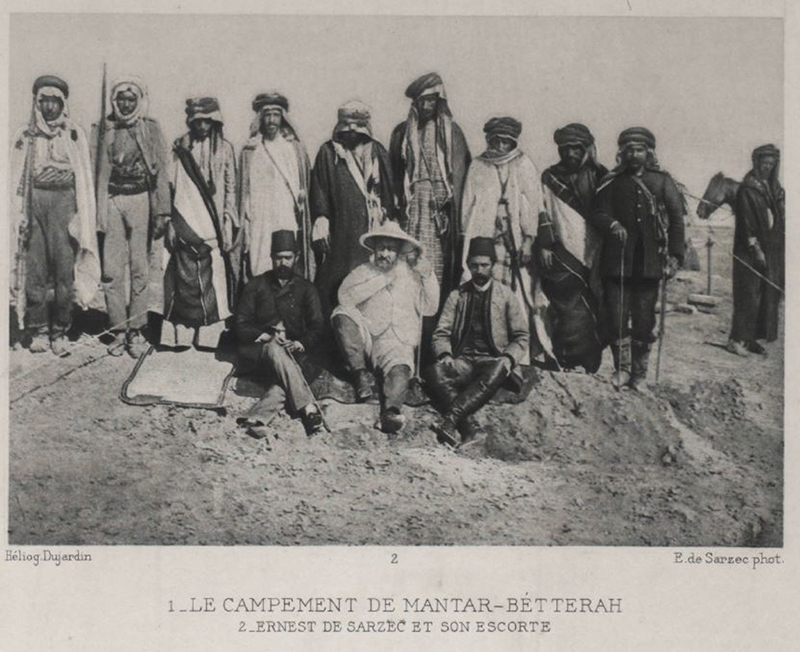

In circa 2400 BCE, Enmetena, the ruler of Lagash in southern Mesopotamia, ordered the fashioning of a vase to be dedicated to his chief god Ningirsu, the god of war and agriculture. Mounted on a copper stand, the gleaming body of the vase was masterfully hammered from a single sheet of silver and engraved in two registers with couchant calves above a series of heraldic compositions featuring the lion-headed Imdugud bird, Ningirsu’s symbol. It was appreciated in its own time as an exquisite work, as evidenced by the ekphrastic inscription wrapped around its mouth, referring to its “refined silver.” Further, the placement of this text mirrored the performative function it had to fulfill: we are told that the god Ningirsu consumed monthly fat offerings, of the kind derived from the depicted calves, through the mouth of this vase. During every performance, text and image worked together for the proper execution of the ritual, upon which the well-being of the ruler Enmetena, and by extension the lands he ruled, depended. The vase was excavated in 1888 by a team led by the French vice-consul in Basra, Ernest de Sarzec, and sent to the Imperial Museum in Istanbul as the 1884 Ottoman Antiquities Law claimed absolute ownership of all excavated material. In clear violation of this regulation, however, Sultan Abdülhamid II presented the vase in 1896 as his personal gift to the Musée du Louvre. Today, it is one of the most celebrated pieces in the Near Eastern collection of the Louvre.

The case of the silver vase of Enmetena nicely encapsulates the main threads that have informed my project, namely an engagement with multiple modes of temporality and materiality. My study material has been the archaeological site where this vase was excavated: modern Tello (ancient Girsu) in southern Iraq. Its excavation marked the “discovery” of the Sumerians and triggered an archaeological sensation in 19th-century Europe. I have brought the art history of this ancient site into the present by constructing what I call a “site-world”: the totality of multi-temporal networks of material encounters, discussed not in isolation but as embedded in an understanding of the mutual constitution of past and present, and of object and subject. This site-world not only encompassed the physical site of Tello and its material remains, but also the variety of discourses that continue to grow out of them. Consequently, my research has bridged traditional disciplinary divides by placing the processes of creating and viewing artworks in the third millennium BCE on equal footing with reception processes across millennia. Similarly, my stylistic and iconographical analysis of artworks has been accompanied by critical readings of both Sumerian texts and late Ottoman documents about their production, excavation, transportation, and exhibition.