It was the picture event of the year. The press had been teasing the release for months. Thousands lined up to buy their tickets to see the newest creation of an American visionary.

In 1857 Frederic Edwin Church revealed his seven-foot-wide painting Niagara. The one-picture exhibition was a sensation, cementing Church as the most important American artist of his day. Long before box office hits or record-breaking art shows, Niagara’s exhibition became the blockbuster of its day, changing the nation’s art and culture in the process.

The Critic’s Challenge

Church had established himself as a painter with a reputation independent of his teacher, Thomas Cole. The 30-year-old had recently gotten praise for his scenes of South America. Church painted the luminous The Andes of Ecuador in 1855. More than six feet wide, it was the largest work he had yet made. Critics and the public were transfixed. They called it “striking and bewildering.”

But not all the canvases he created based on his trip south were received as well. Tequendama Falls, near Bogotá, New Granada was Church’s attempt to reproduce what he called a “terrific” chasm and series of waterfalls. Despite the artist’s careful study of the natural wonder, not everyone felt that he had successfully captured it. One critic wrote that Church “should not paint falling water—for he cannot.”

Unafraid of a challenge, Church decided to paint North America’s most spectacular falling water—Niagara Falls.

Frederic Edwin Church, Niagara, 1857, oil on canvas, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund), 2014.79.10

A New Niagara

Unlike his Latin American landscapes, Niagara was not new to American audiences. The set of waterfalls on the United States-Canada border was already a popular tourist and honeymoon destination.

Images of the falls were everywhere in the 19th century. Countless prints and early photographs reproduced the wonder. It had become a national symbol.

But few, if any, artists had managed to truly render the falls. “Niagara was considered almost unpaintable,” says Franklin Kelly, a Senior Curator and Christiane Ellis Valone Curator of American Paintings at the National Gallery. “No one seemed to get it.”

Perhaps knowing the potential to amaze the public if he succeeded, Church set out to paint Niagara. He sketched the site during a series of up to five visits in 1856. The artist moved around the landscape, making sketches from different vantage points on both the Canadian and American sides.

Back in his New York studio, Church puzzled all these perspectives together and landed on a view across the Horseshoe Falls from the Canadian side. Oil sketches showed him beginning to play with perspective. Removing any foreground and expanding the view of the falling water, Church found a composition that translated the grandeur of the falls.

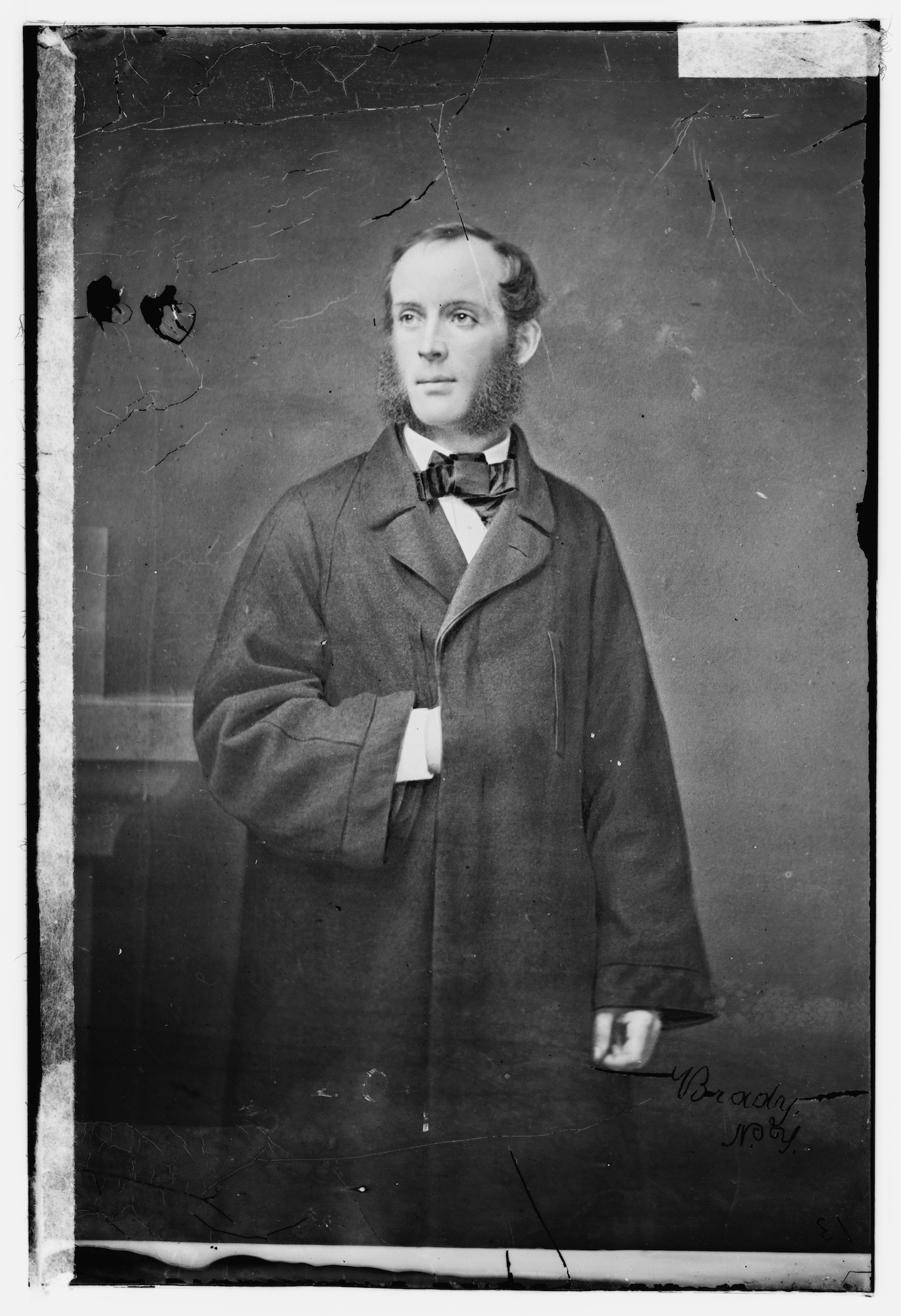

A photo by Mathew Brady of Frederic Edwin Church, taken between 1855 and 1865, around the time he made Niagara.

Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

The Master Marketer

Church clearly felt he was onto something great. Even before he had begun the final painting, the artist started to build anticipation for it. He invited writers to his studio to report on his work in progress.

Media was booming in New York City—the city alone had three daily papers. And just as the tabloids of today track casting announcements and filming locations for movies, newspapers and art journals followed the every move of famous American artists, previewing the next big thing.

Meanwhile, business models for artists had changed. “A major shift was occurring in the 19th century in this country, away from aristocratic patronage of the very rich,” Kelly explains. Artists did not have to rely on individual patrons to commission or buy their works.

The growth of the middle class created a new group of art admirers. Collectors and critics no longer determined the measure of an artist. The public now had a say, too. Church was “painting to a different, much broader audience,” says Kelly.

And since institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art didn’t exist yet, group exhibitions like the annual one at the National Academy of Art and Design provided a rare opportunity to see artists’ newest creations.

A visitor takes in Frederic Edwin Church's Niagara in West Building Gallery 71.

Niagara’s Spectacular Debut

Together with his gallery, Williams, Stevens, & Williams, Church decided to present Niagara in a dramatic single-work exhibition. He felt that the painting could be better appreciated on its own, outside of crowded group exhibitions.

Probably seeing the profit potential, Williams, Stevens, & Williams bought the painting and copyright for $4,500. The gallery set admission at 25 cents (around $9 today). Visitors received a pamphlet with details on ordering a chromolithograph (multicolor print) of the work.

On May 1, 1857, the doors opened. The public streamed in. Over the next three weeks, tens of thousands visitors came to take in the painting. Some brought binoculars or handheld telescopes to get a better look.

Critics were equally blown away by Niagara. Where others had failed, Church had succeeded in capturing the site’s magnitude and beauty. “This is Niagara, with the roar left out!” wrote one critic. “The finest oil picture ever painted on this side of the Atlantic,” said another.

Church’s risky endeavor had paid off.

Niagara on Tour

After the exhibition in New York, Niagara was shown in London, England. American media proudly shared news of the painting’s journey across the Atlantic. Another tour around the United Kingdom followed in 1858 with stops in London, Glasgow, Manchester, and Liverpool. Crowds were eager to see the painting that had made a splash across the pond.

The most important visitor to the London exhibition (at least for Church) was art critic and writer John Ruskin. His ideas about nature and art had been hugely influential to Church’s artistic practice. Getting Ruskin’s approval of Niagara was the ultimate test. And Church excelled. As Kelly tells it, Ruskin “supposedly walked up to it, saw the rainbow, and waved his hand to see if it was light being refracted through the window.”

The painting returned to New York City in fall 1858 a star. “The reputation of this work has greatly increased by its English tour. It is now regarded as the finest painting ever executed by an American artist,” wrote one critic. A second presentation at Williams, Stevens & Williams gave those who had missed out a second chance to be part of the sensation. Classified ads alerted readers to the exhibition—and then of its final days.

Like the stadium concert tours of today, the painting’s tour continued around the United States, stopping in Baltimore, Maryland; Washington, DC; Richmond, Virginia; New Orleans, Louisiana; Boston, Massachusetts; and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In each city, newspapers advised locals to take advantage of the special opportunity to see Niagara.

Eventually collector John Taylor Johnson bought the painting. He lent the work to the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867, where it was awarded a silver medal. In 1876, Johnson sold Niagara to the Corcoran Gallery of Art for $12,500 (the equivalent of more than $257,000 today).

A recreation of the original frame Church conceived for The Heart of the Andes.

Frederic Edwin Church, The Heart of the Andes, 1859, oil on canvas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Contemporary Parallels

Soon after the success of Niagara, Church moved on to his next painting. The artist was now expected to create major landscapes that would dazzle and challenge audiences.

Church set off for South America in pursuit of a striking new landscape. The result was The Heart of the Andes. For its debut in 1859, Church upped the drama, commissioning an enormous frame to enhance the perspective in the picture. To inspect all the painting’s remarkable details, visitors to the exhibition received opera glasses.

Thousands flocked to see Church’s newest work. On the final day of its exhibition, visitors waited in line for hours. The artist had made another hit.

While Church wasn’t the first to create special exhibitions, his skills at both painting and publicity raised their profile as never before. They feel like the 19th-century parallel to contemporary art sensations like Marina Abramović’s performance of The Artist Is Present at the Museum of Modern Art. Or the continued public obsession with Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms. Just as social media has made these works into cultural spectacles, the media of the 1860s lifted Church’s paintings to a new level.