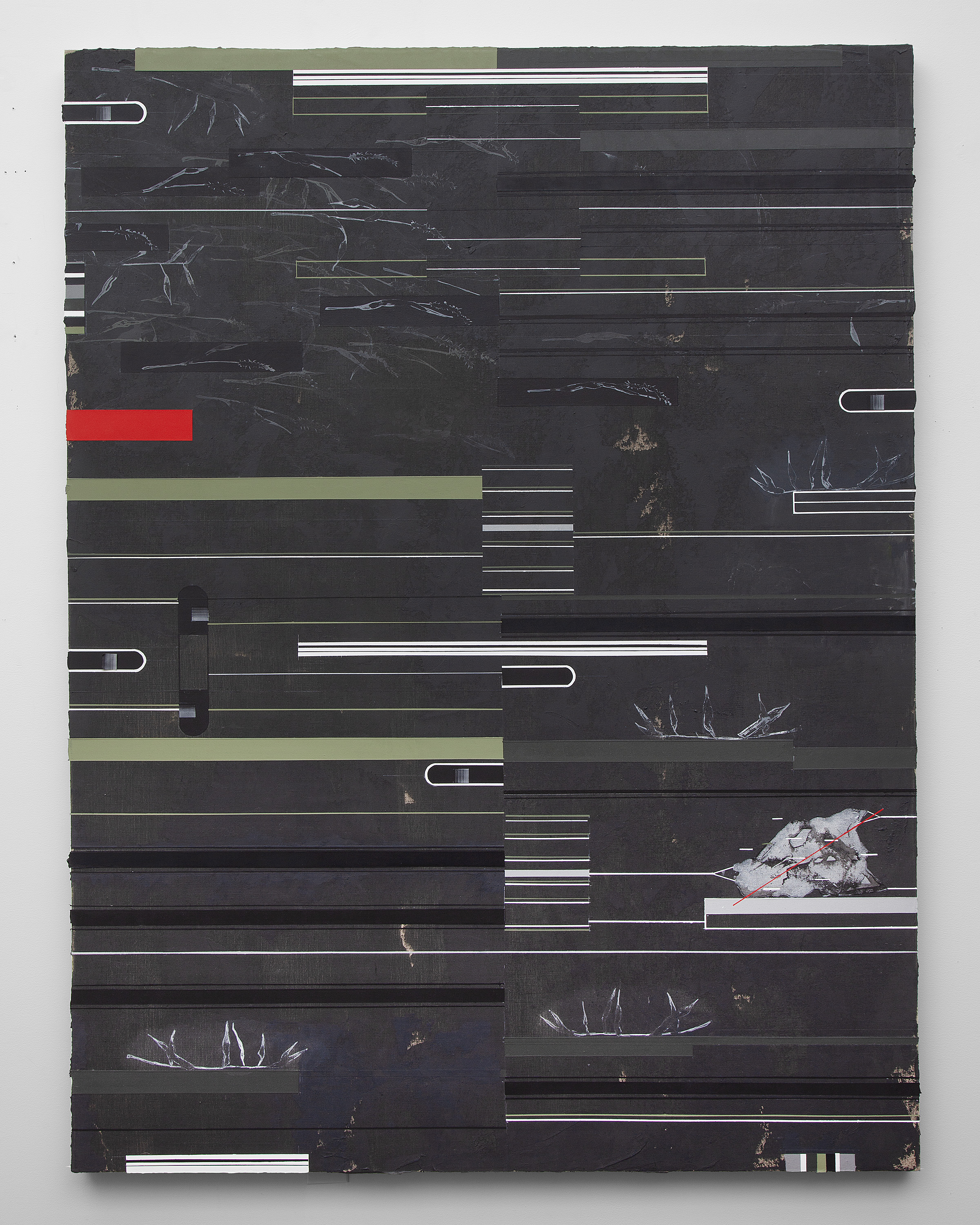

Duane Slick ( Meskwaki/Ho-Chunk), Midnight in the Metaphysical Economy, 2021, The John and Susan Horseman Collection, Courtesy of the Horseman Foundation

The crossroads of lineage and land are also central to the paintings and video installations of Duane Slick. Slick is a citizen of the Meskwaki (Fox of Iowa) and Ho-Chunk (Nebraska) nations, and his work honors his peoples’ lived experiences and belief systems. His art underscores and complicates the ways in which Indigenous knowledge is appropriated. In his 2021 painting Midnight in the Metaphysical Economy, Slick depicts grasslands. They evoke so much at once: a field swaying in the wind, the trickster figure of the coyote, the modernist color field. Most directly, they reference the lands of the Meskwaki Nation—“people of the red earth.” This land, frequently represented in the popular imagination by Grant Wood, is Native land. Stereotypes and cultural shorthands for rural places often erase their spiritual, relational presence.

The Corn Rooms Today

In the lean postwar era, the Iowa hotels hosting Wood’s Corn Room murals fell on hard times. Over years of vacancy and eventual new ownership, the murals gathered dust, were wallpapered over, or were removed in pieces as souvenirs. Recent efforts by local arts organizations in Council Bluffs and Sioux City have successfully salvaged them in pieces.

Brought out of their original contexts into the light of new galleries, the reconstructed Corn Rooms now challenge the meanings we conventionally apply to Wood’s work. They even resist the original intent behind their creation. In Sioux City, removing wallpaper from the mural’s surface also stripped the upper layers of painted detail from the landscape. This left outlines of farm buildings and a hazy horizon, with bold corn stalks in the foreground. Curators believe that Wood likely applied this first layer of paint with his fingers. These fragments both mark the social and cultural changes that have shaped the region and are now marked by them.

The Sioux City Art Center has created a permanent, immersive exhibition of the reconstructed Corn Rooms. Placed in conversation with contemporary galleries, they give us a window onto an agricultural and settler past. And they help us imagine futures that combine the region’s diverse experiences of land, culture, and knowledge.

Artists have always made, and remade, images to represent their cultures. They invite us all to sit for a moment with those deep complexities and connections. From that space, we can tell a truer story about the places we are from.

Matthew Fluharty is

a writer and curator whose work meditates on land, cultures, and

communities. He is the Executive Director of Art of the Rural, a member

of M12 Studio, and an Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

Curatorial Fellow. He is a priest in the Zen Garland Order and currently

lives in Winona, Minnesota, a town located within Dakota homelands

along the Mississippi River.

Banner image: An installation view of Grant Wood's Corn Room (1926) at the Sioux City Art Center, Permanent Collection, 2007.17, Gift of Alan Fredregill