Anna Aline Mehlman Dumont

From Design Reform to Fascist Craft: Textiles and Italian Women’s Labor, 1870–1945

Who is the author of a textile? The 1923 fabric appliqué Rosetta ai telaio by futurists Fortunato Depero and Rosetta Amadori subverts what are often assumed to be the dynamics of artistic production. It shows, in bright patches of blocky colored felt, Amadori, seated at an ample frame on which she is stitching a large cloth—perhaps the very appliqué in question. Designed by Depero but almost certainly sewn solely by Amadori in the craft workshop (casa d’arte) they shared, it is both a self-portrait, in which Amadori has stitched an image of her own laboring hands, and a portrait, in which Depero has laid bare the very working dynamics that throw his own authorship in doubt. Rather than hiding this shared labor and relying on the authoritative mark of his signature, which Amadori has affixed to the bottom of the work in bright orange felt, their shared labor is the very subject of Rosetta ai telaio.

Such works demand a reassessment of how modern artistic authorship was constructed. While historiographic narratives often construe feminine-gendered artistic work as hidden, my research demonstrates its remarkable visibility in the first decades of industrialization in Italy. As fabric moved from craft into art, taken up by the Italian avant-garde as the futurists sought to disrupt the bourgeois hierarchies of the arts, fine art was reconstituted in productive tension with the idea of craft. Simultaneously, artists, theorists, and entrepreneurs remained invested in defining textile production as an artisanal tradition, even as textiles were increasingly positioned as key to Italian industrial modernity.

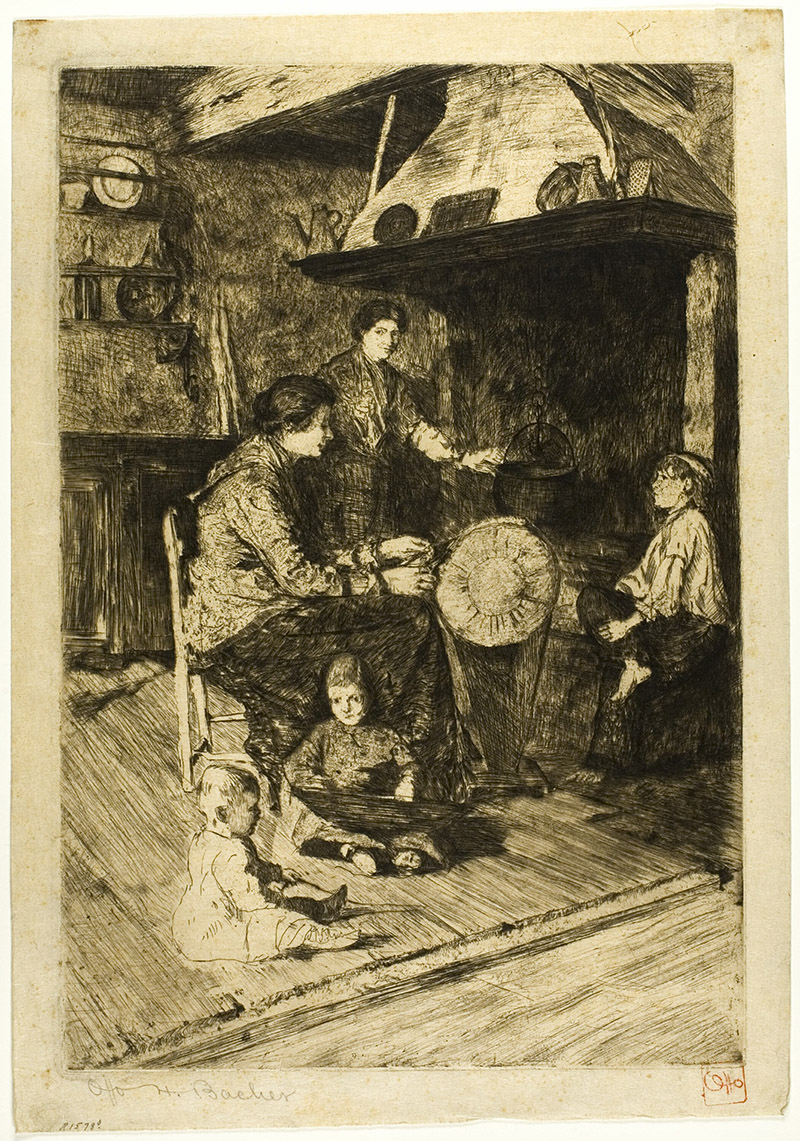

Otto Henry Bacher, The Lace Maker, 1880–1882, etching in black on cream laid paper, The Art Institute of Chicago, The Charles Deering Collection, 1927.2143

Yet while everyone from art critics to government officials turned their attention to the aesthetic and social potential of practices from lace-making to carpet-knotting, to the industrial production of synthetic fibers, contemporary observers demonstrated a remarkable uncertainty about what to make of the women actually doing this work. In 1902 the critic Mario Morasso puzzled, “The manufacture of lace is considered by some to be an art, by others an industry; both are wrong and both are right, since it is simultaneously each and both, or rather it has two faces.” In the struggle of observers to categorize this labor as art, craft, domestic work, and industry, these types are revealed to be less a question of specific practices and more a product of the social and economic systems in which the women found themselves. An 1880 print by the American artist Otto Henry Bacher, for example, shows a lace-maker plying her trade from home. Her children sit blank-faced, implying the industrial alienation such arrangements brought into private homes. Such elisions had substantial effects on the lives of female workers, governing their claims to the political identities that offered male workers forms of revolutionary collectivity.

My dissertation begins with the post-unification upheavals of the 1870s and continues through the rise and fall of the Fascist regime. Drawing on exhibition catalogs, photographs, craft education manuals, workshop daybooks, trade newspapers, government documents, and letters, I identify increasingly rigid rhetorical divisions among modernist art, design, and older styles of ornament. Whereas the late 19th-century lace revival was pitched as a nationalist initiative for the benefit of female workers, by the Fascist period textile work came to be seem as a service to the nation, one in which women’s benefit from their labor was expected to come second to national glory. In the course of these shifts, individual male designers were privileged at the expense of more collective workshop models rooted in histories of Italian small industry. As a result, women workers were displaced from the public sphere, and from claims to authorship of crafted objects within modern art and design.

Travel in the Veneto, Genoa, and Rome during my fellowship term allowed me to trace the history of these changes from an “internal” standpoint, searching for evidence of how they were experienced by women workers. For example, I unearthed a 1908 defamation lawsuit launched by the biggest lace-making company on Burano against the local socialist newspaper in retaliation for publishing a report on the desperate living conditions of the lace-makers. I visited the planned synthetic-textile-producing town of Torviscosa, built in the 1930s to process cane grown in the swamps of Friuli into cheap fabric, where a workers’ revolt delivered a blow to Fascist wartime industry. Focusing on such long-ignored episodes in the history of female makers, my work reveals the category of fine art to be a contingent product of specific, and gendered, historical exigencies and deepens our field’s understanding of how and why it came to be so.

Northwestern University

Twelve-Month Chester Dale Fellow, 2021–2022

Following her Center fellowship, Anna Aline Mehlman Dumont will begin an Andrew W. Mellon Chicago Objects Study Initiative Curatorial Fellowship in the textiles department at the Art Institute of Chicago.