Benjamin O. Murphy

Second-Order Images: Reflexive Strategies in Early Latin American Video Art

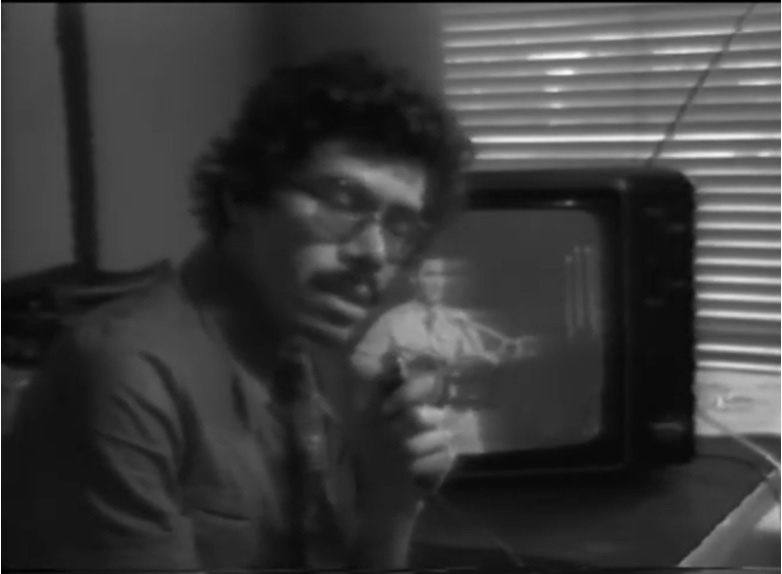

Jonier Marin, VIDEOPOST, 1977, black-and-white U-matic video, Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo

My research at the Center has focused on my current book project, which investigates the emergence of video as an artistic medium in Latin America during the 1970s. Looking at a wide range of artists and institutions based in the Southern Cone, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela, as well as Latin American artists living in exile in Europe and the United States, the project examines how diverse actors used a novel recording technology to respond to the conditions of political oppression under the military dictatorships that ruled across much of the region during this period. I contextualize these artistic experiments within the cultures of commercial television that were rapidly expanding in Latin America at this same moment, exploring how artists both mimed and subverted television’s broadcast infrastructure so as to build networks of political solidarity across the region. Through my research, I show that these artists often coupled such interventions into television’s broadcast procedures with forays into the social sciences and their attendant research methods, employing video technology to conduct sociological surveys, ethnographic fieldwork, and other forms of social documentation and data collection. I place these experiments in dialogue with contemporaneous developments in Latin American sociology, anthropology, communication studies, and political science. In so doing, I demonstrate how video art contributed critically to key discourses animating Latin American intellectual history during the 1970s.

Through this interdisciplinary lens, my book enriches our understanding of the relationship between art and politics during the era of Latin American authoritarianism. Video, I argue, not only furnished artists with strategies for expressing and acting upon these political circumstances; it also served as a platform for reflexive questions about how politics could be represented, and about whether such representational practices might in turn perform political functions of their own. Early Latin American video art was thus aligned with a growing postwar movement across the social sciences toward a paradigm of second-order observation, a position from which those sciences had begun to take their own instruments, postulates, and histories as primary objects of their own analyses. Bringing this reflexivity to bear upon the concept of Latin America itself, the artists I study offered a critical view of how that geopolitical category was constructed by the sciences that purported to observe it. Furthermore, they suggested how that category could be reconfigured for purposes of political solidarity through subversive strategies of disseminating and circulating screen images. The book thus denaturalizes the concept of Latin American art as a given disciplinary subfield, focusing instead on how artistic practice served as a key arena within which the idea of Latin America itself was constructed, scrutinized, and contested.

Jonier Marin, catalog for VIDEOPOST, 1977, printed paper cards and box, Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo

During my time at the Center, I have focused my research specifically on questions of access that framed video art’s emergence in Latin America, and that continue to bear upon our interpretation of it today as they shape and inflect the historical archive. Video technology remained prohibitively expensive in the Latin American region throughout the 1970s; Latin American artists did not enjoy anywhere near the same level of access to equipment as their counterparts in the United States and Europe. They thus negotiated these conditions of precarious and limited access through a piecemeal, multimedia approach that attempted to extend and simulate the properties of that cutting-edge, yet still largely out-of-reach technology through combinations with cheaper, more easily accessible mediums and systems of circulation. By joining video with such readily available supports as paper, photography, and even film, these artists effectively articulated a low-tech form of that novel property so apparently unique to video—that of broadcast. And by thus centering issues of technological limitation in these improvised strategies of broadcast, they critically theorized the geopolitical asymmetries that structured the global configuration of new media. These multimedia practices, finally, require a shift in orientation toward the archive. Much of the corpus of early Latin American video exists today in fragmented form and often only through the secondary traces offered by documentation in other media. And while this state is due in many cases to ex post facto problems of archival preservation, in many other cases it is in fact an original result of precisely those piecemeal, improvised strategies that Latin American artists devised for negotiating their limited access to video. My study thus proposes to rethink the relationship between the archive and the “art” which it documents by attending closely to how Latin American artists effectively archived their own practice—how they introjected processes of archivization into their art-making—through their combinations of video with other media.

A. W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow, 2022–2024

Benjamin O. Murphy will continue his A. W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Center during the forthcoming 2023–2024 academic year.