Dutch artist Judith Leyster was just 20 years old when she painted this virtuosic self-portrait in 1630.

But Leyster went missing from the art historical record for centuries. Her paintings were misattributed to male artists. Only in the past 100 years has she been recognized as a leading light of the Dutch Republic.

Today, her self-portrait is one of the National Gallery’s most popular paintings. In it, we see her expressive brushwork and her talent for capturing a lively manner. There’s no better introduction to Leyster than her own self representation. Get to know one of the rare women painters of the 17th century.

Judith Leyster, Self-Portrait, c. 1630, oil on canvas, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, 1949.6.1

A lively manner captured on canvas

-

What might Leyster have been trying to tell us about herself?

/

-

Her open and inviting expression immediately draws us in.

/

-

She leans back against her chair, propping her arm on it, apparently pausing her work to chat with us.

/

-

Her lips are parted, as if she is speaking. “Step into my studio,” she seems to say. “I’ll be with you in just a minute.”

/

Dutch art patrons prized that fresh quality—the sense that they were encountering sitters in real life, not in a formal, stiff pose.

See, for example, this portrait by Leyster’s contemporary Frans Hals. His sitter Willem Coymans looks similarly casual.

Frans Hals, Willem Coymans, 1645, oil on canvas, Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.69

While Leyster was capturing that attitude, she was also doing something unusual. Men were often painted in this kind of active, assertive pose. It was rarely seen in portraits of women.

But what looks relaxed to us required an incredible amount of skill and effort. Take a seat, and try looking over your shoulder. How long can you hold that position?

Leyster would have had to return to this pose again and again for reference. Looking this relaxed is a lot of work.

A lavish costume for a successful artist

-

Your eyes might stop on the dramatic, stiff collar around Leyster’s neck.

/

-

It’s extravagant in its diameter, pure white, trimmed with expensive lace.

/

-

This fashion was all the rage in the 17th-century Dutch Republic.

/

-

But wearing such a collar while working would have been utterly impractical for a painter. (Notice how it would prevent her from getting close to her canvas).

/

-

Observe the position of the collar.

/

-

It echoes the shape and tilt of the paint palette in the artist’s hand.

/

-

Leyster’s expensive collar, headpiece, and silk dress advertise her success. We are meant to trust the skills of an artist who can afford to dress so finely.

/

-

They may also reflect the tradition of the “gentleman artist”—or the gentlewoman, in this case.

/

-

Artists had long been considered artisans, performing a sort of messy manual labor. Showing themselves in elegant clothing helped elevate painting as an intellectual pursuit.

/

A painting within the painting

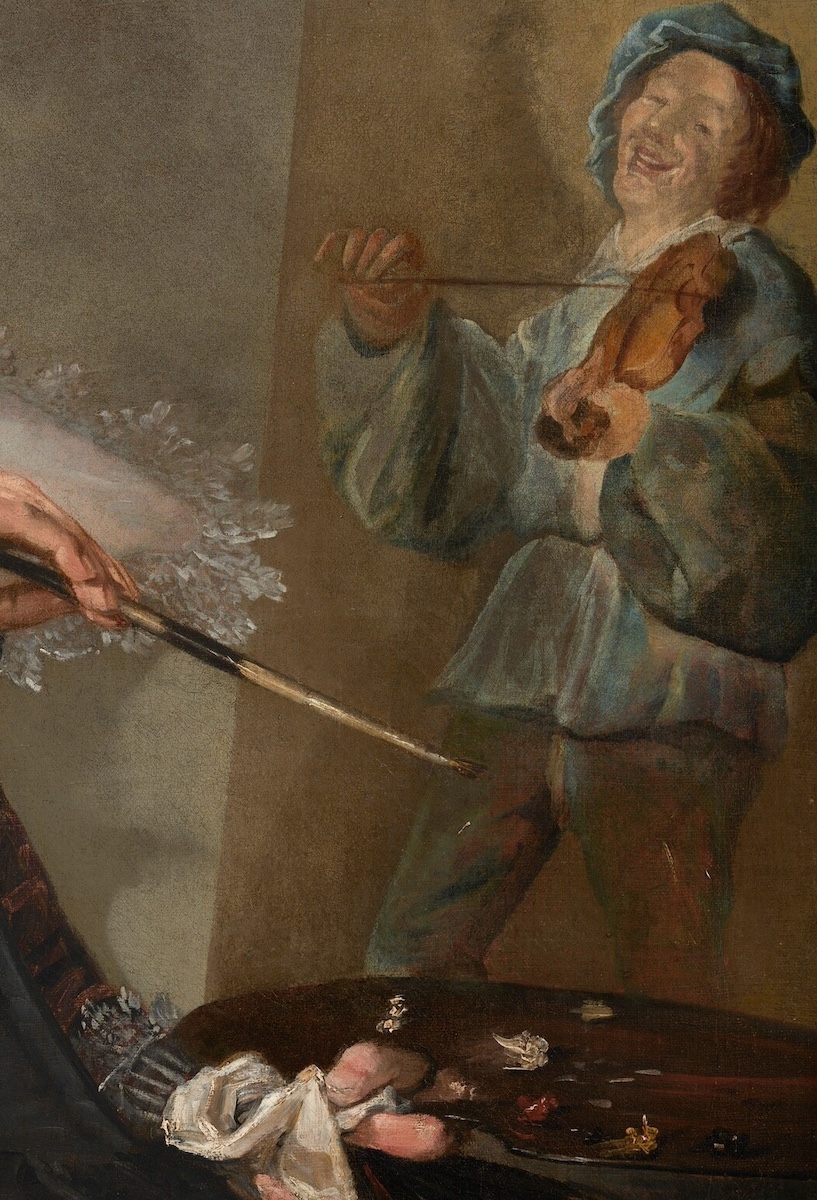

Leyster is in the middle of painting a spirited violin player. This musician is from a larger work called Merry Company, which she had completed the year before in 1629.

Judith Leyster, detail of Self-Portrait, c. 1630, oil on canvas, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, 1949.6.1.

Judith Leyster, Merry Company, c. 1629. Oil on canvas. The Klesch Collection.

Here, the violin player advertises the kind of paintings you could buy from Leyster. She specialized in “merry companies,” a genre that depicted scenes of mirth, often with music, drinking, and dancing. It developed in Haarlem in the early 1600s and remained popular throughout the century.

Thanks to infrared reflectography scans, we can see the underpainting. Leyster originally painted the face of a woman. It was likely of the artist herself, a self-portrait within a self-portrait. She probably switched to the violinist due to the success of Merry Company.

A leading star of her time

How was Judith Leyster received in her time? By all accounts, she achieved great success—as an artist in her own right and especially as a woman working in a mostly male industry.

Haarlem city chronicler Theodore Shrevel wrote in 1648,

There also have been many experienced women in the field of painting who are still renowned in our time, and who could compete with men. Among them, one excels exceptionally, Judith Leyster, called “the true Leading star in art.”

Shrevel’s praise includes a play on Leyster’s surname, which means “lodestar” or “leading star.” She often used the initials J and L crossed by a star to sign her paintings.

In the Dutch Republic, as in the rest of Europe, professional women painters were rarer than Shrevel suggests. Leyster was one of the only two women accepted as a master to the prestigious Haarlem painters’ guild in the entire 17th century. By 1635, she had taken on three pupils, a sign that she was a renowned artist.

Leyster disappears from view

But only six years after finishing this self-portrait, Leyster fell out of view for centuries. In 1636 she married painter Jan Miense Molenaer. (You can see him as a lute player in this self-portrait.) Few paintings by Leyster can be dated after her marriage. She managed Molenaer’s business affairs, may have helped with his paintings, and raised their five children.

Jan Miense Molenaer, Self-Portrait as a Lute Player, c. 1637/1638, oil on panel, The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund, 2015.20.1

For more than 200 years, Leyster remained largely forgotten.

Her better-known contemporary Frans Hals came back into vogue in the 19th and 20th centuries. Knowingly or not, dishonest dealers made a fortune passing off Leyster’s works as Hals’s. It was only in 1897 that Merry Company was authenticated as Leyster’s work—and a rediscovery of her other works ensued.

Today, about 35 works are attributed to her.

A missing portrait rediscovered

In 2016 another Leyster self-portrait was found at an English country estate. Made about 20 years after the one in our collection, this long-lost treasure had been hanging in the house for centuries. Its owners had no idea who it was of or by.

“I have been looking for this picture my whole life,” said art historian Frima Fox Hofrichter. She had seen a record of “an oval portrait of the wife of the deceased” in the inventory of Molenaer’s possessions after his death.

The fact that the portrait had remained with Leyster’s family suggests that it was an intimate work. Leyster had not painted it not for sale.

Judith Leyster, Self-Portrait, c. 1630, oil on canvas, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, 1949.6.1

Judith Leyster, Portrait of the artist, c. 1650, oil on panel, 12 1/8 x 8 5/8 in. Private collection, courtesy of Christie's.

In the earlier portrait, we see Leyster in her youth, brilliant and inviting. In the later one, a more reserved Leyster looks back at us with a steely gaze. But her talent remains intact. She still renders the deep flush of her cheeks and the delicate, translucent lace trimming her garments.

And she still portrays herself as a painter, palette and brush in hand.