Angela Ho

Defining Self and Other: The Dutch East India Company’s Encounters with Chinese Culture, 1602–1740

To the educated burghers of the early modern Dutch Republic, China represented many things at once: an empire of prosperity and enlightened governance; a source of exotic, technically superior crafted goods; and a lucrative business opportunity. The first Dutch merchant ships, following the sea route charted by the Portuguese a century earlier, reached the South China Sea in the 1590s. Just a few years later in 1602, the States General chartered the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC), which was granted monopoly over Dutch trade from the Cape of Good Hope to Japan. Despite setbacks in their attempts to petition the Ming and Qing governments for direct trading rights in China, the VOC was able to trade in Chinese products through its extensive shipping network in East Asia. Indeed, the Company imported unprecedented volumes of luxury goods from China in the 17th and 18th centuries, making them accessible to wide swaths of the Dutch population beyond the elite. The contacts established between the VOC and diverse Chinese groups, as well as the crafted objects circulated in trade, inspired artistic innovations in both cultures.

Plaque with a chinoiserie landscape and gilt details, c. 1680, faience, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Over five chapters, my study explores two interrelated ways these intercontinental entanglements shaped artistic creations in the Dutch Republic. First, I examine the visual materials that emerged from contact between the VOC and Chinese communities, as the Dutch grappled with the problem of visualizing an unfamiliar Other. While existing studies rightly identify the imperial government in Beijing as the more powerful party in an asymmetrical relationship with the VOC, contacts with the court constituted only one part of Sino-Dutch exchanges. VOC personnel had more extensive interactions with other groups of Chinese people, including regional officials, merchants, and the Chinese migrants who populated the Dutch colonial settlement in Batavia, now Jakarta. The first part of my book investigates how the power dynamic between the VOC and each of these entities generated a range of crafted objects, which both informed and were shaped by a multilayered and often conflicted characterization of China in the Dutch homeland.

The second major focus of my project is the exchange of luxury commodities between the Dutch Republic and China. The influx of imports like porcelain and lacquerware drove Dutch producers to create local alternatives, but that does not mean that artistic ideas traveled only in one direction. The VOC transmitted information about Dutch preferences to China, where artists were adept at tailoring their export goods to foreign specifications. Their already customized products would be received as examples of exotic artifacts in the Dutch homeland, where they would inspire emulation by local artists. These Dutch imitations—in the form of drawings, prints, or actual pieces—were sent as models to China, thus creating a perpetual cycle of cross-cultural imitation and innovation.

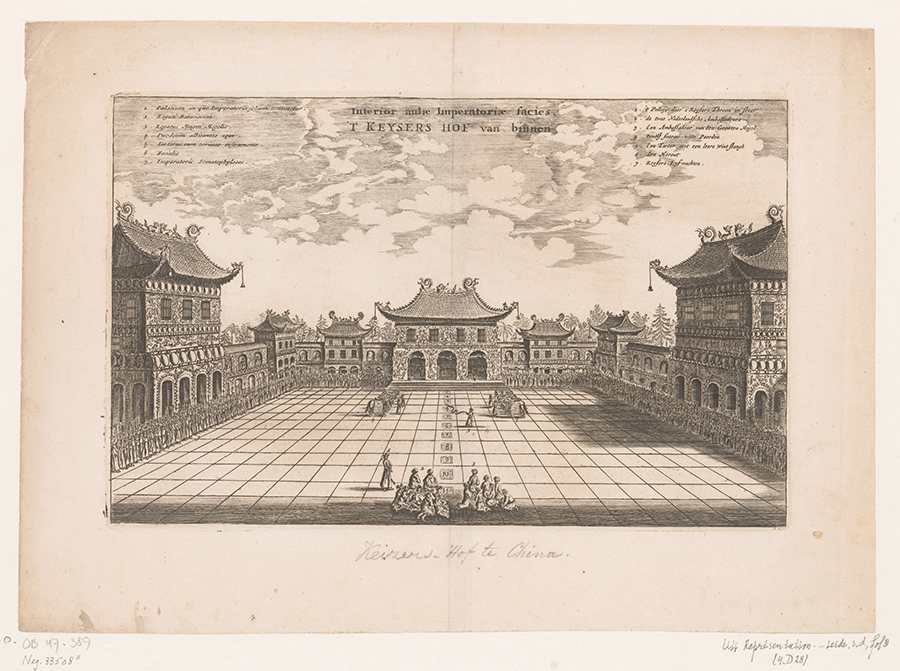

After Johan Nieuhof, “’t Keysers hof van binnen,” engraving in Johan Nieuhof, Het gezandtschap der Neêrlandtsche Oost-Indische Compagnie aan den grooten Tartarischen Cham, den tegenwoordigen keizer van China… (Amsterdam, 1693), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

During my residency at the Center, I worked on Chapters 2 and 5 of the book manuscript. The former explores visual materials created by Dutch artists in the wake of the VOC’s embassies to Beijing in 1655 and 1666. I examine how the images, even those that claimed to be made from life by an eyewitness, relied on European conventions to convey concepts of imperial grandeur to a domestic audience. To signal the foreignness of the scenes, artists added visual markers of exoticism to the familiar framework. My research suggests that elements that were most alien to European customs, such as polytheistic worship and folk entertainment, migrated from printed books to other media, including furniture and ceramics. Decontextualized from the narratives of the embassies, those motifs helped construct an exoticized image of Chinese culture in the European imagination. Chapter 5 addresses the reciprocal imitation and collaborative practices between Chinese and Dutch artists. I analyze how the resulting works, such as blank porcelain pieces made in China and decorated in a Japanese style in Delft, represented the creators’ experimentation and responses to feedback in a changing global market.

As products of the circulation of technological and artistic ideas between cultures, the objects analyzed in my book demand a reflection on broader methodological issues. The global turn in art history has compelled scholars to find a new analytical language, one that could be used to destabilize traditional narratives that were constructed around insular nation-states. Given this concern, I wish to address two questions: Is there room for the traditional quest for origins in the study of transcultural objects? And how might historians of early modern art draw on concepts developed in postcolonial studies in a responsible and productive way? I am grateful to Center members for generously sharing their expertise on these questions, which has been invaluable as I continue to work on my book project.

George Mason University

Samuel H. Kress Senior Fellow, 2022–2023

Angela Ho will return to her position as associate professor of art history at George Mason University in the fall semester of 2023.