Emerson gave Stieglitz license to move beyond the literalness and undigested inclusiveness of the snapshot and encouraged him to look at other painters. He frequently praised the art of Theodore Rousseau, Jean Baptiste Camille Corot, Jean-Francois Millet, Jules Breton, and especially Jules Bastien-Lepage, whose paintings composed of areas of suggestively broken brushstrokes and passages of almost photographic detail illustrated the photographer’s own theories of visual perception. Stieglitz approvingly cited both Millet and Bastien-Lepage’s work in his published writings in 1893 and purchased a copy print of the latter’s October Season: The Potato Harvest, 1879.

The Key Set: 1884–1901

Sarah Greenough

Here is the dividing line between a photograph and a picture.

Alfred Stieglitz, 1892

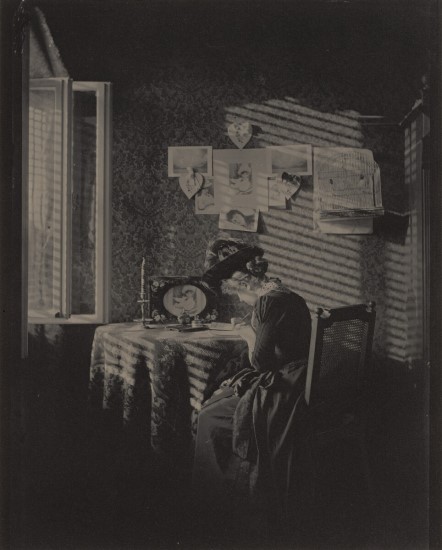

Alfred Stieglitz, Sun Rays—Paula, Berlin, 1889, printed 1916, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.57

Key Set number 60

Like any enthusiastic beginner, Stieglitz photographed avidly when he was a student in Berlin in the 1880s, yet much of his work from this time is known only through reproductions or as titles in exhibition checklists and reviews. The Key Set includes sixty-one vintage photographs from 1886 through 1890, but only six are exhibition prints; the rest are bound into six albums. Although the albums contain an eclectic mix, two photographs in particular illustrate the dominant issues in his work from this period. The first, Relief of Queen Louise, Berlin, 1886, is a study of the base of a statue, an exercise in recording contrasts of light and shade, and texture and pattern (Key Set number

In later years when he no longer felt compelled to validate photography by comparing it to anything else, Stieglitz tried to discount any influences on his early work, suggesting that photography and life, not painting or any other art, were his inspiration. In 1922 he claimed that he “knew nothing about painting” before 1905, and in 1935 told E. M. Benson that from his earliest years when he went into most museums, they “‘smelt like old leather’” and he longed to escape “‘into the street.’” Stieglitz was clear, Benson continued, “if a photograph reminded you of a painting, then it was neither one nor the other. . . . It was easy for him to believe this. Since he knew very little about plastic traditions, his vision was formed not by seeing art, but by seeing life.”

To a certain extent photography was, as Stieglitz said, his muse. When he began to photograph, probably in 1884, the medium captivated and challenged him as nothing else had done before.

Stieglitz deeply admired Vogel and rapidly assimilated his teachings. As Vogel directed, he tackled a wide variety of subjects—landscapes, genre studies, portraits, including one of Vogel himself—and he also photographed works of art (see, for example, Key Set numbers

Yet, despite his assertions to Benson in 1935, Stieglitz, was, even as a child, deeply immersed in the “plastic traditions.” His father, Edward Stieglitz, a successful businessman and amateur painter, collected art and artists, and the young Alfred was very much a part of his father’s world (see Key Set number

Figure 1

Alfred Stieglitz, The Card Players, 1886, platinum print, private collection

Figure 2

Eduard von Grützner, The Card Players, 1883, oil on canvas, Milwaukee Art Museum, Gift of René von Schleinitz, M1967.67. http://www.mam.org, Photo: Larry Sanders

Displaying the worldly air of a young student, Stieglitz frequently referred to the work of all these artists in his writings of the time, and, when he began to photograph, he quickly found that he could easily replicate their anecdotal, narrative, and picturesque subject matter.

Figure 3

Alfred Stieglitz, The Last Joke—Bellagio or A Good Joke, 1887, platinum print, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949.3.30

Key Set number 33

Figure 4

Ludwig Passini, A Tasso Reader, 1871, engraving after the painting, from Wilfrid Meynell, ed., Modern Art and Artists (London, 1887), 188

While the subject matter for many of Stieglitz’s photographs made between 1886 and 1890 derived from contemporary painting, in important ways they were fundamentally different. His photographs were frequently more direct, literal, rooted to a particular time and place, and as the photographer Peter Henry Emerson noted when he awarded The Last Joke first prize in an 1887 competition, they were “spontaneous,” not contrived.

When Stieglitz returned to the United States in the fall of 1890, he immersed himself in the things that had nurtured him in Germany: his own photography, the chemical and technical experiments that so intrigued him, and the work of other artists. He joined the Society of Amateur Photographers of New York, and, most likely because lantern slide presentations were such an integral part of American camera clubs, began to explore this process in 1891. Encouraged by a fellow club member, William B. Post, he began to photograph with a small hand-held camera in 1892.

Figure 5

Alfred Stieglitz, Studying “High Art” while Waiting for a Car, 1892/1893, lantern slide, location unknown

Figure 6

Alfred Stieglitz, An Hour after the Snowstorm, 1896/1899, gelatin silver print, Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona, Tucson, The Herbert Small Collection

Winter, Fifth Avenue, 1893—the earliest vintage exhibition print from Stieglitz’s New York years in the Key Set—was also his first hand camera photograph to make the leap from nature, or document, to art, but only after it had been extensively reconstructed (Key Set numbers

The transformation of Winter, Fifth Avenue reflects the influence of the American expatriate Peter Henry Emerson. In his highly controversial book Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art, 1889, Emerson insisted that camera vision was different from human vision, which selectively focuses on only one object at a time, according to its inherent interest, color, or prominence. Urging photographers to transcend their machines and their sharply detailed mechanical transcriptions of nature to render instead an impression of nature, Emerson ridiculed the idea of compositional rules. “Selection,” he maintained, “is one of the most—if not the most—vital matters in the art of photography.”

Figure 7

William B. Post, The Critic, 1894, platinum print, Princeton University Art Museum, Museum purchase, bequest of Blanche Adelaide Hungerford Latimer Icaza in memory of her parents, Walter Rowland Latimer and Blanche Rodney Crowther Hungerford, 1995-121

Figure 8

Max Liebermann, Die Netzflickerinnen (The Net Mender), 1887/1889, oil on canvas, Hamburger Kunsthalle. bpk Bildagentur / Hamburger Kunsthalle / Elke Walford / Art Resource, NY

In 1894 when Stieglitz traveled to Europe, he was a significantly different—more certain and directed—photographer than he had been when he left four years earlier. Like so many painters of the time—Gauguin most famously—Stieglitz on this trip searched for authenticity in cultures less technologically developed than his own: “I dislike the superficial and artificial,” he said in 1896, “and I find less of it among the lower classes.”

Figure 9

Wilhelm Hasemann, Wafferhäusle, from Wilhelm Jensen, Der Schwarzwald (Berlin, 1890), 87

Stieglitz visited his friend Hasemann in Gutach where he worked alongside the painter in his studio, photographing the same subjects, perhaps even the same people. (Compare, for example, Stieglitz’s Sunlight Effect to Hasemann’s own depiction of the subject, Key Set numbers

He also returned to Venice. Turning away from the melodrama of Passini, he sought the everyday aspects of the city: a tramp asleep at six in the morning on the Piazetta near the Piazza San Marco, a solitary woman crossing the Ponte della Paglia, or women drawing water from wells (Key Set numbers

The photographs Stieglitz made on his 1894 European trip established him as one of the leading photographers of the time. Like other contemporary pictorial photographers—Heinrich Kühn or Robert Demachy, for example—he utilized every tool available to transform these photographs into impressive exhibition pieces that would be immediately understood as works of art.

For the next dozen years, Stieglitz repeatedly showed his 1894 photographs in exhibitions and illustrated them in periodicals in both this country and in Europe: between 1895 and 1907 he exhibited and reproduced Gossip—Katwjk at least thirteen times, while he exhibited The Net Mender nineteen times and reproduced it sixteen times. He was also highly attuned to the critical reception of his work. In 1895 after the director of the National Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels selected Scurrying Home as one of a few photographs purchased for a future National Collection of Pictorial Photographs, Stieglitz included it in almost every exhibition he entered for the next seven years, showing it twenty-one times before 1903.

These photographs also formed the core of Stieglitz’s first one-person exhibition at the Camera Club of New York in 1899: more than one third of the works shown were made on his 1894 trip to Europe. Surprisingly, less than one third were made in the following three years. Although he continued to assert that in “proper hands . . . lens, camera, plate, developing-baths, printing processes” were simply “tools for the elaboration of their ideas,” not “tyrants to enslave and dwarf them,” increasingly he appeared more interested in the process than the ideas and he seemed to lose his sense of direction: although he photographed his daughter Kitty, he made few other new pieces.

Instead, he returned to a subject that would sustain him, if sporadically, for the rest of his career: New York.

Stieglitz, as always, responded to this praise. Approaching the subject cautiously, he did not strive to construct a new vision for the new city blossoming around him, but instead made it conform to notions of the picturesque so that it became more familiar. “Metropolitan scenes,” although “homely in themselves,” could have “a permanent value,” he wrote in 1899, if “the poetic conception of the subject” was revealed.

Figure 10

Childe Hassam, Late Afternoon, New York, Winter, 1900, oil on canvas, Brooklyn Museum, Dick S. Ramsay Fund, 62.68. Photo: Brooklyn Museum

When Hartmann praised Stieglitz’s photographs of New York City in the late 1890s, the photographer told him that one of his favorite artists was the Norwegian Frits Thaulow.

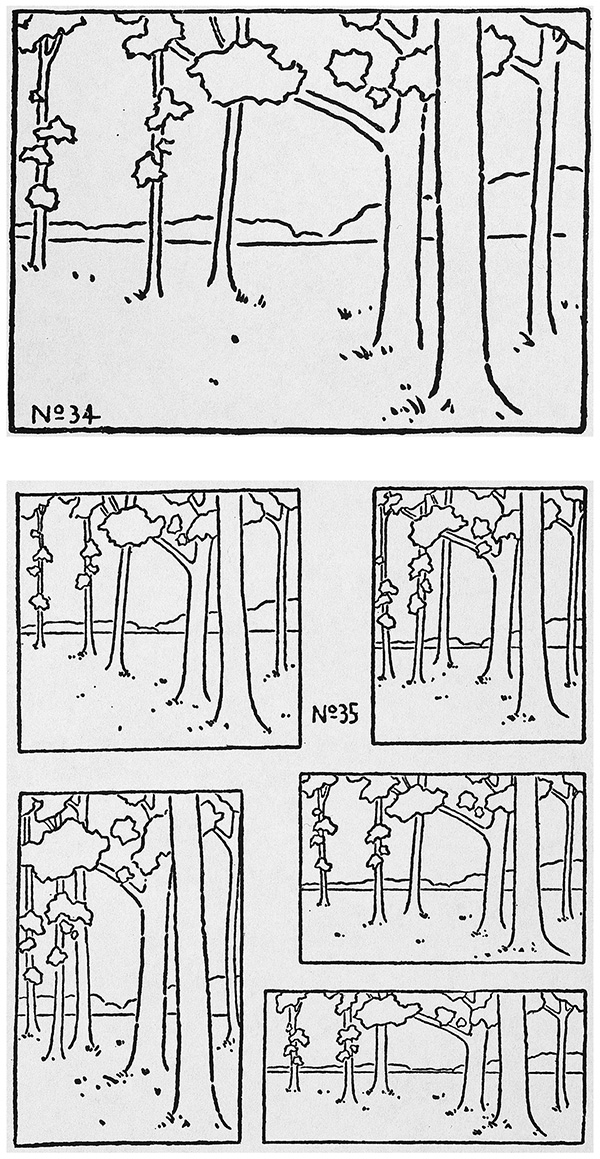

Figures 11, 12

Arthur Wesley Dow, Exercise Nos. 34 and 35–Landscape Composition, from Composition: A Series of Exercises in Art Structure for the Use of Students and Teachers (New York, 1900)

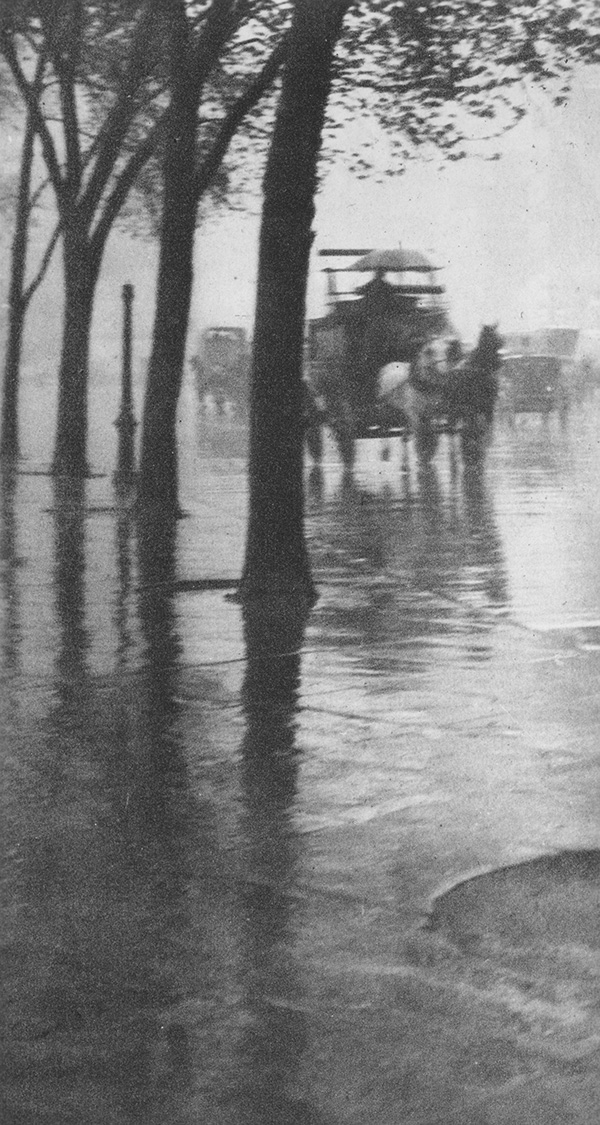

Figure 13

Alfred Stieglitz, Spring Showers—The Coach, 1899/1901, from Camera Notes 5 (January 1902), 182

Scribner’s Magazine published several of Stieglitz’s photographs of New York in 1903, along with an essay by John Corbin on “The Twentieth Century City.”

Shortly after the turn of the century, Stieglitz thought of publishing two portfolios. In one, he wanted to reveal New York in “myriad, moods, lights, phases,” as a city “of transition—the Old gradually passing into the New.”

Previous: The Key Set | Next: 1902–1917

Originally published 2002; minor adaptations have been made for the presentation of this text online.