In the early 1930s, Alfred Stieglitz again made New York City a subject of his work. His final gallery, An American Place, which he opened soon after the stock market crash of 1929, overlooked the city from the seventeenth floor of a new Madison Avenue office building. From those windows (Key Set number 1377), and from those of his thirtieth-floor apartment at the nearby Shelton Hotel (Key Set number 1391), Stieglitz recorded the frenzied building boom that transformed New York in the Great Depression.

Once settled on a particular view, Stieglitz made several variations at different times of day over the course of weeks or months, registering the growth of the buildings, the changing light and shadows, and the passage of time. Mostly shot head-on with his large, 8 × 10-inch view camera, Stieglitz’s rigorous compositions, rendered as crystalline gelatin silver prints, bespeak order and clarity. But for all of their formal beauty, they also represent the city as cold and inhuman—as Stieglitz made plain when he exhibited them in 1932 together with his earlier, more hopeful views of New York.

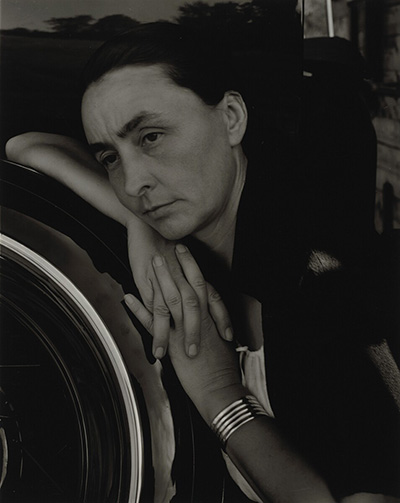

The early 1930s marked a rocky period in the Stieglitz–O’Keeffe relationship. Georgia O’Keeffe became increasingly independent, spending summers in New Mexico starting in 1929. Stieglitz began an affair with a much younger woman, Dorothy Norman. Stieglitz depicts O’Keeffe with symbols of her independence, such as her southwestern blankets (Key Set number 1437) and animal bones (Key Set number 1432), or the new car she had just bought (Key Set number 1516). Strong formal studies, they speak to the chill between them. At the same time, as O’Keeffe knew, Stieglitz was eagerly making photographs of Dorothy Norman (Key Set number 1367).

Alfred Stieglitz, Poplars—Lake George, 1935, gelatin silver print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.750

Key Set number 1575

Frequently alone at Lake George, Stieglitz, who turned seventy in 1934, started making quiet, autobiographical works based on his surroundings. A photograph of the small wooden building O’Keeffe used as her studio, with a dead tree branch extending across the doorway, evokes her absence (Key Set number 1557). Stieglitz also made photographs of nature in which he tried to bring the visual clarity that he imposed on New York City to the rural landscape (Key Set number 1508). Most poignantly, for much of the decade Stieglitz made a series of studies recording dying poplar trees, which he saw as emblems of himself (Key Set number 1575).

Ill health forced Stieglitz to put down his camera for good in 1937. He died in 1946.