Megan R. Luke

Sculpture in an Age of Mass Reproduction: Untimely Objects of Modern German Art and Media Theory

Today it is possible to store any object as digital data in the cloud, where it waits, invisible and intangible, until it is printed into synthetic polymers on demand. Search for any prominent monument in the public domain, and you may well find enough information online to fabricate a detailed computer model, eliminating any need to scan it directly. Photogrammetry software and additive manufacturing techniques indulge an enduring fantasy of a history of art without loss. As these technologies become cheaper, more user-friendly, and seemingly more “advanced,” they serve an archaic need to touch and possess what we would otherwise only ever access visually through photographic surrogates or the protective glass of museum vitrines.

Oliver Laric, Beethoven, 2016, stereolithography, polyamide, and aluminum base, installed at the Secession, Vienna. Photo: Megan R. Luke

At a moment when any object can appear to be everywhere and nowhere at the same time, what form must sculpture take to enliven the past in perception, and where, exactly, does this encounter take place or belong? Digital technologies facilitating the production, storage, and networked circulation of material culture intensify the doubt, even anxiety, these questions express, while debates about the legitimacy of public monuments and the restitution of artifacts expropriated through conflict and colonization erupt with renewed urgency. Yet we have inherited these concerns, and the language and ideas we use to respond to them, from the history of sculpture in industrial modernity. My book manuscript, “Sculpture in an Age of Mass Reproduction,” tells the story of how sculpture lost its hold over collective memory and cultural identity to become the conflicted object within critical discourse it remains today. In this account, it is an art that appears especially vulnerable to the distortions of mass reproduction and yet whose corporeality may still offer a powerful antidote to systems of automation and the increasing autonomy of artificial intelligence.

Focusing on German art and media theory between 1890 and 1940, I show how an entire ecology of facsimile reproductions remade the sculptural object and its ability to mediate past and present experience. In this cultural context, debates about the relationship between embodiment and history raged within the novel institution of the ethnographic museum, galvanized the new disciplines of developmental biology and experimental psychology, and ultimately yielded innovative methods for the study of art history and visual culture that remain highly influential to this day. My interventions into modern art and intellectual history are twofold. First, I tackle the following question: What can the history of sculpture teach us about the effects of technologies of mass reproduction on our understanding of the past? We might imagine that digital technologies offer new potential to resurrect cultural heritage that has succumbed to forces of destruction or deterioration, iconoclasm or indifference. Yet the desires these recent technologies seek to fulfill have a longer history, one that is only partially described when we limit our attention to photographic images. Second: How did technologies of mass reproduction transform the definition of sculpture, its historicity, and the protocols governing its perception? In my research, modern sculpture is not defined by its singularity, nor by its autonomy from standardized commodities and architecture. Rather, the same industrial technologies that began to reinvent sculptural process and perception in the late 19th century also newly visualized and reconfigured its history for expanding audiences—with profound consequences for our understanding of how sculptural objects give shape to time.

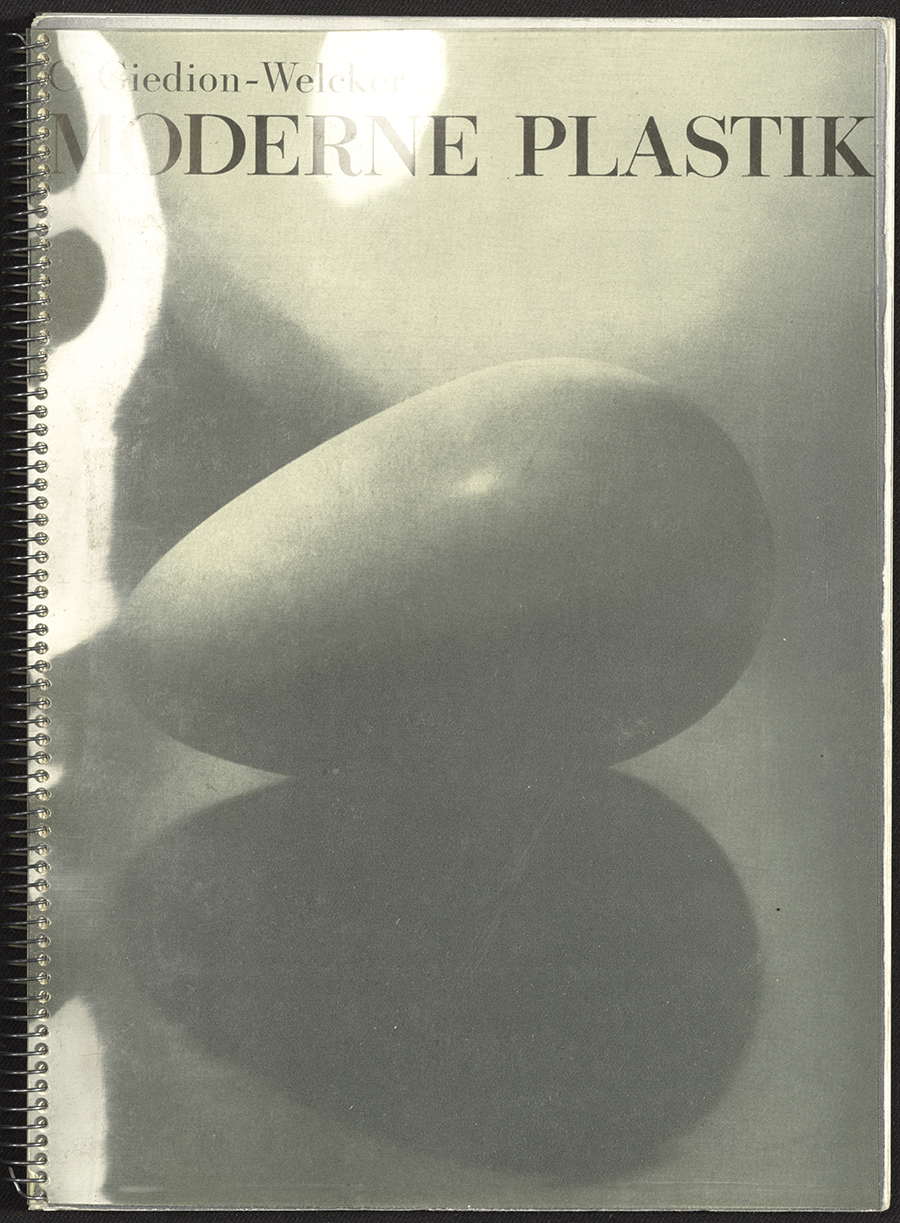

Carola Giedion-Welcker, Moderne Plastik: Elemente der Wirklichkeit, Masse und Auflockerung, 1937, spiral-bound luxury edition with plastic cover (designed by Herbert Bayer with a photograph by Edward Steichen of Constantin Brâncuși’s Beginning of the World [c. 1920]), Bibliothek Carola Giedion-Welcker, Schweizerische Institut für Kunstwissenschaft, Zurich. Photo: Courtesy of SIK-ISEA, Zürich

“Sculpture in an Age of Mass Reproduction” takes up crises confronting the monument, the museum, the photographic archive, and the writing of history in turn. Chapter 1 tackles the problem of “kitsch” through the 1902 Beethoven monument by Max Klinger, its synthesis of opulent materials and industrial techniques, and its remediation through photographs, licensed reductions, and recent works of contemporary art. Chapter 2 links the widespread debates about the display of plaster casts and electrotypes in the Weimar Republic to a broader critique of linear models for narrating history, which motivated contemporaneous proposals for site-specific museum installations by Ernst Barlach and László Moholy-Nagy. Chapter 3 describes the model for sculptural experience offered by the photobooks of Albert Renger-Patzsch, which exacerbated concerns about the reification of organic life in the “ersatz” visual and literary culture of the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit). And Chapter 4 analyzes the pathbreaking visual histories of modernist and prehistoric sculpture published by Carola Giedion-Welcker, which she conceived in dialogue with Hans Arp and James Joyce in the shadow of the National Socialist campaign against “degenerate” art. Taken together, they shed light on a sculptural tradition that critically reflects on its own historicity through technologies of reproduction—a tradition that persists in sculptural praxis today.

University of Southern California

William C. Seitz Senior Fellow, 2022–2023

Beginning in July 2023, Megan R. Luke will join the faculty of the Universität Tübingen as professor and chair of modern and contemporary art history. She will continue her affiliation with the Visual Studies Research Institute at the University of Southern California as a member of Images Out of Time: Visual and Material Culture in a Digital Age, an initiative supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities.