Melanee C. Harvey

Patterns of Permanence: African Methodist Episcopal Architecture and Visual Culture

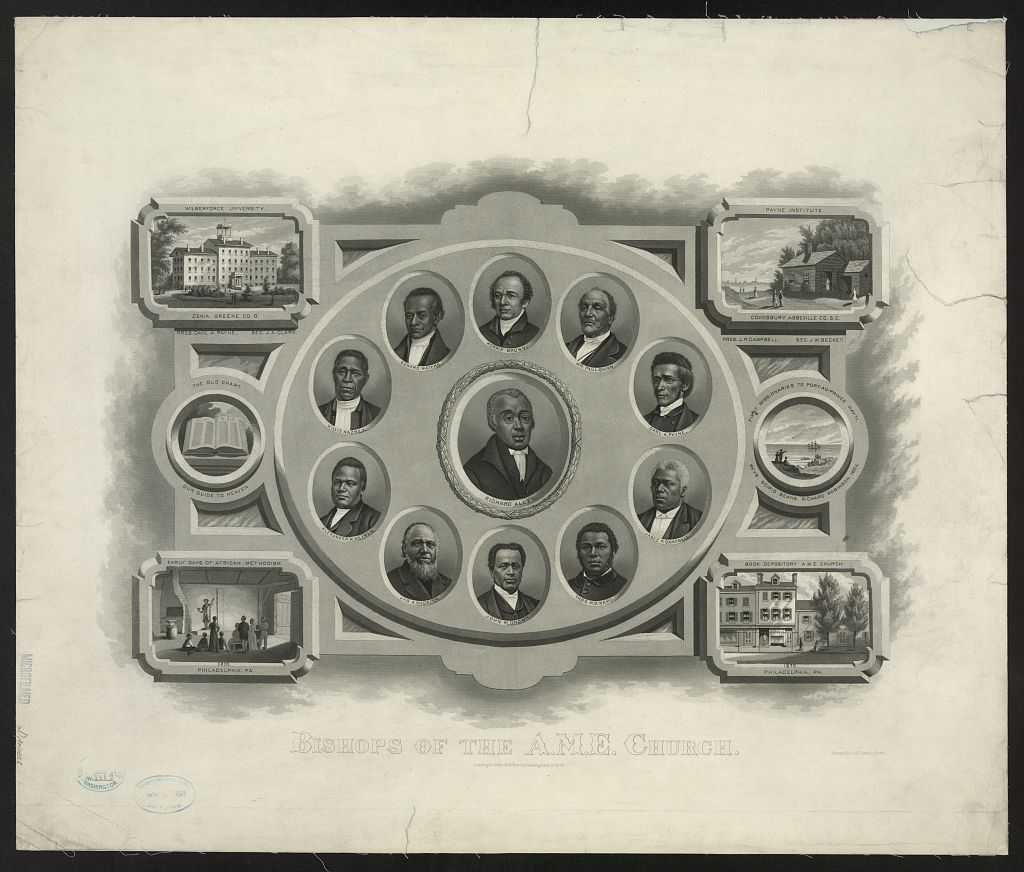

Bishops of the A.M.E. Church, c. 1876, lithograph, printed by J. H. Daniels, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The African Methodist Episcopal (AME) denomination is the oldest independent African American religious institution, developing from a retrofitted blacksmith shop in late 18th-century Philadelphia into a national network of religious communities across the nation by the late 19th century. The book manuscript I have advanced during my residency at the Center is the first extensive analysis of the architectural and artistic traditions that were promoted across AME sanctuaries, homes, and educational institutions. Tracing such underappreciated cultural histories illuminates the active role that AME members played in promoting aesthetic discourse and art patronage across individual and communal initiatives. Crafting and circulating images of the denomination across portraiture and architectural views, this religious community made intentional decisions about the style, content, and context of the structures they erected and the art that would adorn their walls.

As noted in James A. Porter’s Modern Negro Art (1943), Bishop Richard Allen (1760–1831), founder of the AME denomination, established a legacy of art patronage during the late 18th century by commissioning a pastel portrait to commemorate his attendance at the Christmas Conference, which marked the founding of American Methodism. During my residency, I enhanced my argument concerning the differences between portraits produced during Bishop Allen’s lifetime and those printed posthumously. Further research revealed additional examples of the AME denomination shaping the visuality of their founder by commissioning revisionist portraits for the 1876 Centennial Exposition and for denominational publications in the 1890s. Moving beyond a singular focus on Bishop Allen, I expanded this chapter to consider the role of women in the visual history of the founding era of African Methodism, which I extend from the late 18th century to the Civil War. Portraits of early AME clergy and members—such as an engraving of lay preacher Jarena Lee (1783–1864) and a photograph of Priscilla Baltimore (1801–1882), who founded two congregations—signal an expansive visual record of women who led church-building initiatives. This extensive tradition of women’s labor for African Methodism has been minimized in patriarchal historical accounts of the denomination.

My research and writing while in residence moved to the second chapter, which considers the role of art collections and art education at Wilberforce University in Ohio, the educational center of AME in the 19th century and one of the oldest historically Black universities in the nation. Art education and the development of an art collection supported ideologies of domesticity and uplift that undergirded the cultural practice of Black Formalism. The visual arts complemented Wilberforce University’s strong classics curriculum, which stood apart from the industrial programs at the Hampton Institute and Tuskegee Institute. Under the auspices of the AME denomination, Wilberforce University served as an anchor in the national geography of African Methodism, attracting Black men and women to exercise self-determination through educational pursuit, which required both geographic and social mobility. By mining 19th-century African American newspapers and biographies, I identified art practitioners and photographers at Wilberforce during the late 1870s and 1880s, crafting an account of the university’s function as an early repository for visual arts and material culture.

I also succeeded in transforming the third chapter on the architectural traditions of the AME denomination from a comparative study of three urban cathedrals to a broader analysis of urban building practices. Although previously explored examples, such as Metropolitan AME Church (1881–1886) in Washington, DC, represent East Coast patterns in style and local materials, this chapter now charts the structural expansion of the denomination in the southern region and along the expanding western frontier. In the decades after the Civil War, AME congregations across these regions architecturally evolved from wood-frame structures to monumental brick revival-style edifices, creating a network of cultural sanctuaries that nurtured African American philosophy, religious beliefs, and cultural uplift. Photographs of late 19th-century southern churches, such as Big Bethel AME Church in Atlanta and Steward Chapel AME Church in Macon, both in Georgia, were circulated and collected through the early 20th century as a means of conveying safety and perseverance. These images also communicated the political and socioeconomic mobilization of African Americans who directly opposed Jim Crow segregation and institutional practices of white supremacy.

Howard University

Paul Mellon Guest Scholar, 2020–2021

Melanee C. Harvey will return to her position as assistant professor in the Department of Art at Howard University. She will continue to advance museum studies initiatives for the department while serving as art history coordinator and committee chair of the James A. Porter Colloquium on African American Art and Art of the African Diaspora.