Expanding Agency: Women and Modern American Architecture and Design, 1923–1972

The contribution of women to the creation of the built environment has not been totally ignored, but neither has it received the attention it merits. Part of the problem is that historians of architecture have attributed too much agency to architects, rather than paying attention to the other ways in which women have been able to shape architecture and design. “Expanding Agency” documents the impact that women also had as journalists, entrepreneurs, and institution builders, and the degree to which their activities were supported by other women and targeted female consumers. It casts new light on the dissemination of modern architecture and design between 1923, when Ethel Power (1881–1969) became editor of House Beautiful, and 1972, when Learning from Las Vegas, coauthored by Denise Scott Brown (b. 1931), was published. Although my book manuscript focuses on five women—Power, Estrid Ericson (1894–1981), Ethel Bailey Furman (1893–1976), Chloethiel Woodard Smith (1910–1992), and Gira Sarabhai (1923–2021)—during my time at the Center I focused on Power, Furman, and Smith, as the relevant archives for Ericson, the founder of Svenskt Tenn, and Sarabhai, the cofounder of the Calico Museum of Textiles and National Institute of Design, are located in Stockholm and Ahmedabad, respectively.

Writing women into history significantly changes the stories we tell. My survey of House Beautiful, for example, revealed that under Power’s editorship a shelter magazine targeted at women with over 100,000 subscribers introduced its readership to the International Style. Articles on the subject were written by Henry Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson before they had curated their influential exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, which was seen by significantly fewer people. Power also turned to Ise Gropius and Dorothy Todd, the former editor of British Vogue, for articles on the latest developments in Europe. But perhaps more importantly, she consistently hired women to write about the achievements of women architects, landscape architects, designers, and decorators and to instruct women readers in everything from the history of architecture and the decorative arts to the mechanical systems being developed for their own houses. House Beautiful empowered women to be well-informed consumers of architecture and design.

Power wrote for an audience that she presumed to be white, but women from other communities also used architecture to support themselves and their families while furthering the aspirations of their communities. For Furman, who designed houses and churches in and around Richmond, Virginia, her professional activity was almost inseparable from her commitment to Black economic and political advancement. Her meticulous drawings for the 1962 addition to the city’s historic Fourth Baptist Church, of which she was a member, and half a dozen houses for members of the Snead family complemented her civic activism, which included registering Black voters, fundraising for the March of Dimes, and campaigning for a high school to be placed in her historically Black Church Hill neighborhood.

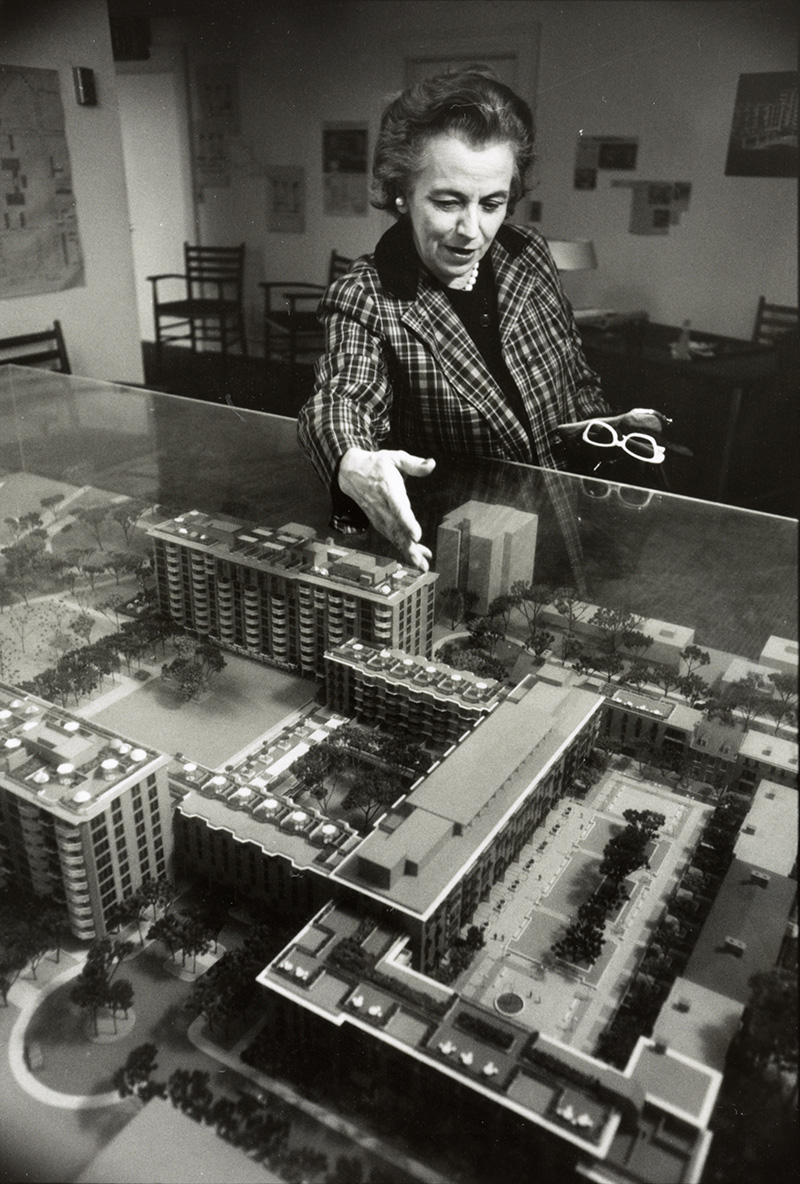

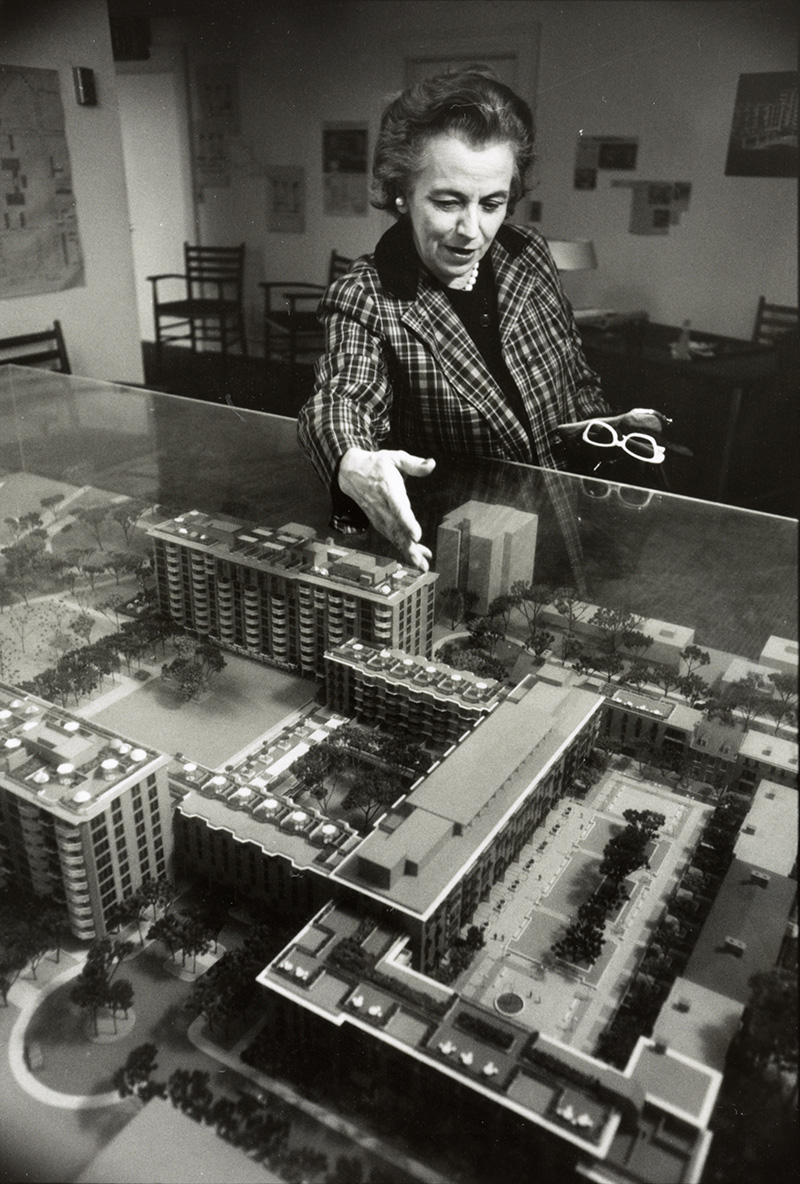

Architect Chloethiel Woodard Smith presenting a model of her Harbour Square project for Southwest Washington, DC, c. 1960, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-31775

Restricted by race, Furman’s networks were local rather than national. By contrast, Smith, who from 1963 to 1983 headed the largest woman-run architectural practice in the United States, was able to depend in part on female journalists, including Jane Jacobs and Betty Friedan, for support. Although she resented being pigeonholed as a “lady” or “woman” architect, Smith’s atypical success depended in part on publicity she received for being an exception; at the time, women made up less than 1 percent of all registered architects in the country. Such attention, which focused on her ability to erect integrated middle-income housing, typically on sites cleared for urban renewal, more often took the form of newspaper and magazine articles than notice from the architectural press or the profession. However Smith also made effective use of presidential appointments, including to Washington’s Commission of Fine Arts, to help shape the city of which she was a longtime resident. It was, for instance, her idea to locate what became the National Building Museum in the former Pension Building.

The careers of Power, Furman, and Smith demonstrate that women’s engagement in shaping the built environment was not simply a matter of designing and commissioning buildings or of a commitment to specific styles. Deeply intertwined in the gender and racially constituted communities to which they belonged, these women were more often motivated by a desire to empower others, whether by providing them with better places to live or with the tools to help them achieve that for themselves.

University College Dublin

Ailsa Mellon Bruce Senior Fellow, 2021–2022

Kathleen James-Chakraborty will return to her position as professor of art history at University College Dublin in Ireland. She will continue her current research as a holder of a European Research Council Advanced Grant (2021–2026).