Western academies of art, before the proliferation of photography in the later 19th century, were historically the single most important authority for the social construction of the visual field. Academies were not simply for the training of techniques; they were disciplinary institutions that instructed students in how to properly represent the world according to the needs of patrons, elites, and, later, wider markets. The rapid multiplying of academies of art—almost 100 in 18th-century Europe alone—manifested an epistemic shift toward the institutionalization of the training and production of artists.

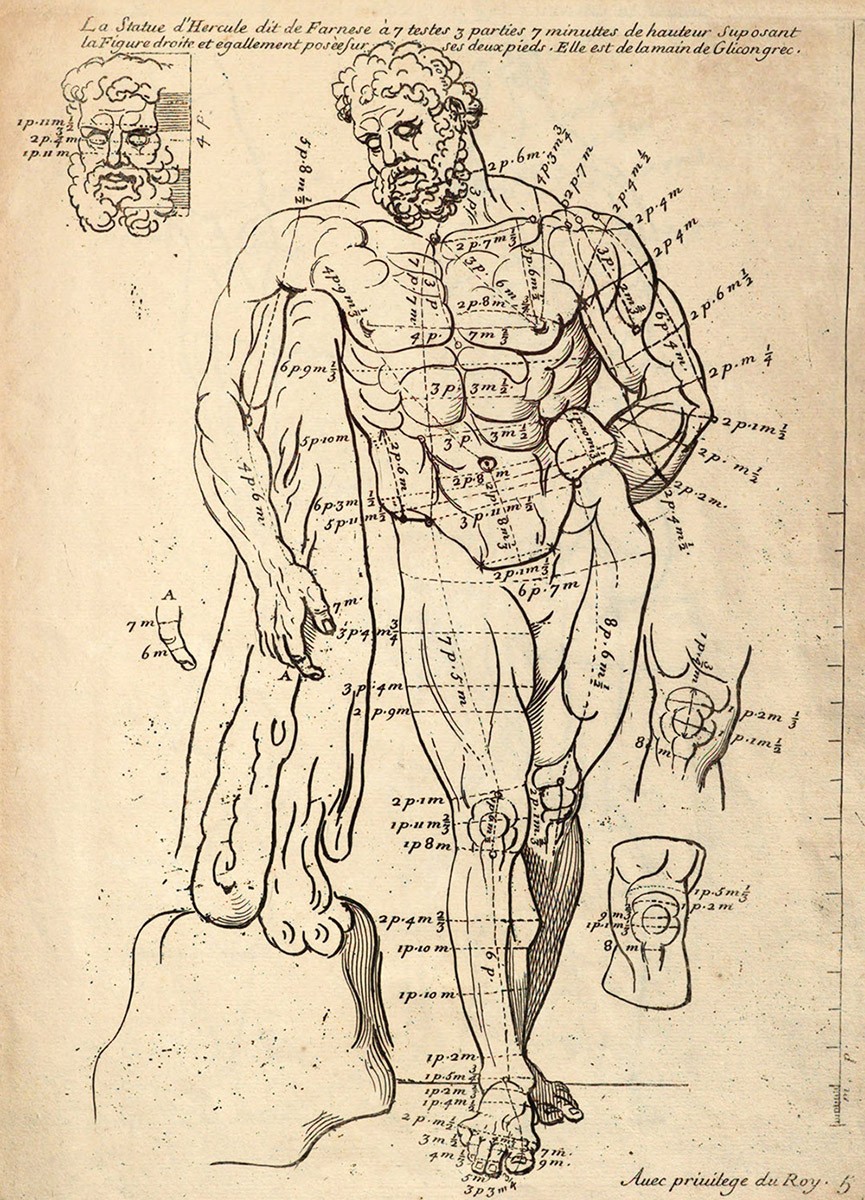

European-structured academies were replicated not only within nations but across international borders including those of Latin America. Like their European counterparts, academies in Latin America must be understood as the application of an orderly, Enlightenment-era apparatus linked to the demands of managing increasing numbers of students, producing artists through a centralized system of instruction based on visual copying, with an eye toward normalizing the human body. The human body was placed—both literally in terms of space and figuratively in terms of power—at the center of the curriculum. Accordingly, there was a direct relationship among the material infrastructure of academies, the studio pedagogy of artists trained to represent the human figure, and the performance of elite power. In my book, I examine copying not only on the material level of creating an ideal human figure on paper, but also copying in terms of its various cognates of emulation, replication, reproduction, mimicry, and reification at an institutional level.

The standardization of training did not, however, preclude expressive or formal differences in students’ artwork, or the teachers’ resistance to regulations. My book project reveals previously unexamined critical differences, as expressed in both the formal construction and political uses of the body, among several Latin American academies of art placed in dialogue with their European models.