Anthony J. Meyer

The Givers of Things: Tlamacazqueh and the Art of Religious Making in the Mexica and Early Transatlantic Worlds

Religious leaders—known in Nahuatl as tlamacazqueh or “the givers of things”—both lived in and managed the sacred precinct of Tenochtitlan, the former capital of the Mexica Empire (1325–1521). With wood, bark, sap, and ceramic molds, they would often gather to create sculptures like those of the sacred rain figure, Tlaloc. On wooden rods, they would place sticky bits of fragrant sap called copalli, building layers with finger pressure and heat. Then, lodging the mass into a ceramic mold, they would imprint features and seal the sculpture in white stucco. Once dry, the sculptures were later painted in bright colors and dressed in garments that religious leaders had cut and shaped from wood and fig bark. Leaders would then wrap the sculptures with a rolling smoke that fell from handheld censers and bury them into the precinct floor where they sat until their later excavation in the 20th century. While these sculptures have been studied by Mexican archaeologists, their makers—the religious leaders who cut, placed, and wrapped these works—have remained buried in studies of Nahua art and religion.

Nahua artist(s), Sculpture of Tlaloc, late 15th century, copal, wood, and pigment, Museo del Templo Mayor, Mexico City. Photo: Anthony J. Meyer

Though religious leaders were responsible for making the artworks that filled Mexica offerings and ceremonies, they have largely been left out of art-historical scholarship. This exclusion, in part, is due to how these figures were discussed by 16th-century Iberian authors, who often showed little understanding of their artistic practices and even attacked them as idolatrous. As a result, scholarship has overlooked these makers in favor of better-known state artisans who produced durable works made of monumental stone, feathers, and metals that more closely adhere to Euro-American categories of art. As the Mexica canon took shape in the 20th century, collectors also sought out these durable, monumental works in lieu of the scant, more ephemeral works made by religious leaders.

My dissertation, which I completed and submitted while in residence at the Center, confronts this erasure by re-centering the tlamacazqueh to reclaim the role of makers and making in Nahua religion. Embracing an interdisciplinary, multimedia approach, I analyze both ancestral and early colonial texts, visuals, and objects, as well as the 16th-century Nahuatl language, to unfold a Nahua view of religious making and disentangle the material and spatial worlds that religious leaders created. The tlamacazqueh developed and mastered technical expertise to create religious artworks that drew on the bodily senses, which in turn animated Nahua religion. As I argue in my dissertation, these skills were part of a Nahua concept of artistry known as tōltēcayōtl. Over individual chapters, I map the places where these religious leaders learned (īxtlamachtiā) their skills; how they cut (tequi) materials and created new forms with flint knives; how they molded doughs and folded fig bark to place (tlāliā) and present sacred energies; and how they wrapped (quimiloā, ilpiā) religious art with smoke and woven fibers to give them the ability to perceive.

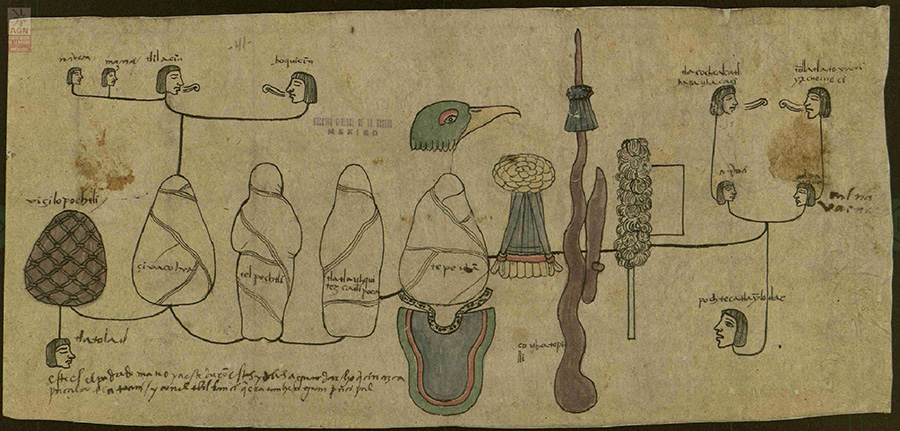

Mateos [a Nahua painter], Sacred Bundles from the Inquisitional Trial of Miguel Pochtecatl Tlaylotlac, 1539, pigment on paper, Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico City. Photo: Archivo General de la Nación, used with permission

The boundary between these makers and their made things was often slippery. In the Nahua world, as in many ancestral communities, beings were understood in relation to one another. As my project asserts, Nahua makers and made things must be treated as inseparable and equal beings, understood in relation to and part of one another. I intervene by centering the religious makers who manipulated materials and their energies to bring sculpture to life, as well as dealing with how these made things, in turn, interacted with and animated their makers. Indigenous theories of relationality, which are often ignored in Euro-American research paradigms, help to unpack the relationships, knowledge, ecologies, and imperial networks that constellate around both makers and made things.

Since religious leaders and their practices did not suddenly vanish after the Mexica Empire fell in 1521, my research also follows them into the early years of Iberian occupation. In fact, the tlamacazqueh took drastic measures to protect religious artworks in the fallout of war, and they acted as community mediators and practitioners who maintained and passed on their skills and knowledge. Inquisition trials, ecclesiastical records, and proto-ethnographic surveys of Nahua culture all trace these histories of caretaking, as well as the religious, artistic, and epistemological networks that remained at play well into the colonial period. By straddling these pre- and post-Invasion worlds, my project forges a novel path in scholarship on the Indigenous Americas to shed light on how religious leaders disseminated, presented, performed, and essentially made two imperial religions: one Mexica and the other Ibero-Christian.

University of California, Los Angeles

Andrew W. Mellon Fellow, 2021–2023

Following his residency, Anthony J. Meyer will begin working on his first book project as a fellow in Pre-Columbian Studies at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC.