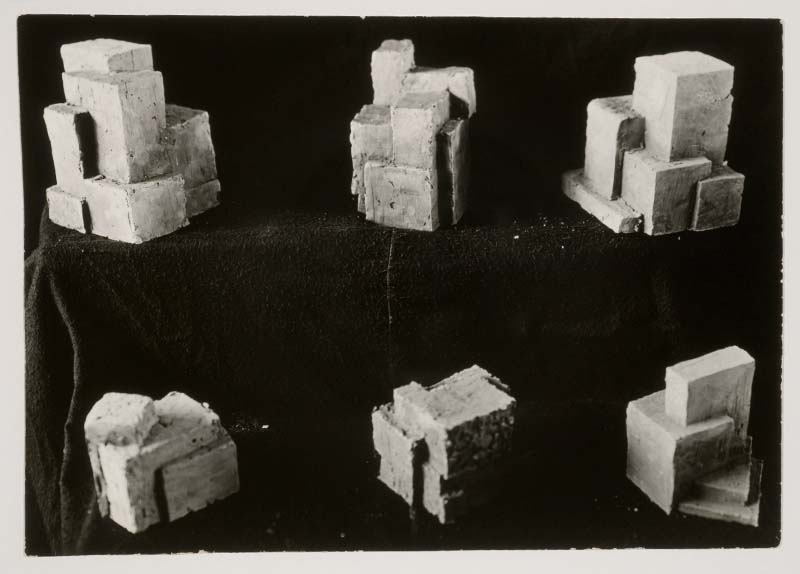

While at the Center, I have concentrated on completing the first and last of the book’s six chapters. Chapter 1, “Model Utopia,” explores the indeterminate scale and temporality of early Soviet models in the first decade after the October Revolution, the era of constructivism; it attends to works by such luminaries as Moisei Ginzburg (1892–1946), Liubov Popova (1889–1924), and Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953), as well as models made by students at VKhUTEMAS (Higher Art and Technical Studios), the school of art, architecture, and design founded in Moscow in 1920. Situating the work of famous figures and anonymously produced images in relation to the Soviet experience of modernization, the book’s four central chapters—“Monumental Snapshots,” “Under Construction,” “Time Machines,” and “Happy Model Childhood”—all take place in Moscow between the start of the first Five-Year Plan in 1928 and the beginning of World War II. Chapter 6, the book’s final chapter, is set at the Soviet Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair in 1939 and addresses the carefully produced images of the model for the long-planned but never built Palace of Soviets by Boris Iofan (1891–1976), which encouraged an American audience to believe the building already existed. Addressing architecture, the visual arts, science fiction, photography, and film, “Model Soviets” reveals how models and their images engaged visual scale, shifting notions of Soviet temporality, and an evolving “factographic” aesthetic to present utopian visions as monumental facts even as the Soviet Union itself remained chaotically under construction.

Scripps College

Ailsa Mellon Bruce Senior Fellow, 2021–2022

In 2022–2023, Juliet Koss will be a fellow at the Harriman Institute for Russian, Eurasian, and East European studies at Columbia University. She will return in fall 2023 to Scripps College in Claremont, California, where she is professor of art history, Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Chair in the History of Architecture and Art, and chair of the Department of Art History.