In the last four decades, there has been increasing interest in Nubia, which has shed considerable light on the complex interrelationship of Egyptian and Nubian cultures. Some of this research has taken the form of museum exhibitions, which represent a multitude of perspectives. Some have adopted a “continental” view, for example, situating ancient Egyptian or Nubian art within the body of African art in general (Africa in Antiquity, 1978; Africa: The Art of a Continent, 1995; Egypt in Africa, 1996; more recently, The African Origin of Civilization, 2022: a clear nod to Cheikh Anta Diop’s work). Others represent a regional/national gaze, focusing on artifacts found within contemporary Sudan (Sudan: Ancient Kingdoms of the Nile, 1996; Sudan: Ancient Treasures, 2004). Others still have centered on the wealth of Nubia, showcasing superb, typically Egyptianizing, masterpieces (Gold and the Gods, 2014; Nubia: Jewels of Ancient Sudan, 2022). A number of exhibitions have also explored political or racial difference (from Egypt), usually focusing on the later eras (Ancient Nubia: Egypt’s Rival in Africa, 1993; Nubia: Land of the Black Pharaohs, 2018; Pharaoh of the Two Lands: The African Story of the Kings of Napata, 2022). Introspective exhibitions that tackle the problematic histories of collections—as, for example, Ancient Nubia Now (2019)—are especially interesting.

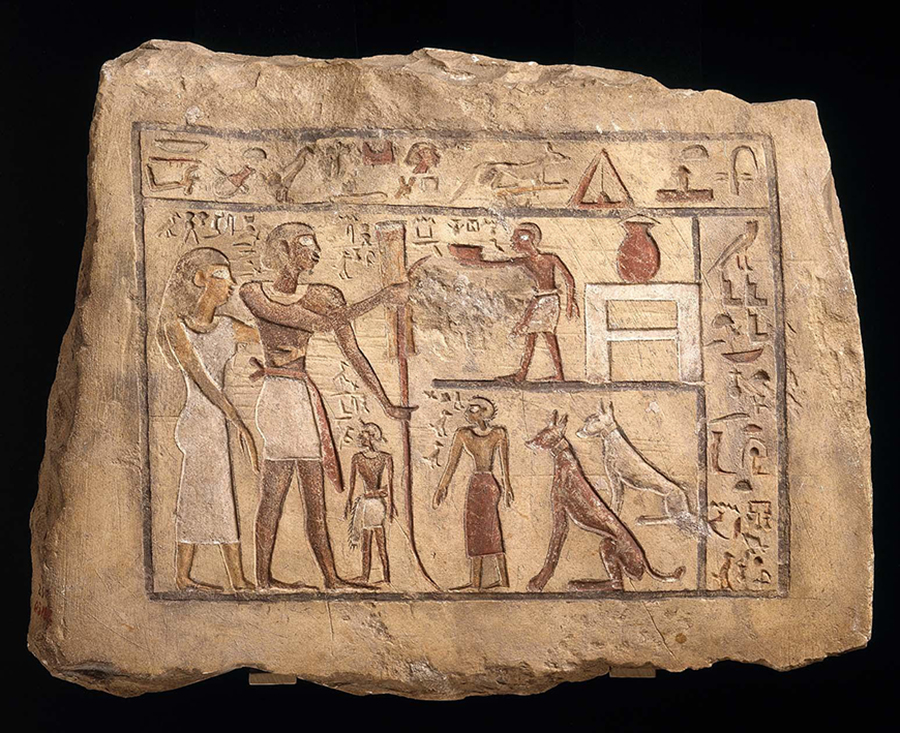

My project centers on a temporary exhibition at the Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia, slated to open in fall 2025. During my tenure at the Center, I compiled a tentative catalog of about 100 artifacts that tell the story of both “Egypt” and “Nubia,” while permitting critical engagement with these terms. The project examines archaeological thinking and evidence to cast light on the intricate and multidirectional rapport among ancient Nilotic cultures in Upper Egypt as well as Lower and Upper Nubia. Beyond merely acknowledging the geographical position of ancient Egypt on the African continent, the exhibition examines the extent to which ancient Egypt was of Africa culturally and the qualities, nuances, settings, and temporalities of that complex embeddedness. It explores the paradigmatic categories of “Nubia” and “Egypt,” what the Egyptian state owes to other African states of its time, and, inversely, what it bequeathed to the latter culturally and politically. In doing so, the exhibition dispels Eurocentric notions of Egypt as the West or the East, while contributing nuance to long-standing inquiries about the interrelationships of ancient Nilotic societies. Further, it demonstrates the liminal qualities of the perceived, rhetorical, and highly politicized “borderland” between Lower Nubia and Egypt, the complex interaction of cultures on either side of this notional limen, and the dynamic interfacing of these ancient civilizations from prehistory through the Kushite and Meroitic areas. More generally, the exhibition highlights the multidirectional interactions of cultures, especially in borderlands. It opens up new vistas on human mobility and assimilation (as seen in the illustrated stela), appropriation and usurpation (as in the Ka statue), colonization and violence, cooperation and trade, the connective tissue between culture and economy, and the manifold links among art, identity, and place.

University of Virginia

Leonard A. Lauder Visiting Senior Fellow, fall 2022

Anastasia Dakouri-Hild returned to the University of Virginia, where she is associate professor of Aegean and Near Eastern art and archaeology. She will finalize her exhibition catalog by summer of 2023.