Stieglitz’s Portfolios and Other Published Photographs

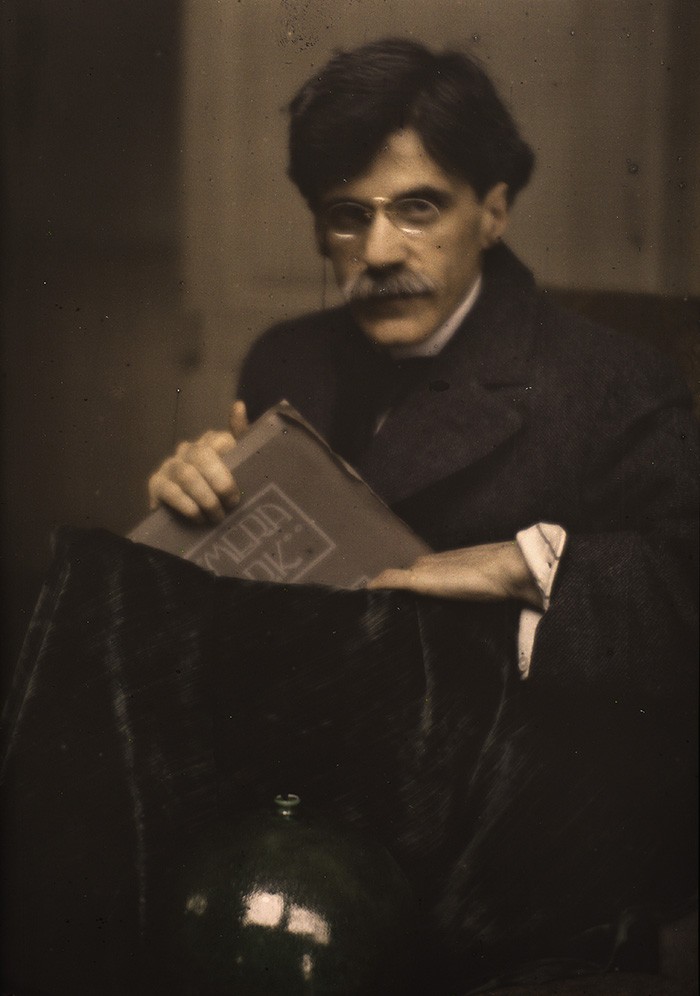

Edward J. Steichen, Alfred Stieglitz, 1907, Autochrome, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1955 (55.635.10). © 2019 The Estate of Edward Steichen / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

Alfred Stieglitz has been celebrated as one of the greatest practitioners of the photogravure process, but his understanding and exploration of other photomechanical printing methods is less well known. While a mechanical engineering student at the Königliche Technische Hochschule, Berlin, in the mid-1880s, Stieglitz was introduced to photogravure and photomechanical processes by the renowned photo-chemist Professor Hermann Wilhelm Vogel (1834–1898), who convinced him that photography would be useful to his field of study. Stieglitz later recalled that, while he understood little of Vogel’s lectures on photographic principles and aesthetic theory, he reveled in the four hours each week that were devoted to practical work. In 1869 Vogel had founded the Verein zur Förderung der Photographie, Berlin (Association for the Advancement of Photography), a professional organization whose members were admitted by election. At the time of Stieglitz’s own election to the association in March 1885, Vogel embarked on a series of lectures that described the processes used by various German and Austrian photomechanical printing establishments, based on information that he had gathered the previous fall. The association published the lectures in a series of articles in its journal, Photographische Mitteilungen.

Germany in the 1880s was “teeming with amateur photographers,” and Vogel, a staunch supporter of amateurism, founded the Deutsche Gesellschaft von Freunden der Photographie (German Society of the Friends of Photography) in 1887. (Stieglitz was elected a member several months later.) Amateur photography was also booming in Britain and the United States, and, along with it, the publication of magazines devoted to the subject, including The Amateur Photographer (London, 1884) and The American Amateur Photographer (New York, 1889). As the number of periodicals rose so too did rapid advances in photomechanical printing processes as publishers sought inexpensive methods of reproduction. A typical issue usually contained one or two quality reproductions—such as collotype, Woodburytype, or photogravure—but with the refinement of the halftone process, which allowed text and images to be printed on the same page, the number of possible illustrations grew. By the mid-1890s it was common for periodicals to reproduce one or two works, often a frontispiece, using a high-quality process, usually photogravure, and several halftones.

The photogravure process was made possible by Alphonse Louis Poitevin’s significant discovery in 1855—that pigment could be combined with light-sensitive bichromated gelatin to make a print. Poitevin applied his findings to an experimental version of what would later be known as the carbon process, in which pigment (such as carbon black) suspended in bichromated gelatin was exposed to light under a negative, causing the gelatin to harden in areas that received more light, and remain soft in areas that received less light. The unhardened areas dissolved when washed with warm water, leaving a positive image of pigmented gelatin. The method became practical in the mid-1860s when the pigmented gelatin layers (tissues) became commercially available. Poitevin patented his carbon process, and, at the same time, a printing process using lithographic ink and a photographically prepared lithographic stone. Known as the collotype, it was further improved by Joseph Albert of Munich (1825–1886). Albert used glass plates coated with bichromated gelatin over a layer of hardened gelatin and exploited the ability of the gelatin to fracture in a fine reticulated pattern. After exposure to light through a positive image the plate was washed and then printed.

Peter Henry Emerson, Marsh Weeds, in or before 1895, from Marsh Leaves, photogravure on wove paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Harvey S. Shipley Miller and J. Randall Plummer, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art, 1990.113.1.f

The early pioneers of photography Joseph Nicéphore Niepce (1765–1833) and William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) had experimented with photogravure, but it was not until the beginning of the 1880s that Karl V. Klíč (1841–1926) used carbon tissue to make a reversed transparency that acted as an etching resist. Klíč dusted a copper plate with powdered bitumen and fixed it with heat, creating a ground that not only protected the metal but also provided a surface to which the resist could adhere. The negative carbon print was mounted on the prepared plate, exposed to light, and then etched. The plate was then gently heated, inked, and printed using an intaglio (etching) press. Photogravure was preferred by a small but influential group of photographers that included Peter Henry Emerson. Emerson favored the platinum process for his original photographs, but for his published work he felt that the “only satisfying method” of reproduction was photogravure; he even published several large-format photogravures that were sold individually. By 1890 he had learned to etch and print his own plates from the London publisher Walter L. Colls. Although Colls warned him that photogravures were best printed on plate paper (a soft paper that took ink well), Emerson experimented with a range of papers and inks. He wrote: “[I]n etchings of all kinds the choice of papers and inks is most vital.” Emerson and Stieglitz began a lively correspondence soon after Emerson, acting as sole juror, awarded Stieglitz first prize in the 1887 “Holiday Work” competition of The Amateur Photographer.

Stieglitz returned to the United States in the fall of 1890 at the request of his parents after the death of his sister Flora. His father had secured a position for him at the Heliochrome Company in New York, a photoengraving firm run by John Gast, a former employee of William Kurtz (1834–1904). (Ultimately Kurtz was the first to perfect a three-color halftone process.) Although Stieglitz later claimed to have had little interest in running a business, he seems to have been intrigued with photoengraving: in the spring of that year, he had traveled to Vienna to study at the Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt, the state printing and photography school, headed by photo-chemist and historian Josef Maria Eder (1855–1944). Unable to gain admittance to Eder’s photoengraving class in the summer, however, he traveled for a month before returning to Berlin.

Advertisement for the Photochrome Engraving Company, The International Annual of Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin 9 (New York, 1896), unpaginated, Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Washington

Stieglitz restructured the struggling Heliochrome Company under the name Photochrome Engraving Company with two partners, Louis Schubart and Joseph Obermeyer, his former roommates from Berlin. The firm reportedly did not receive a single order the first year; nonetheless, Stieglitz established a printing laboratory and introduced the firm’s employees to new processes. These sessions met with “sullen resentment from all but one of them,” Frederick (Fritz) Goetz. Goetz, an American, had been a member of the Association for the Advancement of Photography during Stieglitz’s tenure. He also had been employed in Kurtz’s studio. Like Stieglitz, he looked forward to the day when the halftone process, which had been in regular use since the 1880s, could be used to achieve color results. Stieglitz saw great potential in the halftone, believing it “ruled the world of illustration” because of its speed and economy as well as its ability to duplicate closely the look of an original photograph. By 1903 the firm could proudly advertise that they could produce “halftones from articles for catalogue work; color-work without the hallmark of the mechanical three-color process; line-work on zinc or on copper; and, in fact, reproductions of every description, large or small, expensive or inexpensive” as well as their specialty, the “king of all processes,” photogravure.

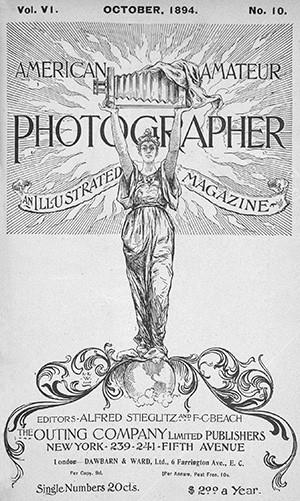

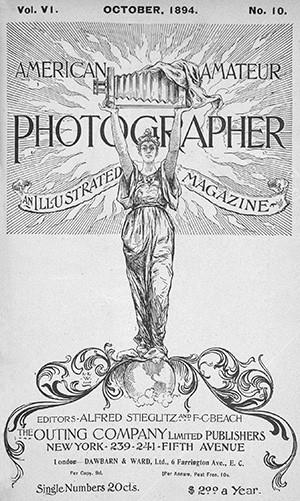

Around the same time, in the early 1890s, Stieglitz regularly published articles in The American Amateur Photographer. In July 1893 he joined Frederick Beach as co-editor. “We have no doubt but what important improvements in the magazine will be undertaken, and will include, perhaps, a greater number and variety of illustrations,” Beach wrote. “[Stieglitz’s] judgment of the value of photographic work is always good, while his technical knowledge . . . is unsurpassed.” Stieglitz’s photographs had earlier appeared in the magazine as photogravures printed by the New York Photogravure Company and the Photochrome Engraving Company had also produced numerous halftones of his work. To herald his firm’s successful achievement of its own color halftone process, Stieglitz reproduced a hand-colored platinum print of The Last Load in the January 1894 issue. Editors Beach and Stieglitz commented that although they did “not, as a rule, favor colored photographs, as they are generally crude and inartistic,” this example was “particularly interesting as a specimen of colored photography.”

Cover of The American Amateur Photographer 6, no. 10 (October 1894), Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Washington

In January 1895 Stieglitz became sole editor of The American Amateur Photographer and he used the opportunity to disentangle himself from the Photochrome Engraving Company. Stieglitz later recalled that, although he “loved fine printing,” he was disillusioned with the photoengraving business, as it demanded “speed and quantity” rather than “careful craftsmanship.” Cheating customers and slipshod practices disgusted him, and he lamented that to sustain the business required “a policeman on one side, a lawyer on the other.” He did nonetheless go on using the firm for halftone work during his tenure at the magazine, at the same time commissioning photogravures from E. C. Meinecke and Company.

Stieglitz severed his connection with The American Amateur Photographer in February 1896 to devote himself to improving the standard of pictorial photography in the United States. He had already joined the Society of Amateur Photographers in New York in 1891; in 1896 the Society merged with the New York Camera Club to form the Camera Club of New York. Stieglitz aspired to lead the Camera Club in sponsoring the finest annual exhibition of photography in the world. From the early 1890s, photographic salons had been organized in the major European centers. To commemorate these salons and allow viewers to “vicariously experience the exhibition,” exhibition organizers published deluxe portfolios, fine books in their own right. The leading group of creative photographers, The Linked Ring, issued an elaborate portfolio, Pictorial Photographs: A Record of the Photographic Salon of 1895, published by Walter Colls and featuring twenty photogravures, including Stieglitz’s Hour of Prayer (published as Scurrying Home, Key Set number 218). Three editions of the portfolio were printed: a regular one, on plate paper; an edition of one hundred, on India paper, a soft, thin paper that was mounted to a second sheet during printing; and an edition of fifty, on Japanese paper. Colls’ photogravures were called “capitally done,” and the portfolio as a whole “one of which not only the Salon and Mr. Colls, but photography itself may be proud.”

Other important publications included the Première Exposition d’Art Photographique (1894), a lavish volume issued in a limited edition of thirty, printed on Japanese paper, as well as a regular edition of 470, printed on white Marais paper, a French mold-made paper with deckled edges on all four sides and a felt-like finish. In the deluxe edition, the recipient’s name appeared on the colophon. The photogravures (including Stieglitz’s Card Players) were printed in a variety of ink colors. The elegant Nach der Natur (After Nature) was published at the request of the German and Silesian Society of the Friends of Photography by the Berlin Photographic Company to commemorate the 1896 “Internationalen Ausstellung für Amateur-Photographie” (International Exhibition of Amateur Photography) in Berlin. Nach der Natur contained thirty-two photogravures (including Stieglitz’s Scurrying Home), each so superb that Stieglitz was moved to proclaim photogravure “the most perfect of all photographic reproduction processes.”

Cover of Picturesque Bits of New York and Other Studies, 1897, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

The exceptional quality and beauty of these publications inspired Stieglitz’s own portfolio in photogravure. Picturesque Bits of New York and Other Studies, published in 1897 by Robert Howard Russell, included twelve prints (see Key Set numbers 83, 109, 115, 120, 148, 154, 174, 183, 220, 251, and 252). The photogravures were printed in an edition of twenty-five on plate paper using different ink colors. “We have been accustomed to see the fine tones and graduations of our best workers so utterly ruined in the process of engraving and printing that we are agreeably surprised at the wonderful delicacy and transparency of these examples,” wrote publication committee member William M. Murray. Winter on Fifth Avenue was “undoubtedly the finest reproduction of the set . . . there is absolutely nothing lost of the finest gradations of the original.” Stieglitz himself made the steel engravings from the diapositives (positives made from negatives), and used rapid plates to preserve the detail and softness of the originals. In addition, he directly supervised the printing of each image.

Cover of Camera Notes 1, no. 1 (July 1897), National Gallery of Art Library, Washington

Stieglitz’s goal was to publish a magazine that would set a new standard of excellence in pictorial photography, which would in turn attract the finest photographers to the club’s yearly salon. The Camera Club intermittently published a leaflet without images, The Journal of the Camera Club. As vice-president of the club, Stieglitz proposed redirecting the $250 budgeted for the Journal to the publication of a quarterly. He argued that by selling advertising space, the Camera Club could afford to produce a substantial, beautifully illustrated periodical. The membership greeted his proposal with enthusiasm and he was appointed chair of the publication committee and editor. The first issue of the new magazine, Camera Notes, appeared in July 1897 in two editions: a regular edition of one thousand on plate paper and a deluxe “Booklovers” edition of ten on Indian paper. Stieglitz proposed including two photogravures with each number, “representing some important achievement in pictorial photography; not necessarily the work of home talent, but chosen from the best material the world affords.” In addition, halftones would occasionally illustrate articles of interest. The regular column, “Our Illustrations,” informed readers that the Photochrome Engraving Company had printed the photogravures of the American contributors, while Walter Colls had printed those of the Europeans. The exception was the work of J. Craig Annan, which was printed by his own firm, T. & R. Annan and Sons, Glasgow. Camera Notes was pronounced “better than any of its contemporaries on this side of the water” in one respect, at least. “We allude to its promise to give us two photogravures in each number . . . [F]rom what we know of those responsible for the Camera Notes, every one of its photogravures will be a work of art.”

In the first two issues of the journal Stieglitz featured photogravures of his own works made several years prior, Portrait of Mr. R. (1895) and A Bit of Venice (1894). Two years later, he included another earlier work, Mending Nets (1894). It proved to be a “most difficult picture to reproduce effectively” and “unfortunately lost much of its quality and charm in the reproduction.” The difficulty may have been owed to the inability of the photogravure process to capture the heavily textured watercolor paper on which the original photograph was printed (Key Set number 212). In the late 1890s, Stieglitz had been experimenting with painterly effects using carbon, manipulated platinum, and gum bichromate processes, and the halftone process allowed for a more successful depiction of the color and texture of these prints.

Stieglitz included several photogravures in an exhibition of his photographs at the Camera Club in May 1899. It was his intention to “tell truthfully the story of his work from its beginning to the present time.” The result of nearly fifteen years of “constant and serious labor in the field of pictorial photography,” the exhibition traced his career through images as well as processes, and included Aristotypes, platinum prints, carbon prints, and gum bichromate prints along with photogravures. To commemorate the exhibition, Stieglitz published a “refined and elegant example of the printer’s art” to represent “his idea of what a catalogue should be.” On the cover of the catalogue was a photogravure of Gossip—Katwyk.

As head of the Camera Notes publication committee, Stieglitz issued a limited edition of 150 portfolios in the fall of 1899 to exemplify the “most characteristic examples of the work of those Americans whose names are best known to the club or whose influence has been most pronounced on the development of pictorial photography in America.” Additional works were to be added to the portfolio over time so that ultimately the complete series would be the most “representative collection of pictures ever published, and should be in the hand of every serious student of pictorial photography, not alone as a record of representative American work, but because of the exceptional opportunity afforded by it of perfecting one’s own work through the careful, conscientious study of that or others.” The portfolio, American Pictorial Photography, featured eighteen photogravures printed on Indian paper (including Stieglitz’s Reflections—Venice and Early Morn), along with a title page and table of contents printed in red and black on Japanese paper, all enclosed within green cloth covers stamped in gold with the seal of the Camera Club. The name of the subscriber and the number of the copy were printed on the reverse of the title page, and each copy was countersigned by Stieglitz. Arranged, engraved, and printed by the Photochrome Engraving Company, the photogravures were “so remarkably executed as to deceive the eye into the belief that they are original platinum and carbon prints and not merely reproductions therefrom. The engravers have every reason to feel proud of their work, which has attracted great attention wherever shown, and which deserves to be ranked with, if not as, the best work of the kind ever done in this country.”

In the late 1890s Stieglitz began a series of photographs of New York that would explore the city’s “myriad moods, lights, and phases,” a theme he would revisit throughout his career. Several works from this series were published as photogravures in Camera Notes, beginning in October 1901 with An Icy Night (1898) and continuing in January 1902 with Spring Showers: the Coach (1901) and Spring Showers: the Sweeper (1901). Stieglitz seems to have printed the two Spring Showers as well as another image made around this time, The Flatiron (1903) (Key Set number 288), only as small- and large-format photogravures. He may have intended to include the large-format prints in a portfolio that was to have been titled Fifty Prints of New York, which was never published. He was simultaneously working on a second series about his daughter Kitty (born 1898) and others. One image from this series, a portrait of Kitty titled Spring, was also reproduced in the January 1902 number.

Under mounting criticism that Camera Notes was becoming an elitist publication whose contributors were mostly from outside the club, Stieglitz published a valedictory in July 1902 to announce that “after the publication of this number, the management of Camera Notes, under whose auspices the magazine was founded and developed, finds it impossible to continue its labors.” Almost immediately he began to plan a new publication that would owe allegiance “only to the interests of photography” yet would serve as the “mouthpiece of The Photo-Secession,” signifying his alliance with European groups that had revolted against the old guard. The magazine would begin as a quarterly and, to ensure its independence, would be edited and published by Stieglitz. It was his aim to make the new journal, Camera Work, “the best and most sumptuous of photographic publications.” Before the first number appeared in January 1903, he had 627 subscribers.

Advertisement for The Work of Alfred Stieglitz, from Camera Work 5 (January 1904), unpaginated, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

Stieglitz took great care with the quality of the illustrations for each number of Camera Work. He carefully supervised all aspects of the printing, initially accomplished almost exclusively by the Photochrome Engraving Company, and in the column “Our Illustrations” he regularly praised the firm for the sympathetic manner with which the photographs were reproduced. The work of British photographers was printed by T. & R. Annan and Sons while the European work was printed by F. Bruckmann Verlag in Munich, now headed by his old friend and former collaborator from the Photochrome Engraving Company, Fritz Goetz. Stieglitz saw photogravures not as reproductions but rather as equivalents of the original prints, as they were made “directly from the original negatives and printed in the spirit of the original picture and retaining all its quality.” To prove the point he issued a limited edition of a set of large-format photogravures in January 1904 that was intended for both individual sale or for sale as a group. The set, The Work of Alfred Stieglitz, consisted of five prints on thin Japanese paper in an edition of forty. Included was one image from his 1894 European trip (Key Set number 122); an enlarged version of the portrait of Kitty that had appeared earlier in Camera Notes (Key Set number 273); and three works from his continuing series of pictures of New York (see Key Set numbers 267 and 269).

Several times in the early numbers of Camera Work, Stieglitz had published individual works from his New York series (Key Set numbers 258, 266, 277, and 287), and in October 1905 he issued the first number devoted to his own work. The portfolio included early and more recent work printed in halftone (Key Set numbers 209 and 250) and photogravure (Key Set numbers 85, 274, 291, 293, 295, 296, 299, and 306). The halftones were treated in a similar manner to the photogravures; that is, placed singly on the page with no text. The original photographs were a carbon and a gum print and presumably reproduced more faithfully using the halftone process. The Manhattan Photogravure Company, headed by Stieglitz’s former partner Louis Schubart, printed the photogravures. The company had been founded the previous year after the photogravure division split from the Photochrome Engraving Company. (Stieglitz continued to employ the Photochrome Engraving Company for the halftone work.)

Stieglitz intended Camera Work to appeal to those who believed in photography as a medium of individual expression and also to showcase photography’s possibilities. The reproductions illustrated the variety of the mechanical printing processes available during the first quarter of the twentieth century. Edward Steichen’s Autochrome plates, featured in the April 1908 issue, were among the first published examples of the four-color halftone process using color transparencies. Because of their irregular color structure, it was felt that Autochromes could not be reproduced. During his European travels in the summer of 1907, Stieglitz engaged F. Bruckmann Verlag to print the edition. Their early efforts proved unsatisfactory: “an unfortunate chain of circumstances” prevented the firm from keeping its promise to have the edition completed before December. Three sets of blocks were made before any acceptable results were achieved, and, in the end, only three of the four proposed images appeared in the April number. The reproductions of Heinrich Kühn (1866–1944) in a later number (January 1911) were also printed by Bruckmann, illustrating the “possibilities of the various photomechanical processes used today in reproducing photographs: photogravures, intaglio plates printed by hand; mezzotint photogravures, printed by steam; [and] duplex-halftones (two printings).”

Stieglitz made large-format photogravures of his work periodically, through 1913, that may have been intended for inclusion in his portfolio of New York images. Many of these large prints were included in important exhibitions, such as the 1910 “International Exhibition of Pictorial Photographs” at the Albright Art Gallery, and his one-man exhibition at the Photo-Secession Galleries in 1913. Small-format versions of some of these images were published in 1911 in the second issue of Camera Work devoted to his own work (Key Set numbers 93, 279, 331, 334, 341, and 344). Included in this group was The Steerage (Key Set number 310), another image that Stieglitz intended as a photogravure only. “I had in mind enlarging it for Camera Work, also enlarging it to eleven by fourteen and making a photogravure of it. . . . Two beautiful plates were made under my direction . . . proofs were pulled on papers that I had selected.” The Steerage was also featured in the September/October 1915 issue of the proto-dada magazine 291, edited by Marius de Zayas, Paul Haviland, and Agnes Ernst Meyer under Stieglitz’s sponsorship. Five hundred photogravures were printed on Japanese vellum and a deluxe edition printed on thin Japanese paper (Key Set number 313). The regular edition was offered for two dollars; the price of the deluxe edition was available on request. About one hundred people subscribed to the regular edition and eight to the deluxe. No other copies were sold. Stieglitz later claimed to have sold the remaining copies, including prints of The Steerage, to a rag picker during the war, for five dollars and eighty cents.

Paul Strand, Alfred Stieglitz at His Press, New York, c. 1920, printed early to mid-1980s, gelatin silver print, Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Paul Strand Collection, partial and promised gift of Marguerite and Gerry Lenfest, 2009-160-43. © Aperture Foundation, Inc., Paul Strand Archive

At its inception Camera Work was issued in an edition of one thousand, but by the end of its run in June 1917 the size of the printing had fallen to less than five hundred, and the number of subscribers had dwindled to thirty-six. Stieglitz was driven “to despair” by the Manhattan Photogravure Company—“If it were not for the Bruckmann people in Munich and Craig Annan in Glasgow, I would have had to give up Camera Work long ago.” Unable to send work to his friend Fritz Goetz at the Bruckmann firm and with his income severely depleted with the onset of the war, Camera Work came to an end. He later destroyed many of the remaining issues—“I just couldn’t take care of them anymore.”

The care that Stieglitz lavished on each original photograph extended to a reproduction made from that photograph, which he saw as a vehicle to disseminate not only his images but also photography’s artistic potential. “Many of my prints exist in one example only . . . there is no mechanicalization, but always photography,” he wrote in 1921. “My ideal is to achieve the ability to produce numberless prints from each negative, prints all significantly alive, yet indistinguishably alike, and to be able to circulate them at a price not higher than that of a popular magazine, or even a daily paper.” In later years, Stieglitz denied many requests from commercial publications for permission to reproduce his photographs. Enormous changes had occurred not only in photoengraving but in his own work as well—he increasingly used silver “postal card” stock after 1924—and he believed that he would have to get back into the business himself to find out how his photographs should be reproduced. “The quality of touch in its deepest living sense is inherent in my photographs. When that sense of touch is lost the heartbeat of the photograph is extinct. In the reproduction it would become extinct—dead. My interest is in the living.”

Originally published 2002; minor adaptations have been made for the presentation of this text online.