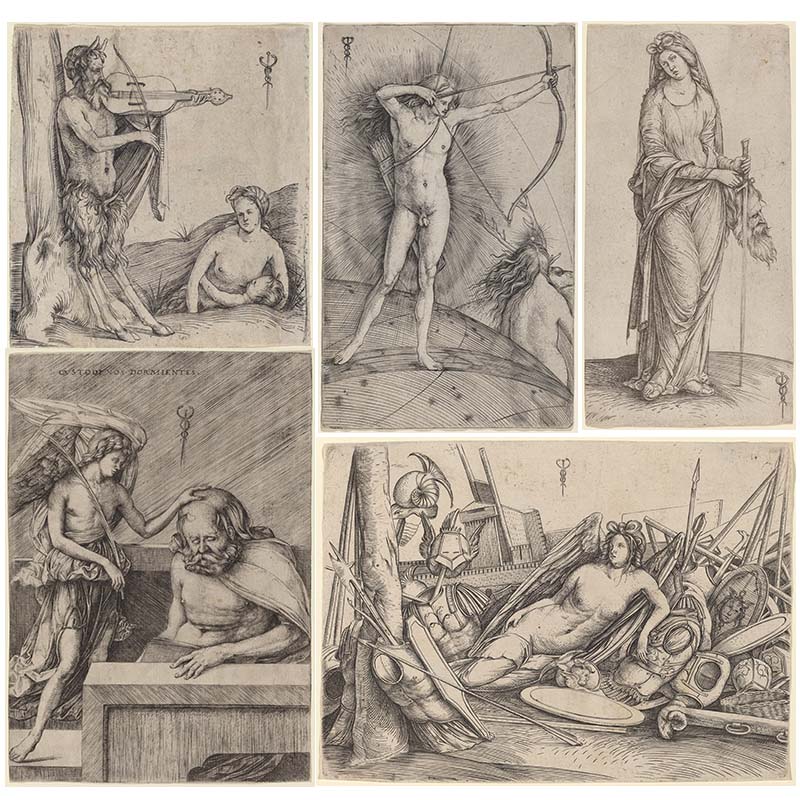

My fellowship at the Center afforded me the remarkable opportunity to consolidate and enhance my scholarly work on the making of the View and further contextualize Jacopo de’ Barbari (c. 1460/1470–1516 or before) as its artist. While there, I made multiple presentations in varying forums that resulted in invaluable exchanges with colleagues at the Center and curators and conservators at the National Gallery of Art. My research has extended earlier scholarship developed for interactive displays first exhibited at Duke University and most recently at the Museo Correr. De’ Barbari, a Venetian artist invited to work north of the Alps by the Holy Roman Emperor in 1500, the year the View was first printed, is a fascinating and exceptional case, and the relationship of the View to his broader oeuvre has demanded greater consideration. Precious time at the National Gallery has advanced my understandings of de’ Barbari’s larger corpus of graphic works through close examination of the museum’s collection of prints. This includes a second-state set of the View, and its analysis has enriched my understandings of the paper, the largest sheets produced in Europe at the time of its first print run. For now, I am publishing my discoveries in the form of two articles: one, examining a selection of de’ Barbari’s engravings, will appear in an edited volume dedicated to Venetian disegno; the second, demonstrating the orchestration of the View’s invention, will be submitted to a scholarly journal. In addition, I have continued to develop a digital repository of de’ Barbari’s prints. This resource holds the potential to cross institutional boundaries—a simple yet effective tool for shareable, in-depth study and engagement. Enhanced visual observation through digital tools has helped me answer unresolved questions about one of the greatest technological and artistic masterpieces of its time. Art-historical methods of the 21st century have thus come together to reveal the richness and originality of the visual inventions of the Renaissance.

Duke University

Ailsa Mellon Bruce Visiting Senior Fellowship, spring 2022

Kristin Love Huffman is a lecturing fellow in the Department of Art, Art History & Visual Studies at Duke University and codirector of Visualizing Venice/Visualizing Cities. Her edited volume, A View of Venice: Portrait of a Renaissance City, is forthcoming with Duke University Press.